What can studies of pornography, prostitution, and seedy truck stops contribute to society?

Originally published in Discover.

Yorghos Apostolopoulos and Sevil Sönmez hope that their maps of trucker social networks will help stop the spread of sexually transmitted disease. Their research has come under attack from the Right.

YORGHOS APOSTOLOPOULOS WAS AT HIS OFFICE at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta last October when his red voice-mail light started glowing. When he picked up the phone, he heard a somber voice. “We need to speak,” said the caller, a program officer at the National Institutes of Health, which funds Apostolopoulos’s research on infectious disease. Her voice was drained of its usual casualness. “Don’t have any of your assistants call,” she said. “I want to speak with you personally.”

Apostolopoulos is a confident Athenian with a mop of salt-and-pepper hair and an intensity that belies his compact frame. With the NIH’s help, he has been pursuing a cutting-edge question about human behavior: How do networks of people—in particular, long-haul truck drivers—work together to accelerate the spread of an epidemic, even when some of them don’t know one another? Epidemiologists have long connected the spread of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa with truckers who get infected on the road and bring the virus home to their wives and girlfriends. But does the same hold true in the United States?

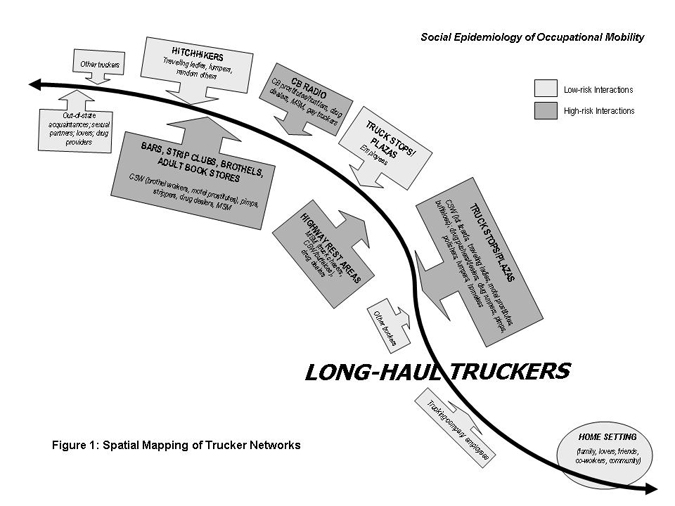

Working with a team of ethnographers, who study different cultures, Apostolopoulos and his partner Sevil Sönmez burrowed into the hidden world of truck stops, first in Arizona, then in Georgia. They began mapping the overlapping groups of people who come into contact with drivers: sex workers (sometimes called “lot lizards”), drug suppliers, cargo unloaders, and male “truck chasers,” who fetishize drivers. The researchers conducted extensive interviews to understand how truckers’ occupational stresses led to depression, drug abuse, and unprotected sex. And they have collected blood, urine, and vaginal swabs from drivers and members of their social network to map how infection travels from state to state.

Apostolopoulos considered his work essential, but not everyone agreed. That’s why the NIH officer was calling: Apostolopoulos’s name had topped an alphabetical listing of more than 150 scientists whose research was being challenged by conservative political activists. An 11-page list of NIH-funded grants was circulating around Capitol Hill and had been sent by a congressional staffer to NIH’s Maryland campus. Now the Emory research was being targeted by a group called the Traditional Values Coalition. “Wait until you see how angry the American people get when they discover… NIH [has] been using federal tax dollars to study ‘lot lizards,'” coalition director Andrea Lafferty declared in an open letter. “What plausible defense can be constructed for ‘investigating’ the sexual practices of prostitutes who service truckers?”

Many, though not all, of the grants on the hit list involved research into human sexuality. Each had been funded after rigorous peer review. But Lafferty raised a provocative question: Why do we study truck-stop sex workers? Or American Indians who consider themselves both male and female? Why survey the sexual practices of Mexican immigrants? Or hook women to monitors to quantify how their genitals respond to erotic movies? In short, what is the scientific value of delving into the forbidden?

AS ALMOST ANYONE WHO HAS FOLLOWED THE EXPLOITS OF BILL CLINTON or Pee Wee Herman knows, humans will place themselves at tremendous peril to satisfy themselves sexually. From an evolutionary standpoint, this makes sense. To pass our genes on to the next generation, we must engage in an activity that puts us at risk for disease and injury. Natural selection has endowed us with a hormonal system that sends us urgent psychological messages to have sex. It has also created considerable redundancy in how we receive sexual cues, making it hard for any single mechanism to shut down our libidos. “This is a very complex system, where the complexity is part of its evolution,” says Kim Wallen, an Emory University neuroendocrinologist.

