Traveling solo, a homesick American is befriended by a group of macho local males. Can he be himself and still keep their friendship?

Originally published in Salon.com. Reprinted in Wanderlust, edited by Don George (Villard Books, 2000).

THERE’S NOTHING LIKE THE APPROACH OF CARNAVAL to make a guy feel utterly alone. I was in the 3,000-year-old port city of Cádiz, Spain, walking along a jetty that jutted out from the very corner of Europe. But rather than marveling at the ocean crashing against the stone embankment below me, or at the massive ficus trees in the distance, I was struggling against a funk that had enveloped me as fully as the salt air.

The day before, I had been sitting on an airplane, excited about my trip. I imagined alleyways crammed with ancient, crumbling buildings; labyrinthine neighborhoods scented with olives and oranges; sun so intense it would bronze my skin. I couldn’t wait to throw myself into a beery, music-drenched pre-Lenten celebration that had been compared favorably to Rio’s. And yet, from the moment I arrived in town, I had been confronted by an unexpected disorientation. I couldn’t decipher the Gaditano dialect; couldn’t navigate an old city where half the intersections were unmarked; couldn’t shake off my homesickness. The coming Carnaval, I feared, would only make things worse: I pictured myself, a 37-year-old American with a tenuous grasp of the language, friendless amid the revelry.

I was walking back from the fortress at the end of the pier, seriously considering whether I should catch the next train back to Madrid, when I thought I heard someone call me. I turned around. Sitting on a stone bench, in a limestone alcove that separated the jetty from the gate back into the old city, was a group of 20-year-olds, maybe a dozen of them, mostly male. I immediately felt drawn to them. They looked so approachable, all smiles and sunglasses and baggy sweatshirts and denim jackets. I liked their easy physical intimacy, so common among Spanish men, the casual way hands rested on knees. I wanted to join them. “¿Hablan inglés?” I asked.

Only, those two words took about 10 seconds to force past my lips. My stutter, severe in English, had spiraled out of control in Spanish, so that every word became a battle between brain and breath. I pushed the sounds hard through vocal cords locked in spasm, until finally four discrete syllables tumbled out of my mouth. Ha. Blan. In. Gles.

When I came up for air, they were laughing. Not nervous chuckles but robust, doubled-over guffaws. I had just become the star of their day’s life-comedy. Not in the mood for their mockery, I said, “Adios” and stormed off through the whitewashed gate and back into the old city.

I had gone only a block before I reconsidered. Maybe it was the loneliness I had felt the night before, a terror so visceral that I was on the edge of puking till dawn. Maybe I needed to confront my demons, lest they trail me throughout Carnaval. But something inside me told me to return. So I walked back and looked them straight in the eyes. “I have a problem speaking,” I said. “I’ve had it all my life. I don’t like it.”

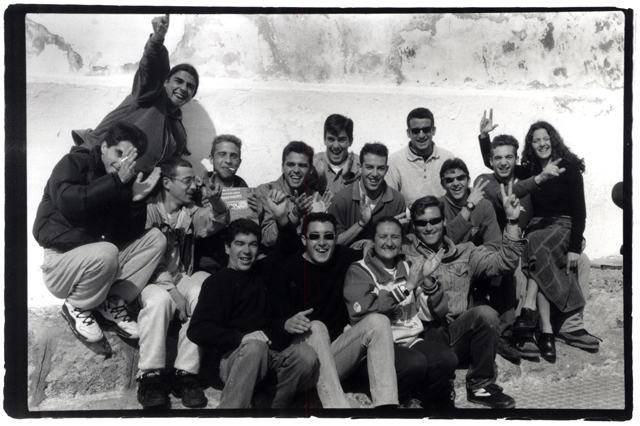

No one laughed. I felt proud of myself. To lighten the mood, I asked if I could photograph them. Suddenly they were beckoning every friend for 50 feet around to join them in the photo, squeezing together tight. They started singing and clapping. I took out my snapshots from home, and everyone crowded around, marveling at my modest white bungalow with its leafy yard. They periodically snickered at the stutter again, but then one would shoot another a look, and the laughter would stop.

