Thousands of men have flocked to rallies led by the Promise Keepers, a religious organization that aims to restore male authority and make men better husbands and fathers. But what price will women pay?

Originally published in New Woman.

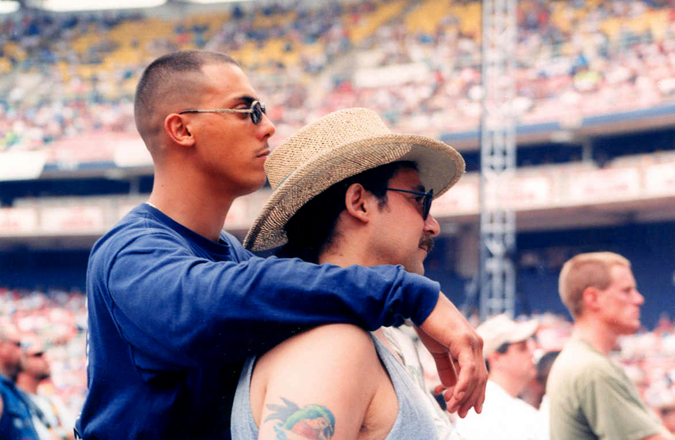

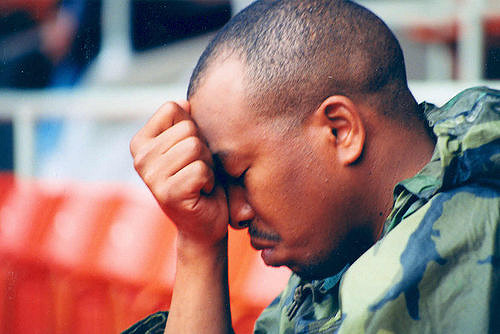

Promise Keepers rally. RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C., 1997. Photo by Elvert Barnes Protest Photography. All photos are published under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

SITTING ON THE FLOOR OF THE SILVERDOME in Pontiac, Michigan, it’s hard not to fixate on the overhead billboard of the Marlboro Man. Rugged and silent, he brandishes a lasso with one hand while a cigarette dangles from his stoic lips. Even for those of us who have never smoked, he has become an archetype of American manhood, this cowboy who takes care of himself, needs no one but his horse, and keeps his emotions locked away.

But today, on a rainy spring morning, someone has unfurled a banner under the Marlboro Man with the hand-lettered words TOUCH MY LIPS WITH HOLY FIRE. With the football season months away, the Silverdome has been taken over by the Promise Keepers, an all-male organization that packs arenas across the country with tearful, prayerful, evangelical Christians. Fifty-seven thousand men of all ages have descended on Pontiac for the weekend-long revival—men with baseball caps, ponytails, leather jackets, spiked haircuts, wheelchairs, earrings, and every type of Christian T-shirt imaginable. They’re comparing fishing photos in the bleachers, playing Hacky Sack on the floor, but mostly they’re worshiping together and hugging one another like they never do at home. And, almost as if to defy the hypermasculine cigarette ad above, they’re singing from their hearts, arms lifted skyward in submission to God: More like you/Jesus, more like you/Touch my lips with holy fire/And make me more like you.

Since its founding in 1990 by then University of Colorado football coach Bill McCartney, Promise Keepers has blossomed into one of the fastest growing phenomena in American religion today—a $90-million-a-year organization with 450 employees and worldwide expansion plans. Last year, more than a million men, most from conservative Protestant churches, filled stadiums from San Diego to Syracuse for 22 “conferences,” or rallies. This year’s conferences are preludes to PK’s biggest event yet, a “sacred assembly” on the Mall in Washington, D.C., October 4, which organizers hope will draw upwards of a million men.