Because it is intricate, there is much about sexuality that we don’t know, and we have few answers for many practical health questions. Why do people have unprotected intercourse, knowing they could become infected with a lethal virus? Why does female dysfunction remain resistant to treatments like Viagra? Trying to untangle these questions has required sophisticated research tools, and over the past decade a two-tiered approach has emerged.

The first involves probing the brain to understand the nature of sexuality. At Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, for instance, psychologist J. Michael Bailey and his former graduate student, Meredith Chivers, have discovered that men and women are fundamentally different in their arousal patterns. Bailey and Chivers fitted their research subjects with instruments designed to measure blood flow to their genitals, then showed them explicit two-minute video clips. The male participants responded predictably: Heterosexuals were aroused when they watched women having sex with women; gay men responded to watching men having sex with men. But women had a different reaction: All the film clips aroused them equally. “Their sexual arousal doesn’t seem to map onto their stated sexual preference,” says Chivers, who is now a fellow at Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

The implications of the Northwestern studies are enormous. For one, they start to explain why Viagra doesn’t work for women, even though it stimulates blood flow to the genitals: The relationship between physiological arousal and sexual function is complicated. The results also offer important information to psychotherapists whose clients are struggling with sexual issues. “Because we have a male model of sexuality, women who don’t fit that model feel they’re different or weird,” says University of Utah psychologist Lisa Diamond. The new findings may help clinicians whose female patients are confused by their erotic reactions to the “wrong” sex, for example.

The other research tier involves looking at networks of people rather than individuals. “Nothing occurs in a vacuum,” says Alan Leshner, head of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “The more we learn about the context of risky behavior, the more we can develop strategies for dealing with its consequences.” Epidemiologists now talk about syndemics—sets of interlocking afflictions (such as AIDS, violence, and substance abuse) that affect entire communities. By studying the social forces that bind these ills together, “you can really push the boundaries of public health,” says Dale Stratford, a medical anthropologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

NIH is funding researchers to look at risk behavior in many communities: Hispanic immigrant men who live thousands of miles from their wives, teens who cruise the Internet for pornography, Thai and Vietnamese women who work in San Francisco brothels. Each group presents specific health challenges. At the University of Washington, Karina Walters, an associate professor of social work, is studying American Indian “two-spirits,” who consider themselves a blend of male and female. (Many are gay or bisexual.) HIV is spreading through American Indian communities “on the scale of some small African countries,” she says, and men who have sex with other men are at particularly high risk. Walters has uncovered a syndemic of violence, substance abuse, and psychiatric problems among two-spirits and is now conducting extensive interviews to determine the underlying causes. She’s also exploring whether those with a stronger sense of their indigenous identities are less likely to participate in unprotected sex, drinking, and gangs.

Because much of this work involves interviews and observation rather than microscopes and petri dishes, it’s not always recognizable as hard science. It is science nonetheless. “Science is a way of obtaining knowledge through a systematic collection of data and testing of hypotheses,” says Christine Bachrach, chief of the demographics and behavioral sciences branch at the NIH’s National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. “In some studies, you draw blood and hook people up to machines. In other studies, you might need to map out the sexual ties that person A has with person B and that person B has with person C.”

Precisely this connect-the-dots method led to one of the most significant public-health breakthroughs of the past quarter century: In the early 1980s, epidemiologists studied the sexual and social connections among a group of gay men on both U.S. coasts who were developing fatal cases of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Their diagrams led them to realize that the cases were manifestations of an infectious disease spread by sexual contact—what we now call AIDS. Since then, network mapping has helped public-health officials control disease outbreaks throughout the United States. They learned, for instance, that tuberculosis was being spread in Kansas when crack cocaine users blew smoke (along with water droplets containing the TB bacterium) into one another’s mouths. This allowed TB-control experts to better identify people for screening and prevention. By identifying and targeting social networks, health researchers have also designed education campaigns that reduced needle sharing in Baltimore and unprotected anal sex in Louisiana and Mississippi and increased the use of modern contraceptives in Bangladesh.

“It’s not rocket science,” NIH’s Bachrach says. “It’s harder than rocket science, because what we see in the real world is the result of very complex forces. One of the challenges in observational science is sorting out what leads people to behave in the way they do.”

NIH OFFICIALS WERE DELIGHTED WHEN APOSTOLOPOULOS’S GRANT proposal arrived in January 2002. Except for a small project in the 1990s by Dale Stratford, little research had been done on American long-haul drivers and sexual health. “We knew from studies in Africa that truckers have played a role in the spread of HIV,” Bachrach says. “In the United States, the epidemic started on a different foot, so we never paid attention to the role of truckers. Yet truckers can bridge from one risk group to another, as well as bridging to the folks they’ve left at home.”

