Years of struggle taught Charlotte, North Carolina, and other American cities that diversity is a growth industry.

Originally published in AARP The Magazine.

Charlotte TV station WBTV looks back at the student sit-ins in Charlotte.

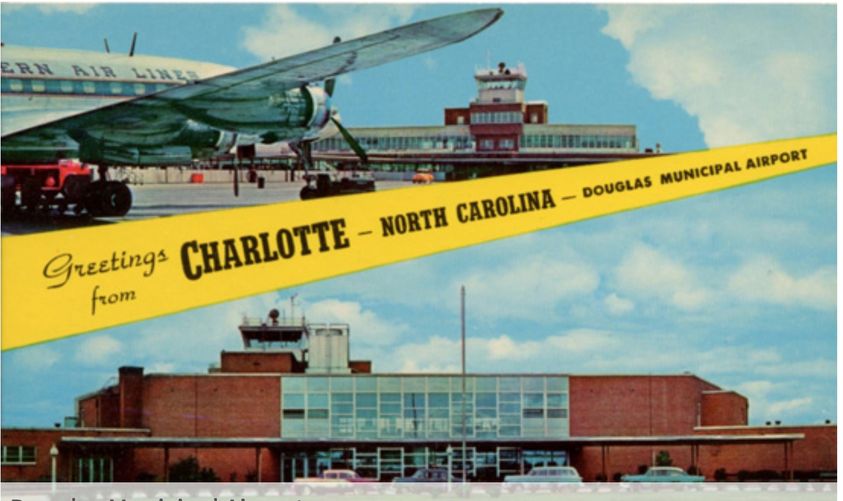

REGINALD HAWKINS COULD FEEL HIS HEART RACING as he and three friends made their way through Douglas Municipal Airport in Charlotte, North Carolina. Dressed in his best Sunday suit, the 30-year-old dentist and Presbyterian minister sought to accomplish a simple task: to sit at the Airport “77” Restaurant, with its big picture windows overlooking the two asphalt runways, and eat his lunch unmolested.

Hawkins was small and bespectacled, but he carried himself with an unmistakable fierceness. As he saw it, the federally funded airport’s facilities were required to serve African Americans like himself. But Hawkins also understood the social order in Charlotte in 1954. Like most Southern cities, it insisted on total racial separation. When he and his friends had approached the restaurant a few days earlier, the hostess had said, “We don’t serve blacks here.” Armed with this rejection, the four had appeared before the Charlotte City Council, threatening to sue the city if the discrimination persisted.

It was a bold gambit for its time. Just weeks had passed since the Supreme Court had issued its Brown v. Board of Education decision, the first major step toward dismantling Jim Crow segregation. Lynchings still made the news, and even the mildest protests met with harsh white resistance. In Macon, Georgia, two men—one white, one black—had just been jailed for the crime of socializing together.

But Hawkins pressed on. As he and the others entered the restaurant, the hostess again tried to stop them. This time, the four brushed past her, spotted an empty table, and took their seats. The ensuing commotion caught the ear of Frank Littlejohn, Charlotte’s chief of police, who was at lunch with several city bigwigs. The chief knew Hawkins from previous protests. He walked over to the dentist’s table. “Doctor, won’t you all leave?” he said. “You’re embarrassing us.”

“I’m sorry,” Hawkins replied. “But we’ve been embarrassed all our lives.”

And here’s where our story departs from similar events happening at that time in the South. Littlejohn went to talk to the restaurant manager. When he returned, his demeanor was different. Perhaps the chief really believed the law was on the protesters’ side. More likely, he wanted to spare Charlotte the notoriety of jailing four well-dressed professionals for such a benign act. Littlejohn told the men they could stay.

It would take two more years of agitating before blacks would be guaranteed seats at the Airport “77” Restaurant. Still, that small victory 50 years ago is symbolic of a remarkable civil rights battle that history has largely forgotten: the story of how Charlotte and a few other forward-thinking Southern cities painstakingly dismantled Jim Crow laws without bursting violently apart in the process.

To be sure, the decade after the Brown ruling produced stories that seared the conscience of the world. In Montgomery, Alabama, police arrested Rosa Parks for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus. In Little Rock, Arkansas, Governor Orval Faubus called out the National Guard to block African American children from entering Central High School. In Birmingham, Alabama, public safety commissioner Bull Connor turned fire hoses and police dogs on civil rights demonstrators.

