The hospital couldn’t save Jack’s life. But hospice gave him something to live for.

Originally published in AARP The Magazine.

JACK SMITH LOOKED UP FROM THE EVENING NEWS to see two old buddies bounding down the steps to the basement den of his northeast Philadelphia home. At once his tired face broke into a wicked smile. “There’s beer behind the bar,” he called out, pointing to the refrigerator full of Meister Braus. Then he turned to his daughter, Danielle Carpenter. “Get me a drink,” he said good-naturedly. “A whiskey and water. No ice.”

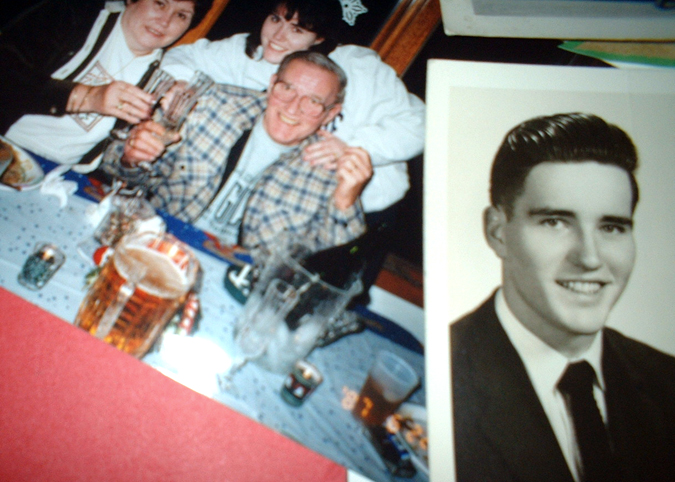

Brews in hand, the two men plopped on the sofa, all shouts and laughter. This was where Jack held court: a cavernous clubhouse for overgrown boys, its low ceiling plastered with triangular pennants. Notre Dame. Chestnut Hill College. San Jose Sharks. Philadelphia Eagles. A glass case displayed an “Archie Bunker for President” mug, and laminated certificates honored the Cardinal Dougherty High School soccer team, which Jack had coached during its championship streak in the 1970s. Jack’s friends were guys whose histories, like his own, were intertwined with Philadelphia’s Catholic schools. Florian Kempf had been one of his star players — he’d gone on to kick for the Houston Oilers. Father Ron Ferrier, a science teacher at Dougherty, had presided over the weddings of both of Jack’s daughters.

More recently, Father Ferrier had administered last rites to Jack. But instead of succumbing to esophageal cancer, Jack had come home from the hospital, climbed into his blue terry cloth robe, cranked up the space heater, and opened the basement to visitors.

As the men settled into drinking, Jack launched into a well-worn story about the time a much younger Danielle came home with a friend, plastered for the first time. “Those two idiots drank a fifth of whiskey, then proceeded to throw up all over me,” he exclaimed as his friends howled with laughter. Jack recounted how he ordered Danielle to change her clothes — “and goddamn it, she comes back in her goddamned St. Huber’s school uniform!” Jack loved to swear, even in front of priests.

Everyone in the room knew Jack was dying. But the retired coach and maintenance supervisor had decided he wouldn’t spend his final weeks in the hospital chasing an unlikely cure. Instead, he would make his remaining time as joyful as possible. He’d settle into his basement. He’d surround himself with family and friends. Back when Jack and his wife, Peggy, were engaged, they would listen to the Beatles sing “Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I’m 64?” Jack’s 64th birthday was coming up, and he intended to be needed and fed — at home.

What made this scenario possible was the hospice program at Philadelphia’s Fox Chase Cancer Center, whose care team focused on maximizing Jack’s comfort. Nurses, an aide, and a social worker visited regularly, making sure that all problems — pain, nausea, sleeplessness, even despair and family grief — were addressed. So were the tasks of daily living, like bathing. That freed Jack to do what he really wanted: sit in his den with his loved ones, talking about old times.

“I tell our families that the goal of hospice is to help a patient live — underline live — as best they can with their illness,” says Debbie Seremelis-Scanlon, hospice liaison for the Fox Chase program and a registered nurse. “If you’re having a good day, great. If you’re having a bad day, call us and tell us what’s making it bad.”

That’s a revolutionary concept in this country, where death too often comes in a hospital room filled with machines and tubes — desperate and often futile attempts to eke out a few more weeks. Knowing no alternative to this decades-old model, many patients believe hospice is a euphemism for giving up treatment — and hope. “The first question I always ask is, ‘What’s your understanding of what’s happening now?’ ” says Fox Chase hospice social worker Rhoda Goldstein. “A lot of times they say, ‘They sent me home to die.’ Well, maybe they sent you home to live.”