Apostolopoulos had come recently to health research. He earned his Ph.D. in sociology, studying the economic impact of tourism in his native Greece. That work spawned an interest in other mobile populations. Reviewing the literature, he discovered that few scientists had explored migration and health in any depth. This perplexed him. “Over a billion people are moving constantly in the world,” he says. “How can we study disease if we don’t study those people who are connecting high-prevalence and low-prevalence regions?”

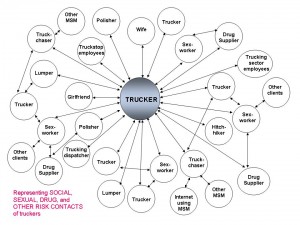

A long-haul trucker can be a part of a web of sexual and non-sexual relationships that spread disease, according to Apostolopoulos and Sönmez. (Click to enlarge.)

Apostolopoulos teamed up with the Turkish-born Sönmez, whose own doctoral work explored the social psychology of travel. Over the past five years, the two have become intellectual migrants themselves, studying mobile populations on three continents. They’ve looked at how sexual networks of semi-nomadic Ethiopians disseminate HIV in a country where famine and poverty have already weakened people’s immune systems. They’ve examined how sexually transmitted diseases spread among an estimated two million U.S. college students who travel to beach resorts during spring break. They’re now gearing up to study Eastern European women (and some men) who migrate throughout the more affluent European Union, engaging in what Apostolopoulos calls survival sex.

In 2001, while teaching at Arizona State University, Apostolopoulos and Sönmez turned their attentions to the 3.6 million long-haul truckers crisscrossing North America. For their preliminary fieldwork, they zeroed in on two truck stops. One was a hulking complex rising from a barren patch of desert 50 miles south of Phoenix. Across the road, sex workers came and went from two budget motels with peeling paint and weedy entranceways. The other, smaller and more urban, sat on a forlorn stretch of dust-covered road pocked by squat houses and occasional palm trees on Phoenix’s south side. There, women in short skirts solicited drivers, and homeless men slept in cardboard boxes at the side of a convenience store.

For a while, the researchers and their students observed quietly, eating french fries, conversing casually, and watching the hustle and bustle of the truck stops. “When you spend a lot of time, you kind of blend into the wallpaper,” Sönmez says. Over time, they began to parse out different populations. There were “polishers,” who earn $50 to $100 for shining the chrome on a truck. (Drivers are very proud of their rigs.) And “lumpers,” who load and unload freight. Truck-stop waitresses, who sometimes have sex with drivers. Drug dealers. Sex workers. Pimps. “Then we began to realize that they’re not existing in a vacuum,” Sönmez says. “Rather, they are constantly interacting among themselves. A sex worker may also run drugs. A polisher may do pimping. A polisher may also provide sexual services in certain circumstances, if his economic situation is desperate enough.”

By the time they finished their initial research, Apostolopoulos and Sönmez had mapped out 20 different populations that interact with truckers. “No one had ever described or even spoken about these networks before,” Apostolopoulos says. What’s more, the truck stops were not closed systems: A driver could carry infection from one way station to another, then home to his family. With only an initial study under their belts, though, the researchers couldn’t even start to quantify the potential consequences.

APOSTOLOPOULOS AND SÖNMEZ MOVED TO EMORY IN 2002. By then, they had secured $1.1 million from NIH to expand the study. They chose two truck stops in Atlanta, along with a gritty urban corridor where drivers congregate. All are located in depressed semi-industrial areas where government housing mingles with liquor stores and adult video stores, and where sex workers loiter near phone booths waiting for customers’ calls. At one site, a windowless gray nightclub—its parking lot perfumed by roasting meat from a nearby barbecue shack—features exotic dancers who sometimes sell sexual services on the side. At another, a patch of tall deciduous trees known as the jungle provides cover for covert sexual coupling.

Since September 2002, the Emory team has conducted extensive interviews—not just with truckers but with the entire network—to make sense of the social and sexual landscape. They have also tested drivers, sex workers, and other truck-stop denizens for HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia to see if the risky behavior in these sexual networks actually spreads disease.