That’s how I met The Boys. Throughout that afternoon and evening, these childhood friends—a few of them working blue-collar jobs, but most victim to the city’s 45-percent youth-unemployment rate—initiated me into life on the piers and plazas of the city. They offered me hashish and taught me slang. They proffered a fresh-caught sea urchin, its spiny tennis ball-sized body sliced in half, and instructed me to suck out the fluorescent orange guts. By dinner time, they had decided that no friend of theirs could be without a nickname. So I became El Metralleta, which means “the machine gun.” It was a reference to my stutter, of course, but it was derived from one of the Carnaval groups, a singing gangster family that carried metralletas made of anchovy cans and colored paper.

That night, late, we reconvened outside Falla Theater, a pink Moorish Revival building named after Cádiz’s most famous resident, composer Manuel de Falla. There, a half-dozen groups of teenage balladeers, dressed as sailors and flamenco dancers and disgruntled house painters, stood in the plaza, taking turns serenading the crowd with guitars, drums and joyous vocal harmonies. Between songs, the musicians jumped up and down, shook hands, chanted one another’s names. Then kazoos would sound and another group would start singing. The crowd, pressed in close, cheered and clapped. The Boys were all smiles, soaking in the music and introducing me around. Eight hours into our relationship, I was still a novelty. But my stutter no longer was.

IT BECAME CLEAR THAT IT WAS PHYSICALLY IMPOSSIBLE to go 24 hours without seeing The Boys. Cádiz, squeezed onto a tiny peninsula, was simply too compact. Over the next few days, faces began distinguishing themselves, and names stuck in my head. Late afternoons we would sit on the city beach, chasing the sun along the edge of a stone wall, asking questions about one another’s lives. Do I have a car? A wife? Will I write a book about my travels? If I do, I promised, they would all be in it, and it would be called “El Metralleta en Cádiz.”

Two of them came into greater focus than the others, close buds who went out of their way to make sure I never felt alone. Silva was dark and robust, with thick eyebrows, two hoop earrings and a waist-length ponytail. A camera-ham who managed to squeeze his way into dozens of my photos, he could also get very serious, asking about racism in America and nodding earnestly at my reports. Chano was a former sailor who worked alongside the American troops in Yugoslavia. He had pale blue eyes and curly blond hair and a style that was both gentle and relentlessly observant. He and his girlfriend planned to get married and move to the Canary Islands in the spring, where they would at least have a chance of finding work.

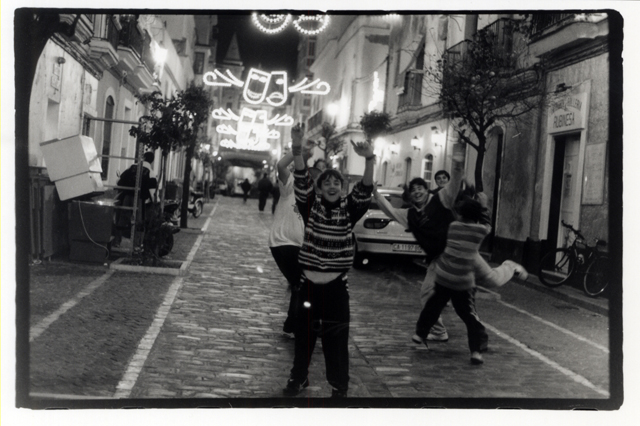

Chano and Silva warned me to save my energy for Saturday night, when all of Cádiz would get dressed up and flood La Viña, the old fishermen’s quarter. So that night, I put on a yellow tasseled face mask and a sailor’s cap and set out. The Boys were right. By 11 p.m., I was caught in a white-water torrent of costumed bodies: nuns and monks, monsters, male brides, cave people. Every cobblestone street was so crowded that I couldn’t see much in front of me. I just let myself be pulled in, enjoying the sensuality of the crowd. Then a street would terminate in a plaza, and a makeshift stage would be set up, where Carnaval bands would be singing satirical songs in complex harmony. Now and then I stopped to listen: to the make-believe Mafia family with their metralletas; a troupe of singing basketball players in polyester sweat suits; a band of white-winged angels with heaven-blue gowns.

It took me until 3:30 a.m. before I caught up with The Boys in Plaza de San Antonio, a grand commons fronted by a luminous, turreted 17th century church. They were with their girlfriends, dark women in flamenco costumes with heavy lipstick and gaudy false lashes. Silva wore an American Indian headdress with feather earrings and a fringed suede jacket. Chano was done up more elaborately as San Pancracio, the saint who’s supposed to bring work to Cádiz. He wore a green satiny robe; a garland of parsley framed his slender face.