A HUNDRED YEARS AGO, PEOPLE TYPICALLY DIED at home, of epidemics, infectious diseases, and injuries. That changed with the 20th century’s staggering medical advances. Doctors grew excited by the prospect of keeping sick patients alive longer with medication and surgery. Lives indeed grew lengthier — but in the process death in America was transformed into an institutional and technological affair. “People were dying in the hospital; they were dying in circumstances where the process was hidden and painful, and suffering was justified by the fight to cure whatever was causing the death,” says Linda Emanuel, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Buehler Center on Aging at Northwestern University. “Denial was so great that patients and families ended up suffering physically, socially, psychologically, and spiritually.”

It was the U.S. Civil Rights Movement that set the stage for a reexamination of how we die. As Americans learned to question authority, they began to doubt the doctor-driven high-tech model. Some looked to London, where in 1967 Dame Cicely Saunders had set up St. Christopher’s Hospice, a residence for the terminally ill that focused on relieving pain and other symptoms rather than trying to prolong life. Visitors to St. Christopher’s were surprised by what they found. “Instead of a terminal-care or ‘death house’ environment with narcotized, bedridden, depressed patients, I found an active community of patients, staff, families, and children of staff and patients,” reported one doctor in a 1975 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The first U.S. hospice opened in Connecticut about that time, but it wasn’t until recently that the American movement took off. In 1992, U.S. hospice programs served 246,000 people. Ten years later, the figure had reached 885,000. Today, even though most hospice patients remain in their own homes, the original principle is the same: a hospice team focuses on “palliative care,” working to make the patient’s days as symptom-free as possible. Nurses dispense medication for pain control. Social workers help patients and their families prepare for the end of life. Clergy members provide spiritual counseling. Volunteers fill a variety of niches, from sitting with patients to helping clean and maintain their property. Some hospices offer massage or music therapy; nearly all provide bereavement services for relatives. There’s even the possibility of expensive medical procedures — blood transfusions, chemotherapy, radiation — as long as the purpose is to control pain, fatigue, or shortness of breath. In Jack’s case, care was covered by private insurance — most policies have a hospice benefit — though the majority of patients are covered by Medicare, and they never see a bill. Benefits are portable: they apply to wherever the patient calls home, including a relative’s house or an inpatient facility.

The goal is to allow patients to live fully, even during their final weeks. “If what matters to you is to go fishing, for heaven’s sake, go fishing and figure out how to take the oxygen tank to the end of the stream,” says Joanne Lynn, M.D., director of the Washington Home Center for Palliative Care Studies in Washington, D.C. Many hospice patients use the time to review their lives, mend broken relationships, and find spiritual peace. “It’s trying to undo what Descartes did by separating the mind and body,” says Michael H. Levy, M.D., Ph.D., medical director of the Fox Chase hospice. “It’s not just DNA that’s sick; it’s the human being.”

WHEN FOX CHASE’S DEBBIE SEREMELIS-SCANLON met the Smiths for the first time in November 2001, she found a family whose high emotional idle had cranked up to a frantic rev. At 63, Jack had already completed treatment for lung and bladder cancer with few complications. The first time, after his surgery, he threw a “goodbye, lung” party and kept right on smoking. But this new illness, a rare soft-tissue sarcoma first discovered in his esophagus, had taken a deeper hold on his body. His life had become a revolving door of chemo treatments and hospital discharges, and he dreaded each new round. He looked like a skeleton. He had pneumonia. He had trouble swallowing, and his feeding tube leaked. When he grew delirious and the hospital staff tied him to his bed, his family had had enough. “I felt so angry over what they did — the hole in his stomach, this bag of bones that looked nothing like my father,” says Melissa Kuchler, the younger of Jack’s two daughters.

He wasn’t getting any better, nor would he. Still, when Seremelis-Scanlon suggested hospice, the family was torn. Melissa and her brother, Matt, wanted to stop the treatment and bring him home. “I wanted not one more needle put in that man,” says Melissa. “Not one more ounce of pain.” But Danielle, a medical assistant in the oncology department of another hospital, wasn’t ready. “I just didn’t want him to die,” she says. “I said, ‘There’s got to be something else you can do.’ I thought if we went on hospice, there was no turning back, like we were saying it’s okay to die. It’s not okay to die.”

For her part, Peggy Smith didn’t really understand what the nurse was suggesting. “To me, hospice was when you admitted you were dying and that was a final decision,” she says. “I thought they would check up on him occasionally and take his blood pressure.” Delicately choosing her words — she saw the family’s frustration — Seremelis-Scanlon explained to Peggy that the program was far more comprehensive and that Jack could change his mind anytime. At this, Peggy did a double take. “Did you say that if he feels better, he can resume treatment?” she asked. “Absolutely,” the nurse said.

Jack himself made the final decision. “I’ve had enough,” he declared.