So far, what they’ve uncovered is a syndemic that includes not only sexually transmitted infection but also drug abuse, violence, psychological distress, and depression. Some of the factors are relatively obvious: When truckers are away from home for 26 days a month, they get lonely and anxious and seek out sexual companionship. Other factors are buried more deeply in the social fabric. As the drivers came to trust the Emory researchers, some confessed that their dispatchers provide them with amphetamines to help them stick to their superhuman delivery deadlines. Amphetamines increase sexual arousal and lower inhibitions, so users were more willing to have unprotected sex. Truck-stop sex workers, desperate for cash, often permitted the behavior. “What do you do when someone refuses to use a condom?” one researcher asked a sex worker. “Well, I make sure I use baby wipes,” she replied.

Apostolopoulos and Sönmez also focused on another phenomenon ignored by scientific journals: male truckers who have sex with other men. There are Web sites and even conventions for truck chasers, who are drawn to the cowboy mystique of long-distance drivers. But their liaisons—often arranged over the Internet—look nothing like those in urban gay communities. “Many of these truckers identify as straight,” says Donna Smith, a researcher with the Emory team. “Because they define risk as being associated with identity—and because they are not gay—they believe they are not at risk. We’ve collected ethnographies in which truck chasers are asked by truckers, ‘Are you married?’ They perceive safety in a sexual encounter with another married man.”

When he began his research, Apostolopoulos had no idea his work would be held up for ridicule. In the summer of 2003, when a colleague sent him an e-mail message that four NIH-funded projects had barely survived a congressional defunding vote, he deleted it without much concern. “I assumed it was just a few unconventional studies,” he now says. “I didn’t pay attention till last fall.”

THE POLITICAL STORM HAD ACTUALLY STARTED GATHERING FORCE at the tail end of 2002, when a reporter for the conservative Washington Times called Michael Bailey of Northwestern at his small office overlooking Lake Michigan. The two men chatted for a while about the psychologist’s sexual-arousal study. Then the journalist blurted out his real reason for calling: “Isn’t that a little strange, that the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development is funding a study that uses porn?” On December 23, the Washington Times published an article questioning Bailey’s work, kicking off its crusade against NIH-funded sex research. (The psychologist sardonically calls the article “an early Christmas present.”) By New Year’s Eve, the Northwestern study had been ridiculed on two television talk shows, and soon Congress had joined in. “This flagrant frittering away of federal funds is borderline criminal,” declared Representative John Doolittle, a California Republican, the next summer. In July 2003, an effort to strip funding from four projects, including Karina Walters’s two-spirit study, failed on the House floor by a 212-210 vote.

Rather than settling the controversy, the close vote cranked it up. Last fall, the Traditional Values Coalition publicly challenged grants worth more than $100 million. “Some people may think it’s worthy to wire up female genitalia as they watch erotic video,” says Lafferty, the coalition director. “But dollars are scarce, and juvenile diabetes and heart disease need the funding.”

By most accounts, including Apostolopoulos’s, NIH has stood by its scientists, helping them draft explanations of their work’s scientific value. In January 2004, after ordering a comprehensive review of the institutes’ sexuality research, NIH director Elias Zerhouni sent his own letter to Congress. Biological research has done a great deal to improve the nation’s health, he wrote. But with half the country’s disease burden stemming from lifestyle, “the constant battle against illness and disease… has to include behavioral and social factors as well.” Critics, unconvinced, plan to press on. “The National Institutes of Health has been treated as a sacred cow,” Lafferty says. “No one is allowed to question it, and now we are. Researchers are freaking out because they realize the trough may dry up.”

Of course, this isn’t the first time science has collided with politics. Government-funded research is political by nature and designed to be accountable to taxpayers. Public pressure has sometimes helped refine science over the years, forcing researchers to treat women and minorities fairly during clinical trials, for instance, and improving the treatment of laboratory animals. Stem cell research and human cloning are legitimate topics of debate. “Science is stronger and more able to meet societal needs as a result of these conflicts,” says Daniel Sarewitz, managing director of the Consortium for Science, Policy, and Outcomes at Arizona State University in Tempe.

The incivility of the NIH debate, however, has promoted neither good dialogue nor good science. And it has had ugly ripple effects. “We have had scientists who have received death threats,” says Simon Rosser, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for HIV/STI Intervention and Prevention Studies. “Some have been professionally slandered. Some have been mocked by colleagues. Some have received calls at 2 a.m. saying, ‘Do you know where your children are?’ We’ve got enough of a problem trying to fight HIV without also having to fight threats, fear, and intimidation.”

Others worry that the current political battles might keep potential sex researchers from entering the field. Apostolopoulos, for one, acknowledges he has considered lying low until the political climate changes, though he continues to write proposals dealing with sexual behavior and disease transmission. He believes his submissions are strong enough to survive the meticulous peer-review process. “But in the back of your mind you think, ‘Are the reviewers going to be influenced by what has happened?'”