My disguise worked. I was able to sneak up on the group without being noticed—and when Silva figured out who I was, I was greeted with cheers and handshakes and the beating of drums. “Metra-lleta!” Bom-bom-bom-bom. “Metra-lleta!” Drinks were placed in my hands—whiskey, beer—and singing erupted, and I was instructed on how to do the flamenco hand-clap to Cádiz’s unofficial chant: Esto es Cai, y aquí hay que mamar. “This is Cádiz, and here you have to suck.”

Chano brought me deeper into the fold with proclamations of lifelong friendship. “You are of Cádiz,” he announced, and gave me a wrap-around hug. Then he took a ceramic shot glass hanging by a string around his neck, wrote Del Chano de Cai—”from Chano of Cádiz”—on it in black marker and placed it around my neck. “For you,” he said. Silva quickly followed by giving me his kazoo, the ubiquitous instrument of Carnaval. And all the while: “Metra-lleta!” Bom-bom-bom-bom. And more alcohol and more hash, and by this point hugs all around.

And constantly there was the introduction of new friends, who would invariably laugh at the stutter before Chano or Silva or someone told them to knock it off. All of the core group went out of their way to be patient, even when I lost patience with myself. They made it clear that they had all the time in the world—relax. They had so many questions about America: How much poverty? Do people own guns? And what about crack? What does it look like? Do people smoke it?

Then, without a discernible signal, we were leaving Plaza de San Antonio, forming a train to stay together, hands on shoulders. We walked deep into La Viña, to Plaza de Cañamaque, a concrete square where a makeshift bar sold San Miguels and men peed uninhibitedly behind the parked cars. Silva and a friend put their arms around each other and serenaded me with a Carnaval song. It was dark, and vaguely menacing, and I felt so enveloped by everyone that the surroundings only made it better. “This is one of the best nights of my life,” I told Chano, and meant it.

I finally left the plaza at 7:30 a.m. Walking back along the coast road, I watched daylight break and the Atlantic turn deep denim blue. I sat on the wall overlooking the ocean while two young recorder players (one with a safety pin through his eyelid and a pierced lip) welcomed the morning with a quiet, tender Greensleeves.

I LEFT CÁDIZ FOR TWO DAYS the next week and traveled north to where everyone sounded like my high-school Spanish teacher. When I returned on Ash Wednesday, Carnaval was still in full swing. I went to La Viña at 10:30 p.m. to listen to some music, but instead I found The Boys. They were passing time in the most garish part of the district, where rows of illuminated hamburger stands cast a fluorescent glow on the otherwise dark and ancient night.

They were in fine spirits, and I was glad to see them. “I was just in Sevilla Province,” I told them, with more than my usual level of clarity, having practiced this little speech, “and I learned something very important. You all don’t speak Spanish! Up there I understood everything. Everything!” My spirited declaration had the intended effect of altering the dynamic—in particular, raising my coolness quotient a bit.

Chano, Silva and a taxi driver friend named Melchor crowded around me. They were loaded with questions. How were the Baroque villages? Did I like them more than Cádiz? The conversation bounced hyperactively from subject to subject. Is there work in America? How much does it pay? Would they hire us? Can we stay with you? What’s the name of your city’s basketball team? The baseball team?

The Durham Bulls, I told them, answering the last question. That piqued their interest. In Gaditano slang, the hand gesture for bull also refers to a cabrón (male goat): a man whose wife cheats on him. Chano tried to explain this concept to me. “If I’m Silva’s wife—which I’m not—and I…”—at this point he dry-humped Melchor—”what does that make Silva?” I ran through my mental dictionary and came up with the English word “cuckold.” They liked this a lot. “Cuckold!” they laughed, pointing at each other. “Cuckold!” they called out to every male friend who passed by. “Cuck-o-o-old!” Chano shouted, his hands a megaphone.

Then Chano asked me the English for another slang word, mariquita. I was stumped. “Maricón,” he said, putting an arm around Chano’s shoulder. “Man and man, instead of man and woman.” A pause. “Which we’re not.”

“Gay,” I said, but I stuttered a lot. Despite Cádiz’s reputation for tolerance of homosexuality, I had decided not to discuss my own orientation with The Boys. They had already come far in accepting my foreignness, my stutter, my age. I didn’t want to pit my personal realities against the church’s teachings and their own collective machismo.

