Confronted with desperately ill unborn twins and great risks to her own health, a young woman steps into a political minefield.

By Gina Gonzales as told to Barry Yeoman. Originally published in Glamour.

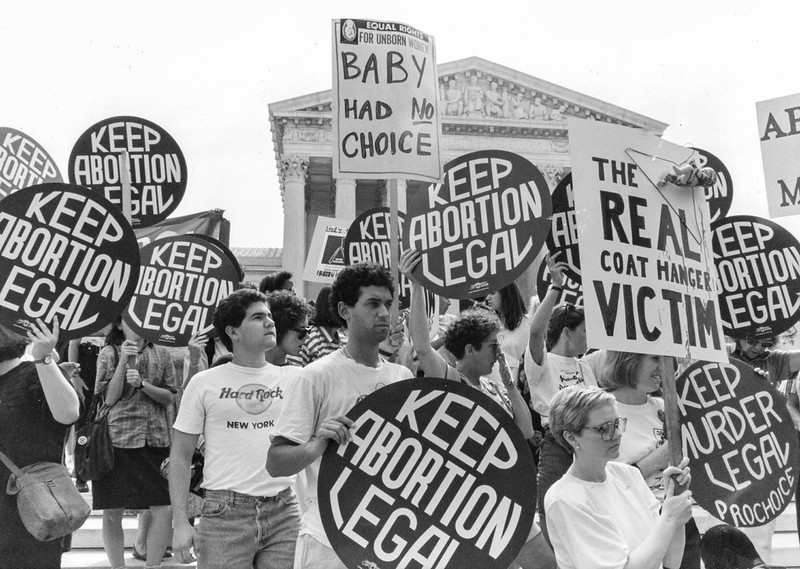

Pro-choice and anti-abortion demonstrators stage concurrent events outside the U.S. Supreme in 1989. Photo by Lorie Shaull ; published under a Creative Commons CC BY 2.0 license.

I NEVER THOUGHT I WOULD CARE PASSIONATELY about the abortion issue or that I would find myself defending one of the most controversial medical procedures a woman can have. But then, during a routine ultrasound in April 2000, my life changed completely.

“It’s a girl,” said the technician, scanning the first of my babies.

I was so filled with joy that tears came to my eyes. For four years, my husband, John, and I had been trying to start a family. I’d had three miscarriages and was starting to believe it was never going to happen. But after treating me for endometriosis and a uterine polyp, doctors told me I would finally be able to carry a pregnancy to term. Six months later, at age 27, I discovered I was pregnant, and soon after I learned that I was carrying twins, which run in my family.

For four months, my husband and I prepared for the arrival of our children. We furnished their bedroom with matching cribs, and my mother started sketching a wall mural of Noah’s Ark because of the animals entering in twos. We registered for gifts. We picked out four names—two for boys and two for girls. And we went through a battery of sonograms, all of which indicated that the babies were healthy. By the time we got to the more detailed 20-week ultrasound, our biggest question was, What sex are they? I wanted daughters—I had visions of Girl Scouts and fishing trips. So when I learned that the first baby was a girl, I was thrilled.

And then the ultrasound technician uttered a single syllable: “Oh.”

I squeezed my husband’s hand. “Is something wrong?” I asked.

“The doctor will talk to you about it,” she responded flatly. She continued with the scan and soon informed us that the second twin was a girl too, but by this point my excitement was overwhelmed by a growing sense of anxiety. What was wrong?

I TRIED TO STAY CALM as we waited for the obstetrician on duty at the hospital to deliver the news. “Well, we see some problems here,” he said. The larger of the girls, whom we later decided to call Savanna, had a pair of conditions called fetal hydrops and pleural effusion, which meant that fluid in her head and chest cavity was putting pressure on her internal organs and keeping them from developing properly. The other twin, Sierra, who came from the same egg, was much smaller and had a malformed umbilical cord and smaller vital organs. “We want to do more tests,” he said, “but it doesn’t look good.”

Driving home, I tried not to cry, but I felt like my world was crumbling. John was trying to be strong, but I could tell he was holding back tears.

We had to wait five more days for an appointment at another medical center, where we could have a more sophisticated sonogram along with an amniocentesis and a fetal echocardiogram. My husband and I are devout Christians, and during that time we prayed and prayed, believing that God was going to heal our girls. Instead, the new prognosis was even grimmer than we had anticipated: The twins’ conditions were actually growing worse. Savanna’s fluid had spread around her abdomen, signaling a condition called ascites, which has a wide range of consequences, including putting additional pressure on the organs, thereby causing respiratory distress and heart failure. Sierra had a leaky heart valve. The doctor also suspected that they were developing Twin to Twin Transfusion Syndrome, which meant that Savanna was taking blood from Sierra through their shared placenta. Sierra’s chance of survival outside the womb hovered at around 5 percent—and she was the healthier of the two girls.