Immediately, hospice went into motion. A hospital bed and a small oxygen machine arrived at the Smiths’ home the day of his enrollment. A team of experts began meeting weekly to discuss Jack’s care. They brought him morphine for pain. A social worker talked with the family about how to explain death to the grandchildren. Every weekday, an aide came to bathe Jack, wrapping him in towels to keep him warm. She massaged his back, changed his sheets, chatted with him. “It was like she was caring for someone in her own family,” Melissa says.

As Jack rested at home, his pneumonia cleared up and he began to return to his old self. For a while he was able to climb stairs. The family celebrated Thanksgiving together, then Jack’s birthday. Friends visited him in the basement hideaway, where they’d smoke and reminisce — “like a living wake,” his wife says. And Jack, a man not usually given to introspection, began settling up his emotional debts.

“My father totally opened up and changed,” Danielle says. “He would say things just to get them off his chest — family secrets — because he didn’t want anything left unsaid.” For the first time, Jack regretted aloud that he and his brother didn’t have a closer relationship. He wished, too, that he could have been a better father. And he reflected on what a homebody he had been, even when Peggy was itching to go out. “I wish I could have done more things with your mother instead of giving her a hard time,” he confided to Danielle. Still, whenever he saw one of the women in his family break down, his toughness came back to the fore. “Knock that off,” he’d say. “What the hell you crying for?”

“That last month of his life,” says Peggy, “was incredible.”

JACK SMITH WAS LUCKY, both to get into a hospice program and to reap its benefits for a full month. For all of the hospice movement’s growth, it still reaches only one in four dying Americans, and in many places considerably fewer. A terminally ill patient in Portland, Maine, for example, is less than one tenth as likely to use hospice as someone in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. There are many reasons for these variations. Florida has a state licensing process that encourages large hospice organizations with the resources to advertise, do community outreach, and build relationships with doctors and hospitals. Maine has no similar process.

Ironically, when it comes to access, big cities aren’t always the best. New York, for example, has some of the lowest hospice rates in the country. “It has something to do with a very academic and highly advanced health-care system,” says Carolyn Cassin, director of Jacob Perlow Hospice at New York’s Beth Israel Medical Center. “There’s more health care here than anyone can consume.” Big-city doctors are so enamored of the medical razzle-dazzle available to them that they often don’t refer patients to hospice. “In 2002, 12.8 percent of patients who died of terminal illnesses in New York were assessed suitable for hospice,” Cassin says. “Shameful! It should be up in the 60 percent range.”

Even for those who make it into hospice, there’s a trend toward shorter enrollments. In 1992, 21 percent of all hospice patients died within one week of admission; a decade later, the figure had climbed to 35 percent. “One of the saddest things is when we have a patient who could have benefited from the hospice program for several months — but by the time the doctor makes the referral, they only live three or four days,” says psychologist Dana Cable, Ph.D., board president of Maryland’s Hospice of Frederick County. “That’s not enough time to get them into pain control and to work with the family to help them cope with death.”

WHY ARE SO MANY PEOPLE STEERING CLEAR of hospice or waiting until their final days? Like Peggy Smith, many relatives equate hospice with “giving up.” Or like Danielle Carpenter, they don’t want to forfeit that one last shot. But patient and family attitudes are only a small part of the problem: There’s a whole set of barriers, from physician training to federal-funding formulas, that combine to depress the level of hospice use in the United States.

Leading the list of obstacles are doctors themselves. They control a medical system that is focused on curing disease, not comforting the ailing. Today’s physicians control medical school curricula, so tomorrow’s doctors receive little or no training in end-of-life care. “Only when the patient is days before dying does anyone think, oh, maybe we should call hospice,” says Betty Ferrell, Ph.D., a research scientist at the City of Hope National Medical Center in Los Angeles. “Physicians need to learn how to say, ‘You know, your mother has had a rough last few months. I, like you, am hopeful. However, I’d like us to consider what her care might be if she continues on this course.'”

While many medical schools have started teaching palliative care, many experts agree they still have a long way to go. Even after a doctor graduates, the opportunities to learn about end-of-life care remain sparse. Says Fox Chase’s Levy: “Most doctors aren’t trained in how to sit down with a patient and talk about the difficult realities of what science has to offer.”

Physicians, of course, are human. Telling patients that they’re dying is a gut-wrenching process, and many doctors will postpone the conversation as long as possible. So even those doctors who are well-trained find themselves faltering. “Some patients become these sequoias, the pillars of our clinical practice,” says Christopher Daugherty, M.D., a clinical oncologist and medical ethicist at the University of Chicago. “You become more hesitant with those patients to disclose bad news. It happened to me yesterday: One of my patients with advanced leukemia was visiting the hospital, and I knew that I needed to see her. There was a perfect opportunity to say, ‘There is no more therapy I can give you.’ But I didn’t have the guts and fortitude. Who wants to give bad news?”