Promise Keepers calls for the ultimate family value: a recommitment by Christian men to marriage and fatherhood. According to PK, men have abdicated their responsibilities in their homes and communities, dumping the leadership burden on women. As family men, some have been dictatorial, others neglectful. (McCartney himself says he realized, when he founded the Promise Keepers, how much he had neglected his wife during his coaching career.) They’ve abandoned the church. And they’ve become slaves to workaholism, pornography, adultery, and racism. PK encourages men to give up these vices with the help of God and the friendship of other men.

PK boasts that the message is sinking in, and that men return from rallies as more nurturing husbands and fathers. “It would blow your mind,” says Holly Faith Phillips, the wife of PK president Randy Phillips. “We received a letter from a woman who said that her husband went away a frog and came back a prince. She wrote, ‘I don’t know where my husband is, but you can keep him, because the guy who came home is a better man.'”

But Promise Keepers’ detractors say that under that gentle exterior lies a mass movement of men who want to beat back the political advances that women have made over the past quarter century. The evidence: PK’s leaders and speakers often interpret the Bible to mean that men are created in God’s image and thus charged with leading their households. Men are expected to submit to the will of God—and women are expected to submit to the will of their husbands.

Promise Keepers rally. RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C., 1997. Photo by Elvert Barnes Protest Photography.

PK counters that it’s not talking about authoritarian rule. “Any man worth his salt knows that the best way to get respect is to give respect,” says Holly Phillips. But, in the final analysis, she says, God has anointed men alone to lead their families. “From a Biblical perspective, there is somebody for whom the buck stops there,” she explains. “In the family unit, the buck stops at the man. Does that mean he has the right to lord over his kids and his wife? No. [My husband] asks for my input. He asks for my insight. And then he makes the decision and I support him. That’s an awesome responsibility. I wouldn’t want to be in his shoes if you paid me.”

That’s a troublesome idea—for many Christians and non-Christians alike. “In some way, the Promise Keepers are saying the same thing feminists have said about men’s involvement in the home,” says Carol Adams, coeditor of Violence Against Women and Children—Christian Theological Sourcebook. “The pressures on the family in the United States today are intense. To have a man who’s been absent from the home come in and be involved is a good thing. But the language and perspective imposed on his reinvolvement are disturbing. It’s as if the only way for men to get involved is to have this authoritarian role.”

Several feminists I interviewed worry that giving men this absolute power to lead their families might tempt some to abuse it. While no one can offer any hard statistics about the effect of PK on domestic violence, Jackie Hudson, a counselor in Eugene, Oregon, estimates that 70 percent of the batterers who come through her treatment center have attended PK rallies. The question is whether PK’s heady words about male authority somehow inspired them to be abusive, or whether PK made these men realize that their violent tendencies were wrong.

Some critics also question whether Promise Keepers is an underhanded attempt to create a new power base for conservative heterosexual men. McCartney, PK’s founder, is famous in Colorado for crusading against abortion and gay rights, and his ministry has been endorsed by Christian Right leaders like Pat Robertson and James Dobson. Although PK calls its agenda non-political, it has denounced abortion and homosexuality. Russ Bellant, a Detroit author who has written extensively about the religious right, says the ministry’s message ought to alarm anyone who believes in sexual equality. “Promise Keepers may be the strongest, most organized effort to capitalize on male backlash in the country during the nineties,” he says.

Talking to supporters and critics, it was hard to reconcile those two visions of this burgeoning religious movement. Does Promise Keepers produce Christians who return to their families with a renewed spirit of love and respect? Or does it promote and reinforce male supremacy? There was only one way to find out: fork over $60 for the yellow wristband that would grant me admission into the Silverdome.

THE PODIUM IS ADORNED to look vaguely like an ancient temple: white columns ascending heavenward like Jacob’s Ladder, flanking a backdrop painted like oversized bricks. A stylized illustration of a “Godly man,” his body trisected into Black, white, and Native American, reminds us of the urgency of bringing men of all races into the body of Christ. Indeed, while whites dominate the crowd, more than half of the speakers are African American.