If that chill descends, Apostolopoulos hesitates to envision the consequences. “We could have a skyrocketing of disease,” he says after a long pause. “The ramifications could be explosive.”

SIDEBAR: Under Attack

RESEARCHER: Erick Janssen, Kinsey Institute, Indiana University

TOPIC: Mood, arousal, and sexual risk taking

WHAT CRITICS SAY: “It would be offensive to the majority of Hoosiers to think that in difficult budgetary times we’re spending money on the study of sexual arousal.” (Representative Mike Pence, Indianapolis Monthly)

WHY IT MATTERS: To stimulate different moods, Janssen showed his subjects clips from movies like Silence of the Lambs, then measured how they responded to erotic images. While most people lost their sexual appetites when depressed or anxious, 10 to 20 percent actually became more aroused. “That could be quite a dangerous mixture,” Janssen says. “It can affect people’s decision making in a way they later regret.” A deeper understanding of mood and arousal, Janssen hopes, will allow public-health experts to reach those who jeopardize their own lives while under stress.

* * *

RESEARCHER: Rebecca Seligman, Emory University

TOPIC: Psychobiology and spirit-possession religion

WHAT CRITICS SAY: “Any adult taxpayer would have difficulty moving studies of… spirit mediums… to the head of a list of projects for federal funding, which includes serious problems such as cancer.” (Traditional Values Coalition letter)

WHY IT MATTERS: Seligman found that practitioners of candomblé, a religion in which mediums go into trances, share two characteristics with people with psychiatric disorders: stressful lives and an inability to regulate arousal. Somehow, they avoid mental illness. Seligman’s work suggests a more sophisticated model of psychological health: “The dynamic between people’s cultural context, experience, predisposition, and physiological constitutions determines the outcomes they will experience. You can’t just say, ‘This mental illness is organic’ and automatically treat it by medicating it.”

* * *

RESEARCHER: Chris McQuiston, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

TOPIC: Gender, migration, and HIV risks among Mexicans

WHAT CRITICS SAY: “Are we going to research finding a cure for juvenile diabetes or the sex lives of Mexican workers?” (Andrea Lafferty, USA Today)

WHY IT MATTERS: Studying immigrants living in North Carolina, McQuiston found myriad trends that could hasten the spread of HIV on both sides of the border. The separation of husbands and wives isolates male immigrants, driving them to drink more and hire sex workers. When women do join their husbands, gender inequalities actually grow sharper in the United States than in Mexico, rendering many wives powerless to negotiate condom use. Effective anti-HIV programs need to address these issues. “Otherwise, it’s like wearing a sweater that’s one size fits all, and it really fits nobody,” McQuiston says.

* * *

RESEARCHER: Jianguo Liu, Michigan State University

TOPIC: Human and environmental interaction on a panda reserve

WHAT CRITICS SAY: “Shipping out more than $1 million to study the socialization of giant pandas in a nature preserve in China may not be the best stewardship of taxpayer money.” (Representative Joseph Pitts of Pennsylvania)

WHY IT MATTERS: “Pandas had nothing to do with this study,” says Christine Bachrach of NIH’s National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The simplistic models used to forecast the environmental impact of population growth are often wrong. Using a Chinese panda reserve where humans also live, Liu is testing a more nuanced model. The reserve’s extended-family households have been breaking into smaller households over the past three decades. More homes, which in turn means more fuel-wood consumption. How does that affect forest resources?

* * *

RESEARCHER: Timothy Guinnane, Yale University

TOPIC: Irish fertility at the turn of the 20th century

WHAT CRITICS SAY: “That doesn’t pass the straight-face test.” (Andrea Lafferty, CNN)

WHY IT MATTERS: “Changes in fertility levels have a dramatic impact on society,” Bachrach says, affecting everything from couples’ happiness to the solvency of Social Security. One way to understand why these levels rise and fall is to look at historical trends. Ireland underwent a well-documented fertility transition in the early 20th century, making it a good study model.

* * *

RESEARCHER: Tooru Nemoto, University of California at San Francisco

TOPIC: HIV risk reduction among Asian sex workers

WHAT CRITICS SAY: “Wouldn’t the money be better spent on a program to end [prostitution], finding these women the care they need and helping them find legitimate jobs?” (Representative Joseph Pitts)

WHY IT MATTERS: Legal or not, commercial sex plays a critical role in the spread of HIV. “To intervene, we must first understand how to prevent transmission by sex workersof different ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and these people are hard to reach,” explains NIH director Elias Zerhouni. Nemoto’s study tests culture-specific strategies on Vietnamese and Thai immigrants, who have been largely ignored in the past.