When the doctor who performed this second ultrasound suggested I consider terminating the pregnancy, I grew furious. As a Christian and a married woman who desperately wanted a child, I’d never given much thought to abortion. Like many others, I assumed that only women with unwanted pregnancies had the procedure. I wanted my twins to live. We’re not doing that, I thought. There’s just no way. But as John pointed out, Savanna was going to die, and when she did, she would take her sister with her. My doctor also confirmed that Savanna’s illness could trigger a rare syndrome in me: I was mirroring some of her symptoms and retaining fluids. My body was extremely swollen and I could hardly walk. If I continued the pregnancy, I could put my own health at risk too.

WE CALLED OUR PASTOR, who told us there was no cut-and-dried answer and urged us to make whichever decision would bring our daughters the most life. “Whatever you do,” he said, “we’ll support you.” In fact, everyone—relatives, church members, colleagues—offered us their unconditional support throughout the entire process. “Nobody here has walked in your shoes,” our pastor’s wife told us, “and nobody here can judge you.”

After we learned the results of the sonogram and other tests, my heart was in such a frenzy that I couldn’t sleep. I got out of bed, sat at the top of the stairs and bawled uncontrollably, rocking back and forth. My husband couldn’t sleep either. He tossed and turned in bed all night, thinking, God, what are we going to do?

The following day, we called a surgeon across the country who had been recommended by a local specialist because he had developed an experimental procedure to abort one fetus while keeping the other alive. After listening to the litany of complications our girls had, he was frank with us. “I don’t want to do this,” he said. “It’s not going to give you the outcome you’re hoping for.” Even if one of our daughters beat the 5 percent odds for survival, she could have serious physical and mental problems throughout her life. We hung up the phone and just looked at each other. We knew what we had to do. Letting the girls die on their own didn’t seem like an option, because we believed they were suffering while endangering my own health. And even if Sierra could survive the operation, what kind of life would she have? My parents said they would quit their jobs to help care for her, but it didn’t seem right to bring her into the world with such bleak prospects. I thought about what my pastor had said, and to me, giving her the most life meant releasing her to heaven rather than having her suffer on earth.

Because I was now nearly six months pregnant, the doctor wanted me to go to a facility several hours away that specializes in second-trimester abortions. These procedures are protected under Roe v. Wade if the mother’s health or life is at risk, which mine was. Even as I made the appointment, I was still hoping God could save Savanna and Sierra. But if he couldn’t, I wanted to be able to hold them and say goodbye before I lost them forever. “Can you give me my babies intact?” I asked the nurse, who tried to reassure me. “We think we can do that,” she said. “Sometimes we can’t, but we’ll do our best.”

The week before the abortion, I played the piano as much as I could for the babies, and I talked to them, trying to teach them everything I could. I told them that their father and I loved them and that soon they would be with God in heaven. I even told them about fishing. Then I went in for the procedure. For three days, the medical staff dilated me with the natural substance laminaria to ensure that there would be no injury to my cervix, and I stayed in a hotel at night. When I was ready for the surgery, I was given an anesthesia, and while I slept, the physician terminated the pregnancy and then carefully removed Sierra and Savanna from my body vaginally.

After I awoke, the nurse brought my daughters in so that my husband and I could hold and bond with them. Seeing them, I almost forgot they were dead. They weren’t perfect, but to me they were beautiful. Their fingers were so tiny. I remember touching Savanna’s head, and it jiggled from the fluid. Even as we looked at her, we realized how sick she had been. And her sister, so tiny, had been extremely sick too. We looked at Sierra and instantly knew that the sonogram was right: She wouldn’t have made it either.

I DIDN’T KNOW MUCH ABOUT ABORTION before all of this. I didn’t even realize that most women who have abortions don’t get to hold their babies. But I’d had an intact dilation and evacuation (D&E), in which the fetuses were removed whole. It makes so much sense: If you can give a grieving mother a baby to hold afterward, you give her a more healing way to end a wanted pregnancy.

Last summer, I learned that outlawing intact D&Es is a top priority of anti-choice activists, who in an effort to inflame the issue, call the procedure “partial-birth abortion” because the fetus is removed late in the pregnancy. The most humane and safest option John and I had available to us is being threatened by lawmakers who do not understand our heartache. I used to vote straight-ticket Republican, but I couldn’t bring myself to vote for George W. Bush, who used his acceptance speech at the GOP convention to promise to sign a law against “partial-birth abortion.”

In fact, I will never vote for a candidate who wants to take away the procedure I used to release my fatally ill daughters into the arms of God. I have never before been a political activist. But if I have a chance to change even one person’s heart by telling my story, that’s what I want to do for my girls. I want Savanna’s and Sierra’s lives to have meant something.