The first night, we sing. Oh Lord, we sing. A smiling, young worship leader with a teen-idol face has us on our feet, belting out songs with Pentecostal ecstasy. Guitars, drums, and electric keyboards keep us in tune. As the evening wears on, men start touching their neighbors’ shoulders—tentatively, awkwardly—waiting for the cathartic moment when they can shed the machismo and be themselves.

Promise Keepers rally. RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C., 1997. Photo by Elvert Barnes Protest Photography.

That moment comes when Bruce Wilkinson takes the stage. The founder of Atlanta’s Walk Thru The Bible Ministries, Wilkinson has an urgent message to share: October is coming up quickly, and with it, the massive Promise Keepers gathering in Washington. If everything goes as planned, “the whole nation will fall on its knee and God will have to bring revival.” But even though “men are praying more than ever,” he says, they still haven’t turned away from their major weakness—the defect that he claims plagues Christian men “five hundred percent more” than any other. “What’s your sin?” he asks us. “Where is the shame in your life?” No one answers for a moment. Then, like little flashbulbs popping, men call out: Lust. Lust. Lust. “That’s right,” Wilkinson says. “It’s lust. It’s pornography. It’s adultery. It’s fornication. It’s homosexuality. Until the men in this room decide it’s enough and to end it, Heaven is going to start closing its ears and will not send revival.”

One of the most dramatic spectacles of a Promise Keepers conference comes when an arena full of men repent together, and tonight Wilkinson wants every man who has committed a carnal sin of any nature to humble himself before God. “If you know you have sexual immorality in your life,” he says, “tonight is the night it’s going to end. When you go home, you fix it so you can’t do it anymore.

“Well, men, this is the moment of destiny right here. Lord help us. If you are a sexually immoral believer, then come forward right now and kneel right here.” First dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of men pour forward, clogging the aisles. I grab a notepad and try to make my way forward, but a heavyset man intercepts me and throws two big arms around me. “I’ve just got to confess this,” he says, not noticing I’m a reporter. “Homosexual tendencies, adult bookstores, pornography. I’m so ashamed. This has got to stop. Say a prayer for me.”

Beside me, a 20-year-old machinist named Darrin Speck, with blue eyes and high cheekbones, has confessed a laundry list of sins to one of his hometown buddies. Though he has never had sex, he has watched pornographic videos, and the images have lingered. “You have that naked woman in your head,” he explains to me later. “It don’t matter where you go; it’s in your head. You have these lustful thoughts, and it makes you feel so dirty.” Speck and his friend hold on tight, weeping—and when the tears subside, he turns to me and throws his arms open wide. “Love you, brother,” he says.

I want to love Speck back, despite the message coming from the podium, which condemns masturbation and homosexuality with the same force it condemns adultery. What I do love is his ready affection, a rare commodity in American men. So I give into his hug. And as the rest of the Silverdome serenades the sinners in the aisles, Speck and I stand in a side-by-side embrace, letting the music wash over us. “I feel so free,” he says.

Later, Speck tells me that at last year’s conference, he had an equally tearful confrontation with his own racism. “I was never a neo-Nazi skinhead, but I had the idea that I’m not going to associate with [Blacks], that we’re more supreme,” he tells me. Then a preacher talked about the oneness of all men in Christ. “I remember he called on us to make reconciliation with any race you’ve felt prejudiced toward,” he says. “At that moment, I just knew in my heart that I’ve had these prejudiced feelings against Black people, and I can’t live like this and be an effective Christian.

Promise Keepers rally. RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C., 1997. Photo by Elvert Barnes Protest Photography.

“A few rows in front of me there were a couple of Black guys. So I walked over to them and I embraced them. I said, ‘I need to confess. I’ve showed hate toward you before. Not you in particular, but I’ve showed hate toward your race. And I want to ask you for forgiveness.’ I’ll never forget seeing these two guys. They were also tear-filled. And they said, ‘Brother, we forgive you.’ They said, ‘We understand. But that’s behind you now. We’re brothers in Christ. We’re going to see you in Heaven together.'”

