When her fight against cancer became unbearable, Colleen Rice chose death as her only option. Now the U.S. government is challenging the Oregon law that helped her end the agony.

Originally published in AARP The Magazine.

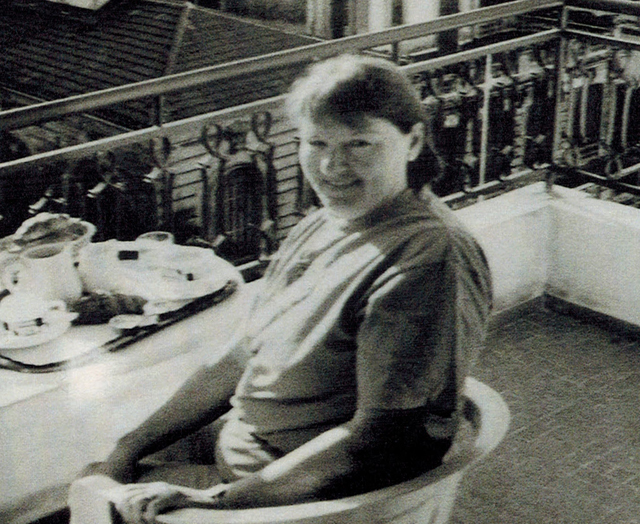

Colleen Rice supported assisted suicide even before she became terminally ill. “People treat their dogs better,” she used to say of the American health-care system.

THE NIGHT BEFORE COLLEEN RICE SWALLOWED THE MEDICATION that ended her life, she wanted to give her grandchildren one final, uncomplicated memory of their family matriarch. So with the kids out of sight, she hobbled upstairs to the bathroom, her daughter holding her steady and carrying the oxygen tank that helped her breathe through cancer-riddled lungs. She showered, put on her white housecoat, and returned to the family room of her daughter’s home in Tigard, Oregon. Wanting quiet for her last night with her loved ones, Colleen removed her breathing apparatus—which she could live without for short periods of time—and with the turn of a switch, the room, usually filled with the whirring of the generator that supplied her oxygen, grew suddenly still. “I’m ready,” she said.

The grandchildren were called in: 20-year-old Joshua, home from the Navy for Christmas; his 16-year-old sister, Ashley; and their 12-year-old cousin, Brendan, visiting with his father from Canada. They crowded around a small circular table—Colleen wanted them as close as possible—and brought out Tock, a French-Canadian game played with marbles, a deck of cards, and a red, white, and black wooden board with a circular center known as Heaven.

Everyone was in high spirits. As the marbles migrated around the Tock board, Joshua entertained the family with his Jim Carrey impersonations and showered his grandmother with kisses and tickles. Colleen laughed hard, even though the laughter attacked her chest with a stabbing pain. “Stop! Stop!” she protested, hating to stifle the merriment on which she thrived. Her daughter, Cathy Paul, knew what most of the kids did not: Their grandmother, whose debilitation and feeling of helplessness were worsening daily, would end her life in less than 12 hours. Cathy struggled to keep smiling as her relatives moved their marbles in and out of Heaven. At one point, Colleen pulled her daughter aside and whispered, “I’m coughing up blood.”

By 11 p.m., Colleen was worn out from the lack of oxygen. “Night, Grandma,” the kids said casually, but Cathy stopped them before they wandered off. “No,” she said. “Give Grandma a hug and a kiss good night.” Inside, she wanted to scream, “Tell her how you feel! This is the last time you’ll see your grandmother’s smile.”

The house quiet, Cathy turned to her mother. “You don’t have to do this,” she said.

“Yes, I do,” the older woman answered. She offered no explanation, but Cathy understood why her mother planned to take a lethal prescription of barbiturates the next morning. The product of a strong Catholic family, Colleen had escaped a deadening first marriage and spent almost four decades on a spiritual and creative quest. The journey carried her to a metaphysics institute, where she studied spiritual issues; to the ends of the U.S. in a motor home, selling her waxwork paintings with her husband, Scott; and to the Atlantic coast of Ireland, where she researched a historical novel. Her work mostly complete at 67, she was now largely confined to the sofa and bed, her senses dulled by morphine, the space between her lungs and chest cavity filling with fluid from her tumor. Left to its own devices, her body would have quit within a couple of months, maybe less, but Colleen didn’t want to experience the misery of suffocating as her lungs became unable to deliver oxygen to her body. Instead, she wanted a quiet, prayerful death, surrounded by her family.

“I’m going to bed now,” she announced. Scott had retired earlier in the evening to be alert when Colleen needed his support in the morning.

“Why don’t we just stay up a bit?” Cathy asked.

