Why my stutter makes me a better reporter

Originally published in the Journal of Michigan Fellows.

Note: This column has been revised slightly to reflect the current state of the science and the language. It is also a snapshot in time. For a 2019 update on how I currently viewed stuttering, see my essay Stammer Time from The Baffler.

I DIAL THE NUMBER OF A SUBURBAN MOTHER who has an important story to tell. Her family’s experience, I hope, will become the lead of a magazine article I’m writing. “Hello, is this…?” I start to ask when she answers the phone, but my words disintegrate into a guttural cacophony of noise and silence.

As a reporter with a stutter, I have good days and bad ones, days when the words glide out of my mouth, and others when my vocal cords feel as knotted as pretzels. Today is a bad day. She doesn’t answer my question at first. Instead, she lets out a long chortle. In my mind’s eye, she is throwing her head back in amused delight, thinking some friend or relative is playing a prank on her. I’m used to this. Regularly, I talk to sources—secretaries, bureaucrats, even librarians—who think my stutter is the most entertaining thing they’ve heard all week.

They laugh, like the woman I’m interviewing today, or they mimic my stutter back to me. Sometimes they get scared and hang up. Or they ask me if I’m choking and if they need to call 911. One man thought I was a pervert and responded with a rapid stream of sexual innuendo, asking (among other things) whether I wanted to mate with an iguana.

It would be so much easier to be an accountant, I sometimes think. Lock myself in an office and never talk to anyone. And yet journalism is the only career I’ve ever wanted to pursue. When I was growing up, relatives questioned my wisdom; I doubted my own future enough that I entered college as a research-psychology major. That academic trajectory lasted for all of three days, until I came to my senses and decided to study journalism after all. But even a college professor who gave me an A in her class told me I’d never make it as a reporter unless I overcame the stutter.

In the 19 years since I graduated from New York University, I’ve built a career I feel proud of. After many years writing for alternative weeklies—and winning prizes such as the National Magazine Award for Public Interest and the Batten Medal, which honors a three-year body of work—I recently began to freelance full time. Now I write about political, social, and scientific issues for Mother Jones, Discover, Glamour, and a host of other national magazines. I make decent money and turn away almost as many assignments as I accept. These days, I think my success is not in spite of my stutter, but rather because of it. Still, it’s never easy.

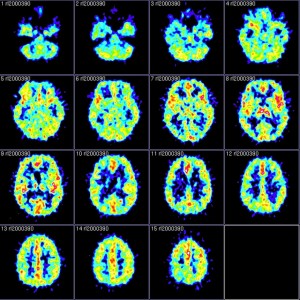

PET scans of the stuttering brain. Photo courtesy of Reigh LeBlanc; reproduced under a Creative Commons license CC BY-NC 2.0.

I DON’T KNOW WHAT CAUSES MY STUTTER, because no one knows. Research has not come up with a single cause of stuttering: Like many conditions, it’s the product of both genetic and neurophysiological factors. Scientists have found structural and functional differences in the brains of people who stutter. Various stresses, including the reactions of impatient listeners, can aggravate the symptoms.

With such a complex syndrome, no one has designed a therapy that eliminates stuttering over the long haul, and the wisest speech-language pathologists have stopped trying to “cure” the problem. Instead, the trend is to help stutterers live with our speech impediments: to make us effective communicators who live with a minimum of shame.

It’s a worthy goal that I embrace intellectually and actually believe on my better days. But stuttering has a way of deflating even the most self-confident speaker. For one, it’s exhausting: I’m convinced that I burn far more calories than the average speaker. Stuttering also involves “secondary symptoms” such as head jerks and facial tics, and I’ve been known to pull muscles just by talking. None of this, though, is as dispiriting as the reactions I get from certain listeners: the recommendations that I talk slower, sing my words, pray for a cure, or think before I speak; the laughter and mockery; the assumption that I must be emotionally or intellectually disabled. Restaurant employees often turn to my dining companions, silently pleading with them to order for me. (“If you’re an acting student, I wish you’d stop,” a server once said to me. “It’s making me nervous.”) An editor told me outright that he wouldn’t hire a stutterer, even though I was the best-qualified candidate.

This ostracism is one of the reasons why I think stuttering makes me a better journalist. As a white male, I otherwise occupy a privileged place in our culture. Aside from the stutter, I haven’t encountered a whole lot of struggle in my life. But my speech impediment has taught me about discrimination, ridicule, and marginalization. It has taught me how easy it is for people to overlook somebody’s brains and talent because of a trait irrelevant to job performance: race, disability, sex, family status, religion, physical appearance. It has helped me empathize with the struggles of African-Americans, single mothers, evangelical Christians, immigrants, teenagers, people in wheelchairs, transgender folks, public-assistance recipients, and those who have chosen (or have been forced into) unconventional lifestyles. I find myself seeking common ground with—or at least seeking to understand—people whose political views are out of the mainstream, even if I strongly disagree with them. I’ve learned to make the extra effort to understand individuals whose lives are unlike mine, because I know how blithely my colleagues might unwittingly dismiss them, or at least lump them into categories (e. g., “the poor”). I know it because of how many people have unwittingly dismissed me.

It’s so easy to talk with people who are able-bodied, affluent, and college-educated. (Politicians and business leaders tend to fall into this category.) They speak in quotable, syntactically correct sentences, with speech that’s easy to understand. They make our jobs easier by providing coherent analyses. Indeed, our research must include interviews with these folks. But when we limit ourselves to them, we strip our journalism of its texture. My stutter is a daily reminder—an alarm that goes off every time I speak—to interview people who might be harder to talk with. That’s why, in fact, I chose to study the lives of marginalized Americans during my year as a Michigan Journalism Fellow.

The other lesson my stutter has offered me is a simple one: Shut up and listen. When I covered the North Carolina state legislature, I was always amused by how much my press-room colleagues savored the sounds of their own voices. I’ve eavesdropped on many an interview where the reporter seemed to be doing more than 50 percent of the talking. I don’t like the sound of my own voice; in fact, I dislike it more than most people do. (When friends tell me they don’t even hear my stutter any more, I look at them incredulously.) Nor do I enjoy the physical effort of speaking. So I’m content to listen to others: to ask them to tell their stories, then sit back for the next two hours, only interrupting them to steer them back on course when they veer away. I don’t even feel compelled to fill the silences; I know someone will fill them, and I prefer that person be the interviewee.

By listening as intently as I do, then following up with gentle fill-in-the-detail questions, I often wind up with rich, nuanced stories—more than I’d get with a more aggressive Q&A style. I think that as a result, my articles have a stronger narrative drive than they might otherwise.

Finally, watching how someone reacts to my stutter often gives me a window into that person’s character. It helps me learn how much patience, empathy, and tolerance for diversity a person has. It also offers my interviewees the opportunity for redemption. After my telephone interview with the suburban mother, she asked if she could tell me something personal. “I hope this isn’t out of line,” she said. “At first, I was nervous hearing your stuttering. That’s why I laughed. But after talking with you, I realize you have guts. I admire you.”