Redemption doesn’t come in a single night, and part of the Promise Keepers’ plan is to keep men accountable to their buddies throughout their lives. Saturday morning, a minister named Rod Cooper urges us to build lifelong friendships with one another, relationships so close that we can confess our addictions and weaknesses, knowing we’ll receive unconditional love in return.

“Every man needs a huddle,” says Cooper, the former chaplain for the Houston Oilers football team. “If a man is going to survive—no, if he’s going to win—in the battles of life, he’s got to have a huddle of good men around him to cheer him on and bandage his wounds. If the son of God felt it was necessary to have a huddle of men in his life, what makes you think that you and I are exempt?” He recounts the story of a soldier who risked his life on the battlefield just to sit next to his dying friend, and eyes all around me start misting over.

When the sermon draws to a close, Cooper tells us to form huddles of our own. I join the three brothers sitting beside me—blond Midwestern men in their 30s. We hold hands and someone prays. After the last amens, one of the guys—David Everitt, a bearded man who runs a trailer-park maintenance shop—burrows his head into his brother’s shoulder and breaks into long, racking sobs.

When he comes up for air, Everitt seems shaken by the battlefield story. “I can’t comprehend that. I haven’t had a friendship like that,” he tells me. “I have a lot of friends, but I guess they’re more acquaintances. We spend time together. We work on cars and things. But it’s not a whole friendship.” This weekend, Everitt tells me, has taught him that he doesn’t have to hold his tears back, that he can be vulnerable around his buddies, his girlfriend, his son. “I’ll go home and talk to the woman about it, explain what it’s like to see 50,000 men cry.”

IT’S EASY TO FEEL MOVED BY THIS MASS DISPLAY of vulnerability. Even though I’m a nonbeliever, by early afternoon I’m feeling the emotional power of 50,000 men united in prayer and song, and letting the tears fall as we sing “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” But the tears dry quickly when Richard Henton, the senior pastor at Chicago’s Monument of Faith Evangelistic Church, takes the podium.

Henton delivers the lesson in male dominance that I’ve been dreading. “The head of every woman is a man. The head of every man is Christ. And the head of Christ is God,” he declares. Henton talks about a metaphorical parade “down the avenue of time” with God in the lead and women bringing up the rear. “I can hear the drums,” he says. “And man went left, woman went right. Man wanted to be a she. Woman wanted to be a he. God said, ‘I didn’t plan it that way. I intended you to stay in line!'” With the crowd pumped, Henton promises, “God is bringing man back to His lordship.”

I’m not sure what makes me shudder more, Henton’s message of rigid sex roles or the thousands of men cheering in response. But what most strikes me about his sermon is how much it clashes with everything that came before it, in tone if not theology. No one else this weekend has harped on male authority. Instead, speaker after speaker has encouraged the men to support their wives’ personal and professional ambitions; to become better listeners; to keep their tempers in check; to spend more time rearing the children and helping with housework. For all the media’s focus on PK’s sexism, the men I’ve met seem to be losing their machismo by the minute.

Feminists who have attended Promise Keepers rallies have noticed this, too. In July 1996, Mary Stewart Van Leeuwen, a resident scholar at Eastern College’s Center for Christian Women in Leadership, applied for press credentials and attended a PK conference with a woman colleague. (Women aren’t allowed to attend PK rallies, except as volunteers or members of the media.) “Neither of us detected the least tendency to treat women as any kind of a polluting, inferior, or unwelcome presence,” she later reported. “If anything, the men seemed delighted for an opportunity to practice the kind of Christian chivalry toward women being commended to them from the podium…. Of course, chivalrous attitudes [toward] women do not necessarily indicate feminist sensibilities,…[but] underneath the rhetoric of chivalry and noblesse oblige, Promise Keepers provides a supportive yet challenging environment in which—much as in a twelve-step program—men can turn over a new leaf.”