But in Charlotte, civic leaders worked to avoid confrontation, believing that the city’s growth and prosperity depended on its ability to embrace the new era. Today, many of them see a direct line between a Southern city’s present quality of life and how it approached the Civil Rights Movement decades ago. And they may be right. Cities like Charlotte, which managed to abolish Jim Crow without bloodshed if not without tears, are the jewels in the crown of the New South. Once, Southerners headed north in great numbers—many fleeing poverty and discrimination. But today, the reverse is true. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of people who move from the Northeast to the South each year is more than double the migration in the opposite direction. And it’s the places that practiced racial moderation—Charlotte, Jacksonville, Nashville, Atlanta, Dallas—that have prospered from this explosive growth over the past half century.

Back in 1950, according to the last census before the Brown decision, Charlotte was the nation’s 70th-largest city. Its population of 134,000 was less than half that of Birmingham. Since then, Charlotte has shot up to 21st place, with 581,000 residents, while Birmingham’s population has actually fallen by more than a quarter. Charlotteans believe it’s no coincidence that the city that used diplomacy blossomed while the city that used attack dogs did not.

“What made Charlotte a modern city, a city that didn’t bleed, is that you had a strong business community that tried to stay in front of anything that would give a negative impression,” says former Charlotte mayor Harvey Gantt, who in 1983 became the first African American to head a large, predominantly white Southern city. “The leadership wanted to project an image to the nation that we could deal with the racial issue without becoming another Birmingham.”

That image didn’t come easily. At times, Charlotte came perilously close to being blown apart—by angry white mobs, by defiant politicians, by bomb scares, and eventually even by bombs. But in each case, civic leaders managed to preserve the city’s reputation—and its peace.

ONE FEBRUARY NIGHT IN 1960, 22-YEAR-OLD CHARLES JONES was driving his Buick to Charlotte, where he was a student leader at Johnson C. Smith University, a historically black Presbyterian campus. Sometime around 4 a.m., the radio broadcast an astounding report: 90 miles from home, in Greensboro, North Carolina, African American students had sat down at a Woolworth’s lunch counter and refused to get up, even as Klansmen taunted them. “Yes!” Jones said aloud. “This is the handle for our generation.” He knew about Hawkins’s success six years earlier at the airport—it was still the only place in Charlotte where blacks and whites could dine together—and he considered it the “first small step of hope.” But he also knew the city’s elite would not make more concessions without more pressure. Hearing about Greensboro, Jones felt the time had come for aggressive action in Charlotte.

The next day, Jones showed up at a student council meeting and threw down the gauntlet. He planned to go down to the Charlotte Woolworth’s, he said, even if he had to go alone: “I’m gonna sit, and I ain’t gonna get up until they open up.” When Jones arrived the following day, 200 students were waiting for him—one fourth of the student body. Risking mob violence, police brutality, and the stain of a criminal record, the students shut down Charlotte’s whites-only lunch counters one by one. Woolworth’s. Kress. McLellan’s. As Jones gave interviews to the local press that first day, his classmates ran to him with breathless progress reports: “Charles, we just closed down Grant’s. We’re going to Belk’s.”

Unlike their counterparts farther south, though, Charlotte’s leaders didn’t respond with fire hoses or mass arrests. Instead, Mayor James Smith and Chamber of Commerce president Stanford Brookshire announced a new biracial committee on race relations. Their motivation was less ethical than financial: the two men worried that noisy protests would disrupt business. “It seems odd now,” Brookshire would later say, “that Mayor Smith and I… were overlooking both the legal and moral aspects of the problem.” The committee spent the next five months trying to negotiate a peaceful desegregation. Finally, to avoid a threatened boycott by the black community of the whole downtown, the lunch counters relented. Charlotte had dodged the headlines once again.

The next years were some of the most violent throughout the South: firebombs, mass arrests, fatal riots. Charlotte’s leaders desperately wanted to avoid confrontations such as these. It began promoting itself as the “Spearhead of the South,” leading the region to a friendly, progressive future. Meanwhile, activists like Hawkins pressed to desegregate all public accommodations. Hawkins held demonstrations; he announced boycotts; he threatened to embarrass image-conscious Charlotte. “We will not be pacified with gradualism,” he declared.