But Chano was stubborn. About a half-hour later, after I had already forgotten the Spanish word, he asked me in front of the others, “Are you mariquita?” When I drew a blank, he pointed rapidly to himself and Silva. “Man and man,” he said. Another pause. “Which we’re not. You’re not, are you?”

Earlier in the evening, I had gone to an Ash Wednesday mass. As we lined up in front of the gilded altar for ashes—”from dust you came and to dust you shall return”—a woman read a litany of supplications. Her words, her voice, resonated with eerie repetition. Father forgive us for violence. Father forgive us for individual and collective sin. Father forgive us for not following Christ’s words in our lives. Father forgive us for lying.

Forgive us for lying. I realized that if I denied Chano’s question, I’d be stepping into a bigger deception than I could live with. “If I said, yes, I’m gay, what would your reaction be?” I asked.

“My reaction?” Chano replied. “Es igual.” It’s equal. Gay, straight. Doesn’t matter.

Not fully believing him, I took a deep breath. “OK,” I said. “I am.”

I knew at that moment I was potentially changing the entire course of the trip, perhaps casting myself back into the stomach-turning loneliness I experienced on my first night. I was unprepared for the simplicity of their reaction. All three of them, simultaneously, without consulting the others, reached out to shake my hand. I would have felt profound relief if I was not so stunned by what I had just done. “In the United States, if you tell the wrong person you’re gay,” I started, and Chano made a motion of slitting his own throat.

“Here,” he said, “it’s no big deal.”

And it truly was no big deal to Silva and Melchor. I didn’t detect a moment’s pause or a smidgen less affection. It was Chano, to my surprise, who had some sorting out to do. He needed to tell me, for the fourth time, that he wasn’t gay. He assured me that he had no problems with having gay friends, as long as they didn’t try to feel him up. And then came the biggie. “Man and woman is better,” he said.

“Why?” I asked, to which he replied, “Because man and man is anti-natural.”

I conjured up every ounce of my 37-year-old authority. “For you, it’s anti-natural,” I said. “For me, it’s natural.”

This seemed to satisfy him. But just to reseal the friendship, I bought the next round of San Miguels.

Nothing more was said. The party resumed. Chano and Silva were delighted with their new word, “cuckold.” After a while, I set out with my original intention of finding music. I would never have thought the week would take this turn, or that I would quench my loneliness with this unpredictable group of men, who were fascinated by my stutter but mostly shrugged at my sexuality.

THROUGHOUT MY STAY IN CÁDIZ, I thought about redemption. The Boys had started out in my mind as my childhood bullies, the ones who devoted their entire elementary school career to taunting me because of my stutter. So much had changed in 10 days. How easy it would have been to let my initial prejudices rob me of what became a treasured relationship. How easy it would have been for The Boys to do the same.

I had romantic plans for the end of my trip, the final blowout weekend of Carnaval. In my fantasy, we’d be together—Silva, Chano and the rest—and I’d make a speech announcing my departure. “I speak English and you speak all Spanish, but friendship speaks all languages,” I’d tell them.

I met up with Chano and two of his friends at 4 o’clock Sunday morning, back in Plaza de San Antonio. All three were talking quickly, and I couldn’t figure out their plans, but they made it clear I’d be part of those plans. The gist was that we were walking to Plaza de Mina, a few blocks away. Chano would try to do some business, and if he succeeded, he would take us all to an expensive dance in a waterfront amphitheater. Silva was already there, dancing his butt off, and so was Chano’s fiancée.

The plaza was a web of revelers—dense knots of people, mostly in costume, connected by well-trafficked pathways lined with lush North African palms. There was drumming, the drinking of manzanilla and laughter everywhere. Chano seemed to know everybody. But he couldn’t make his sale.

It was evident the evening was careening rapidly toward anticlimax. I didn’t want my last memory of Cádiz to be watching The Boys wistfully sitting outside the dance. So I bailed. I gave my little speech to Chano alone, gave him my sailor’s cap and a short sloppy hug, and walked off.

But, as on the day we met, I didn’t feel comfortable with my hasty exit. So I returned, and asked him to tell Silva goodbye for me. “I will tell him he’s a good friend to you,” Chano said. My last words were supposed to be, “Give a hug to Silva for me.” But I only got as far as “Give a hug,” and Chano pulled me into a strong, tender, not-at-all reticent embrace. As I walked away again, I heard a loud whistle. I turned around and saw Chano for the last time, feverishly waving goodbye.