“I really need the sleep,” Colleen said, heading toward her room. Tomorrow would be one of the most important days of her life. She needed to be ready.

THE LAW THAT WOULD ALLOW COLLEEN RICE to hasten her death will face a serious challenge this year in a federal appeals court. The Oregon Death With Dignity Act, which allows physicians to write lethal prescriptions for certain terminally ill patients, was used by only 91 Oregonians in its first four years on the books. Yet it has prompted a crusade by U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft, who in November 2001 directed the Drug Enforcement Administration to prohibit doctors who prescribe fatal doses of medicine from writing prescriptions under the Controlled Substances Act. Ashcroft, a longtime opponent of physician-assisted suicide, claims the law violates the Act, which bars doctors from prescribing drugs for anything other than legitimate medical purposes. Though a federal judge blocked Ashcroft from enforcing his order, the issue will not be settled until all courts have weighed in. It seems inevitable that the case will go to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Oregon measure, unique in the nation, was approved twice by voters, despite heavy opposition from the Catholic Church. During those campaigns, critics charged that the law would trigger a “slippery slope”—from voluntary suicide to the Nazi-like extermination of undesirables.

In reality, the Death With Dignity Act is quite specific: It allows state residents with less than six months to live to request medication to end their lives “in a humane and dignified manner.” The patient must ask three times over a period of 15 days or more, twice orally and once in writing. Two physicians must approve the petition, and they must refer the patient to counseling if there are signs of depression or other mental disorders. Finally, the patient has to be able to swallow the drugs without assistance. The physician is not allowed to intervene at the bedside.

In the five years since the law took effect, state officials say it has proceeded without medical complications. Those who have committed assisted suicide typically have been well-educated men and women with both health insurance and access to hospice care. “The critics have been terribly disappointed that the warnings they gave—that this would lead to euthanasia and selective killing of the elderly—have not come true,” says Alan Bates, a physician and state legislator from Ashland. Instead, he says, the law has restored a sense of control to dying Oregonians, even those who don’t end up taking the drugs. “The choice gives them a sense of peace,” he says. “They know that at the end they won’t be in terrible pain.”

Even when they don’t choose assisted suicide, Oregon patients feel more empowered to orchestrate the final months of their lives than patients anywhere else in the nation. The Beaver State leads the U.S. in many of the indicators for top-quality end-of-life care. Oregon consistently shows the lowest rates of in-hospital deaths, and the state ranks first in the use of medical morphine, a key indicator of whether terminally ill patients are receiving adequate pain control. Oregon is also among the top states when it comes to the availability of hospice services.

Yet physician-assisted suicide remains the most controversial aspect of end-of-life care, both in the state and the country—similar measures have failed by close margins in Maine and Hawaii—and some Oregonians are publicly rooting for Ashcroft to prevail. Critics point to data showing that loss of independence, rather than physical pain, is why 94 percent of patients opt for suicide.

“Dying makes us dependent on people, and we don’t like that. We have to learn that it’s okay to be cared for,” says Father John Tuohey, an ethicist in Portland’s Providence Health System who opposes the law. “Is this a good public policy to send out to people: When you become too burdensome, feel free to check out?”

Few people actually choose assisted suicide. In Oregon, 1 percent ask their doctors for prescriptions, and only 0.1 percent receive approval or follow through, says Susan Tolle, director of the Center for Ethics in Health Care at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU). The ones who do hasten their deaths follow a pattern: They are generally self-reliant, accomplished individuals who personify Oregon’s pioneer spirit. “This is a group of people whose life experiences make them value control,” says Linda Ganzini, an OHSU psychiatry professor who has studied the issue. “They often associate being cared for by somebody as humiliating. They develop this fierce individualism. In Oregon, they’re admired for those characteristics.” For people like this, the prospect of spending their last days in a morphine haze, soiling their bed sheets and being turned over by nurses, is worse than death itself. “It’s not that their pain can’t be controlled,” says Katrina Hedberg, a medical epidemiologist for the Oregon Department of Human Services. “It’s that to control it they give up what makes their life meaningful.”

COLLEEN RICE NEVER IMAGINED SHE’D BE CHOOSING between a pain-ridden life and a dignified death when she visited her doctor in September 2000. She was suffering from breathing trouble that had left her fatigued, and doctors suspected asthma. Then a CT scan showed a tumor on one lung. Follow-up tests confirmed the severity of her illness.

Scott, her husband, had accompanied Colleen on all her doctor visits, so he was prepared for the worst, doing most of his grieving in long phone calls to Colleen’s sisters. But when Colleen calmly told her daughter the news—that she only had six months to live—Cathy collapsed. “My life got sucked out of me,” remembers Cathy.