In 1961, Brookshire became mayor. He knew that racial animosity was plunging the Deep South into recession. Birmingham’s hostility to the Freedom Riders who tried to desegregate interstate buses had cost more than $40 million in investment from a single Ohio firm. Little Rock had not seen a major industrial expansion in four years. Brookshire had a hunch about how to spare Charlotte from noisy protests by militants like Hawkins: by cooperating with diplomatic black leaders like NAACP state president Kelly Alexander Sr. Alexander’s son, Kelly Jr., calls the interplay between his father and Hawkins a form of “good cop, bad cop” that kept up the pressure for change: “If you don’t have a bad cop—if they can’t look out the window and see old so-and-so marching back and forth and raising hell—there’s no impetus around the table to get anything accomplished with any speed,” he recalls.

The first test came in 1963, when Brookshire brokered the desegregation of Charlotte’s white-tablecloth restaurants. He quietly arranged for white professionals to invite black professionals to lunch—something they were willing to do in order to avoid more protests—and convinced the media not to report the details until after the fact, also for the good of the city. When the news finally was reported, the public response was a collective yawn.

What Brookshire couldn’t know was that Charlotte’s biggest and most dangerous struggle was still two years in the future. Jim Crow’s violent death throes would ultimately drag Charlotte into the conflict that was roiling the region. And the city’s attempt to use diplomacy to avoid bloodshed—and bad publicity—would face its harshest test.

CHARLOTTE HAD REACTED TO BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION with only token desegregation. Back in 1957, it had allowed four black children to attend all-white schools. At Harding High, whites spat on tall, graceful Dorothy Counts and pelted her with ice as she tried to attend class. “Someone hit me in the back of my head with a sharp object,” she recalls. “That was the first time I felt violated.” Finally, she transferred to a private school up north.

By 1964, ten years after Brown, only 800 of Charlotte’s more than 20,000 African American public school students attended school with whites. But Darius and Vera Swann, black Presbyterian missionaries recently returned home from India, challenged the status quo. In 1965, after their son was barred from attending an integrated school, the Swanns filed suit—and released a torrent of racism. The prospect of fully integrated schools repulsed some white Charlotteans and moved at least one to horrifying violence.

On November 22, 1965, Reginald Hawkins woke to a blast that shattered not only the windows in his children’s playroom but also Charlotte’s illusions of invulnerability to the violent clashes of the Deep South. Early that drizzly morning, four bombs went off almost simultaneously in the homes of Hawkins, Swann attorney Julius Chambers, Kelly Alexander Sr., and his brother, Fred. No one was hurt, and the bombers were never caught, but all four homes were extensively damaged and the flying glass came perilously close to slashing two of the Alexander children. For Hawkins, it was a reminder that the crusade for equality could, at any time, turn lethal. “I knew that day they were out to kill me,” he says. “I had already talked to Jesus about the role that I had to undergo. Any man that was afraid for his life didn’t have a life.”

Instead of inflaming racial tensions, though, the bombings seemed to quell them. Local leaders worried about the city’s reputation. “The good name of North Carolina is at stake,” editorialized The Charlotte Observer. Mayor Brookshire organized a relief fund and raised more money than was actually needed to repair the houses. The mayor also urged Charlotteans to attend a racial-harmony rally the following week—and thousands showed up. “It was the kind of response you get when a community rallies around flood or hurricane victims,” says Kelly Alexander Jr.

The unity lasted until 1969, when federal judge James McMillan issued his ruling in the Swann case. A white jurist not known for radical thinking, McMillan nonetheless wrote that the school board must act immediately to desegregate, even if it meant busing children away from their own neighborhoods. Charlotte became the nation’s test case for school busing.

Reaction was harsh. Furious white parents flooded board of education meetings. Board members angered McMillan by submitting plans that left some schools segregated. Bomb scares proliferated. But as McMillan rejected one temporary plan after another, forcing children to shift from one school to the next, Charlotteans grew weary of the instability. Ministers, neighborhood leaders, and politicians began to step forward, announcing that it was time to cooperate with the courts.