Van Leeuwen believes that PK’s followers are “better men than their theories.” She points out that PK’s own magazine has stated that the strongest marriages are the ones in which each partner “encourages the other’s pursuit of their dreams—whether it’s becoming a doctor or learning to whittle wood.”

IN BETWEEN SATURDAY’S PREACHINGS, I make an unexpected friend. Jim Miller, 33, doesn’t fit my stereotype of an evangelical Christian. The lanky, 6-foot-3-inch administrator at Ford Motor Co. seems like the type of guy you might run into at one of those restaurants with exposed brick and track lighting. But he’s always the first one to throw his hands up during the musical worship or to dance in the aisle or to hug his friends. During lunch, I introduce myself as a reporter, and he treats me like a long-lost brother.

Three times over the next week, I visit Jim and his family in their brick bungalow in Allen Park, Michigan. One night, his 37-year-old wife, Denise, a full-time homemaker with translucent blue eyes, cooks spinach lasagna for us, then gently chides us after dinner as we sit on the living room floor chattering like teenagers. Reserved and strong-willed, Denise was a single mother struggling to make ends meet when the couple first met at a Bible study. Jim was a college student who had never lived outside Allen Park. They dated for two years before Jim sat her down near his piano, sang her a Christian song called “This Is the Day,” and asked her to marry him.

Married life proved harder than Jim expected. “I still wanted that freedom of a single person, and being able to spend time with friends and having those relationships,” he tells me. But now he had a 9-year-old stepdaughter, and within three months of the wedding, Denise became pregnant. “God was calling me to something greater, to take care of my children, to encourage my wife in who she was as a woman of God. And me being a dummy, I didn’t grasp that.” Instead, he fell back on his old childhood lessons of what it meant to be a man. “I wanted things to be in a certain order,” he says, “and if they weren’t, I could lose my temper.” He never physically abused his wife, but “we would get into arguments and I would basically mock her. ‘You think you have it so rough. Little Miss Pity. You’re angry with me because I graduated from college.'” As he tells me this, Jim begins crying. “I’m very ashamed,” he says softly. “I didn’t honor her the way God wanted me to honor her.”

In 1996, four years into their marriage, the couple was still struggling. They argued over whether to remain at their Pentecostal-style church. Their youngest daughter had just been born, and Denise was going through postpartum depression. That spring, encouraged by friends, Jim attended his first Promise Keepers conference. He remembers sitting in the arena thinking, How are my wife and children going to look back at my funeral? Are they going to say, “He was a cruel, hard taskmaster”? Or are they going to say, “He poured everything into our lives”? After the weekend, Jim walked up the back steps of his home, and when Denise opened the door, he burst into tears and asked for forgiveness. “It was like I was a pitcher and I was being emptied out on the floor, and I was ready to be filled up with new wine and oil.”

Denise forgave him, and she says the changes since last year have been dramatic. “I feel like he’s listening now, he’s hearing now like he never did before,” she says. “A lot of things were blocking him as a man, blocking our marriage, blocking everything, and those things have been removed.” Shortly after the conference, the couple found a church they both liked, and one day, she says, Jim came home from his men’s Bible study group elated about his new Christian friends. “It was like the Jim that I knew was back—being excited about our family, about himself, about God,” Denise says. “That was when I finally knew: This is what I’ve been waiting for.”

I leave Allen Park with tremendous affection for Jim and Denise—and ambivalence about the organization that brought us together. I think Van Leeuwen said it best when she called Promise Keepers a Rorschach test for evangelicals. Because PK’s messages are so inconsistent, a man can take home any message he wants. If he believes in equality, he’ll listen hardest to the sermons that encourage respect and return home a gentler husband and father. But if he believes in male dominance, he’ll cheer at the sexist speeches and return just as authoritarian and abusive as when he came. We can only hope the first impulse wins out in the long run, that Promise Keepers will produce more Jim Millers—and fewer Marlboro men.