Colleen remained strong—a strength that had only grown throughout her life. One of six kids in an Irish Catholic family in Ottawa, she married a neighborhood boy at 20 and moved to a military base in a remote subarctic town in Manitoba, where she scrubbed the tile floors daily and kept the radio tuned to reports of polar-bear sightings. It was only after her divorce 10 years later, and her move back to Ottawa, that she began the inner journey she had long delayed, taking classes in religion, dreams, and meditation, and meeting her future husband, Scott. She was 39. He was 22. “She was young for her age, and I was old for mine,” he recalls three decades later. “She was loosening up and learning to play.” They married in 1976 and eventually moved to Oregon, where they took an interest in an art form called CireCraft, which uses crayon wax, a travel iron, and a hot plate to create intricate landscapes. Before long they bought an orange and black Cabana motor home, christened it Pumpkin, and began a three-year road trip to show and sell their art. In 1985, Colleen began her last great adventure. She signed up for a Writer’s Digest correspondence course and started a historical novel, which would occupy the rest of her life and involve three research trips to Ireland’s rugged Atlantic coast.

Now, with her book unpublished and her health going downhill, Colleen kept a calm exterior. There were decisions to make. The doctors told her that chemotherapy might extend her life by months but would not cure the cancer. Colleen decided she had too much unfinished business to be crippled by chemo’s side effects. Instead, she opted for palliative, or comfort, care. Hospice workers provided oxygen to help her breathe, along with morphine to ease the pain and relieve her sense of breathlessness. They treated the side effects of her medication and made available a 24-hour nurse who could be telephoned in emergencies. With her basic comfort provided for, Colleen used her final months—there were only three, it turned out—to complete the most important tasks of her life: healing some long-standing conflicts with Cathy and enlisting the family to help edit her novel.

She also began the process of requesting a lethal prescription. Colleen had been aware of the physician-assisted suicide issue for almost a decade and had supported it during the 1994 and 1997 referenda. “People treat their dogs better,” she had said of the American medical system, which generally requires that doctors keep patients alive no matter what. She surely knew the profound, almost ironic effect the law has had on end-of-life care in Oregon. The more patients inquire about hastening their deaths, the more doctors search for alternatives to alleviate their suffering. Since the state’s first death-with-dignity vote eight years ago, health care institutions have been scrambling to stay on the cutting edge of quality-of-life care for the terminally ill. In 1995, OHSU started building its own comfort-care team for dying patients in hospitals—a radical innovation in a profession that aims to cure rather than soothe the sick. Professional organizations are presenting more end-of-life-care workshops. “People wouldn’t go to those before the law,” says Barbara Coombs Lee, president of the Compassion in Dying Federation. “Now it’s standing room only.”

The law has also pushed the state’s news media to examine end-of-life issues, including pain management and hospice availability. In turn, Oregonians are increasingly insisting on top-notch care for terminal patients. “When I was in medical school, you’d never see a family walk up to a doctor and say, ‘This is not what our mother would have wanted,'” says OHSU’s Susan Tolle. “The Oregon vote was a wake-up call for medicine.”

But critics such as Joanne Lynn, director of the Washington Home Center for Palliative Care Studies in Washington, D.C., warn against applying the lessons of one state to the rest of the country. Oregon has been successful, she says, because it’s a forward-thinking, fairly affluent place that guarantees health care to its citizens. It had a strong infrastructure to care for the terminally ill. By contrast, Maine (where voters defeated a proposed death-with-dignity law in 2000) has one of the lowest uses of the Medicare hospice benefit of any state. It would need to guarantee universal hospice and palliative care if such a law were passed, says Ganzini, the OHSU psychiatrist. Allowing assisted suicide in Maine, she says, “seems like a pretty bad idea.”

FOR THE LAST MONTHS OF HER LIFE, Colleen Rice lived at her daughter’s house in a makeshift bedroom adorned with a miniature statue of an angel, a Lakota Indian prayer, and a rosary an ancestor had brought over during the Irish potato famine. At night Scott lay awake, listening to his wife’s breathing in the hospital bed a foot away, and hearing Jasmine, their German shorthaired pointer, snoring on his other side. He synchronized his breathing with Colleen’s. Sometimes, when her respiration slowed, he’d take two breaths for every one of hers. Other times Colleen would wake up, angry at still being alive, worried that if she waited too long she would no longer be able to swallow the medication by herself. If that happened, anyone who assisted her would be breaking the law.