In 1973, a group of 25 citizens—black and white, pro- and antibusing—began hammering out a plan. “We had a great camaraderie between moderate whites and blacks that was rather amazing when you look back at it,” says Maggie Ray, the homemaker who led the group. “We were shoulder to shoulder—it was exhilarating.” Busing opponents developed respect and affection for their one-time adversaries, and vice versa. Author Frye Gaillard recalls how, when the debates grew heated, one opponent would lean back in his chair, breaking the tension with the good-humored declaration, “Picky, picky, picky!”

From those meetings, Charlotte developed a fully and peacefully-integrated school system by the mid-1970s. White flight to private schools and outlying counties was minimal compared with other Southern cities. Test scores rose systemwide. While racism hardly disappeared, many African American and white students came to shrug off their differences. “I’ve been going to school with blacks all my life,” West Charlotte High School senior Casey Smith told an Atlanta Journal reporter in 1987. “They’re not another race. They’re just my friends.”

A HALF-CENTURY AFTER HE FORCED THE AIRPORT “77” RESTAURANT to serve African Americans, Reginald Hawkins is no longer agitating. With arthritis slowing him down, he spends his days “listening to the Lord” at his lakeside retirement home near Charlotte. Still, at 80, Hawkins maintains the look of a fighter, bejeweled in turquoise and gold, his hair slicked back Al Sharpton-style. Playing his usual bad-cop role, he says Charlotte still has a long way to go to become a race-blind city. “It claimed that it did these things voluntarily,” he says, his voice gravelly and emphatic. “But Charlotte is more interested in the banking interests, economic interests, than it is with justice.”

Others reflect in more measured tones. “Some people still harbor hatred,” says Julius Chambers, who, after the Swann decision, went on to head the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and now practices law in Charlotte again. “But all in all, race relations in Charlotte are positive. People are much more tolerant and respectful than we saw 50 years ago.”

One thing that can’t be denied is the city’s economic success. In the center of downtown stands the 47-story Hearst Tower, featuring Chinese marble and bronze grills from a 1920s Paris department store. It joins a skyline dominated by the towering headquarters of two financial giants, Bank of America and Wachovia, which have made Charlotte the nation’s second-largest banking center after New York. Surrounding the business district, lively new residential neighborhoods are going up—where white and black Charlotteans now live side by side. (The metro area is one of the most integrated in the country, reports the U.S. Census Bureau. Of course, in America, that’s not saying much.) Just as dramatic, on the block that once held the Woolworth’s of the 1960 sit-in, African American multi-millionaire Robert Johnson is building a $200 million stadium for his NBA team, the Charlotte Bobcats.

Inequities persist. Charlotte’s blacks still earn half of what whites do per capita and are three times as likely to live in poverty. “The bulk of financial wherewithal is all in white hands,” says Mel Watt, a Democratic congressman from Charlotte. “Marginally, gradually, we’re making progress, but it’s going to take a long time.”

And desegregation suffered a major setback in 1997, when a newcomer from California sued the board of education because his daughter was rejected by a magnet school for reasons of racial balance. The case eventually came before federal judge Robert Potter, a former antibusing activist. Potter reversed the Swann decision, and racial busing ended in 2002. Because the city still had many homogeneous neighborhoods, the result was an immediate lurch backward. “We have more schools that are identifiable as racially segregated than there were before the court ruling,” admits assistant school superintendent Susan Agruso. West Charlotte High School, held up in the ’70s and ’80s as a model of integration, is now 86 percent African American and only 5 percent white.

Which raises the question: can Charlotteans preserve the gains of the past 50 years, despite persistent challenges? Civil rights leaders are optimistic because of the respect Charlotteans have developed for one another since the days of Reginald Hawkins’s 1954 sit-in. A funny thing happened on the road to progress: in its efforts to project an image of tolerance, Charlotte actually came to honor diversity. “If you strive hard enough for appearance, sometimes you get substance,” says Tom Hanchett, staff historian at the Levine Museum of the New South in Charlotte. It’s that respect that offers hope, even when some of the substantive gains appear to be slipping away.

“I kick Charlotte’s behind every time I get a chance,” says former sit-in leader Charles Jones, now a 66-year-old attorney and neighborhood activist. “But I’m also proud of how we’ve grown. Charlotte is still struggling where the rubber hits the road, and it still stumbles and falls. But it gets up, shakes off—and continues to fight for a community where all God’s children are blessed.”