On the final morning, at 5 a.m., there was a knock at the door. Standing outside was George Eighmey, executive director of Compassion in Dying of Oregon. Since the passage of the law, Eighmey and his volunteers have visited families, located sympathetic doctors and pharmacists, and stood at bedsides at the end when asked.

“Here’s Mr. Death,” Colleen said, deadpan, as he walked through the door, then broke into laughter.

Colleen had put on her makeup that morning. She wanted to look good on her final day. She took an anti-nausea medication to ensure that she wouldn’t vomit the bitter-tasting barbiturates later in the morning. Eighmey explained the procedure to the family, then helped them crush the 90 barbiturates and mix their contents with orange juice to make swallowing easier.

Finally, after the anti-nausea drug had taken effect, the family gathered around. Outside, it was still black. “I remember walking into the bedroom,” says Eighmey. “It might sound strange, but there was a softness in the air, a feeling of warmth. Colleen was such a warm, reassuring woman, she gave others permission to feel sad and to participate.”

When the time came, Eighmey asked Colleen her wishes one last time. “Are you absolutely sure you want to do this?”

“Yep, let’s do it,” Colleen replied matter-of-factly.

“Colleen, it’s not too late to back out,” Eighmey said. “If you have any hesitation, we can dump this down the toilet.”

“Nope,” she responded. “I’m ready.”

After a quick toast, she lifted the glass and drank. Almost immediately she began to doze. Cathy started reciting the Lakota prayer that would fill the room for the next two hours:

O Great Spirit,

whose voice I hear in the winds,

and whose breath gives

life to all the world, hear me!

I am small and weak.

I need your strength and wisdom.

Between each verse, her relatives chanted. “We let you go,” they said. “Go to the light. We love you. Find the light.” Then, one by one, her family recited the next verses, broken up by more chanting, until finally.

Make me always ready

to come to you with clean hands

and straight eyes, so when life fades,

as the fading sunset, my spirit

will come to you without shame.

Within minutes Colleen had slipped into a coma. The dawn broke bright and warm, a startling contrast to the usual rain of December mornings. The family kept up their prayer, punctuated by exhortations: “We release you. Find the light.”

Two hours after she took the medicine, Colleen Rice was gone. Everyone left the room except Cathy, who sat with her mother for a few minutes before waking her children. Eighmey dialed the hospice to report an “expected death.” The death certificate cited the cause as lung cancer.

Two years later, Cathy still breaks down when she recalls her mother’s illness and hastened death. Sometimes she imagines what her mother would be doing if the cancer had gone away. Then she remembers the Ashcroft directive, and knows exactly what Colleen would be up to. “If she had been cured,” Cathy says, “she would be standing on some steps in Washington, D.C., shouting, ‘How dare you take away our right to die in dignity? You don’t have that right.'”

SIDEBAR: Switching Sides

Why one of the biggest supporters of doctor-assisted suicide has changed her mind

In 1992, Diane Meier, M.D., co-authored some of the first guidelines for doctor-assisted suicide. “My sense was that patients were the only ones who knew what was best for them,” says Meier, director of the palliative care program at New York’s Mount Sinai School of Medicine. “The medical profession’s opposition to physician-assisted suicide seemed breathtakingly arrogant.”

In the decade since, Meier has become one of the premier opponents of death-with-dignity laws. She now believes that existential despair, not physical pain, is what motivates many patients to end their lives—and that most doctors are ill-equipped to deal with the psychological components of serious illness.

Meier’s about-face was spurred by a patient, an 87-year-old immigrant who lived alone and battled a series of chronic health problems: diabetes, high blood pressure, arthritis, loss of hearing and sight. The patient could barely walk. She was constantly irritable. Unable to live as she was accustomed, “her life frame was shrinking,” Meier says. “Several times she said she just wanted me to give her a pill.”

Since assisted suicide is not legal in New York—nor is it legal anywhere in the U.S. for patients without terminal illnesses—Meier resorted to a treatment that her colleagues frequently overlook. She listened to the woman’s litany of problems: her guilt at having been a bad parent to her now-adult children, her anger at their rejection. With the patient’s permission, Meier called the woman’s adult children and encouraged them to set aside their old resentments. They heeded the doctor’s words, taking turns visiting their mother. “By the end of her life, her relationships with her kids were healed,” Meier says. “It wasn’t until that happened that she allowed herself to die.” One day she told Meier, “I’m going to die in five days and see my husband on the other side.” And she did.

When a patient asks to die, “nine times out of ten it’s an expression of despair and a communication to the physician to hear the despair,” says Meier. Unfortunately, most doctors are either ill-equipped or too busy to explore these feelings. Allowing doctors with limited repertoires to prescribe lethal medicines, she believes, is dangerous public policy.