EVEN IF THESE HUMAN IMPEDIMENTS were suddenly overcome, the federal government has created a system with yet more obstacles. The first is cost. The Medicare hospice benefit, which covers the vast majority of patients, was passed during the Reagan administration, which emphasized cuts in domestic programs. Reagan budget director David Stockman agreed to support the hospice benefit — on the condition that strict limits were placed on reimbursement.

Today, Medicare typically reimburses programs at a flat daily rate of about $125 per patient for routine home care rather than covering all costs. That’s fine for those who need only periodic nurse visits and inexpensive medicine. But what about someone who requires a blood transfusion to combat fatigue? Or needs intravenous morphine for pain relief? What about a patient who lives alone and needs intensive nursing? Those services cost more than $125 a day. Some large programs can absorb the added cost, but others need to turn away pricier applicants. The $125 limit particularly frustrates rural hospices, which have staggering transportation costs, and small hospices, which don’t benefit from economies of scale. “If you don’t have enough patients, you don’t receive enough federal money to run the office and hire the staff,” says Levy.

Even more of an obstacle is Medicare’s requirement that hospice patients have six months or less to live. If a patient outlives the diagnosis, hospice funding continues. But if too many patients outlive their diagnoses, doctors worry they’ll be busted for Medicare fraud. In the mid-1990s, the feds began studying medical records in Puerto Rico, where patients were tending to live beyond the six-month limit. The investigation spread to the U.S. mainland, and even though it didn’t result in widespread prosecutions, it left a chilling effect on other physicians. As a result, to play it safe, doctors often wait until a patient is right at death’s edge before making a hospice referral.

“The federal government has drawn a line in the sand,” says Cassin of Beth Israel. “I can’t take the patient who’s dying of Alzheimer’s, who is lying in a nursing home, and the family is desperate for hospice. I can’t sign her up till she’s almost comatose — because until then, I can’t say she’ll die within six months.”

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of Medicare funding is that, by law, patients must give up all curative treatments in order to claim the hospice benefit. “The government will pay for you to live as long as you can, or to die as comfortably as you can, but not both,” says David Barnard, Ph.D., an ethicist and palliative-care specialist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. “That’s a ridiculous bureaucratic distinction that makes no sense in the real world. Everybody who has a life-threatening illness wants both to live as long as they can and to die as comfortably as they can.”

This is a terrible choice. Advocates say that lifting Medicare’s either/or restriction would dramatically increase hospice access. Patients wouldn’t feel forced to choose between accepting death and pursuing life. Doctors, too, would be more willing to refer patients to hospice, because they wouldn’t have to give up conventional therapies at the same time. Although the jury’s still out on cost, such a system might actually save money, because patients would feel better equipped earlier on to phase out expensive and futile treatments. More people would have access to the attentive care that Jack Smith had as he approached the last few days of his life.

THE PHONE RANG AT 2:30 A.M. on December 12, 2001, in Debbie Seremelis-Scanlon’s home in northeast Philadelphia. It was Melissa Kuchler, reporting that her father had taken a turn for the worse.

For several days, Jack had known his life was coming to an end. So had his family, who had moved him upstairs and were scrambling to get the Christmas decorations hung while he could still appreciate them. The holiday lights were Jack’s bailiwick: each year he would spend the Feast of the Immaculate Conception turning the house into a neighborhood spectacle. Drivers would slow down on the Smiths’ block to catch a glimpse of the joyful excess.

This year, weakened, Jack couldn’t do the honors, so his family took over. For the mantel, Peggy chose simplicity: a Hummel Nativity scene offset by winter greens and white lights. “That is so beautiful,” Jack said. “I think that is the nicest I’ve ever seen the mantel.” Danielle came over to decorate the tree with her niece. Jack forewent the Eagles game on TV, sitting back instead and watching his daughter and granddaughter animate the living room with holiday color. When Danielle pulled out the five-pointed white star that topped the tree, one of the tips broke off. “I’ll pick up another one,” she promised.

The next day, though, the star-shopping plans got put aside when Jack suffered a setback. Walking to the commode, he suddenly collapsed. Peggy caught him as he fell, and then called Melissa and the hospice for help. “That was his last lucid time,” she recalls. “That’s when I knew it was over.”

For the next two days, relatives came to visit the Smith home. Some gathered around the kitchen table as Peggy kept the coffee brewing. Others sat next to Jack’s bed as he slipped in and out of consciousness. Father Ferrier came by to administer last rites — again — but the solemnity was broken when Jack rallied and told the priest a racy joke. Grandchildren ran around everywhere. When the house finally emptied out Tuesday night, Peggy sank into the living-room couch, too tired to worry about anything but slumber. Danielle slept fitfully in a dining-room chair until her sister ordered her upstairs to their parents’ empty bedroom. Melissa snoozed on the recliner. Matt commandeered his father’s basement sofa. “We just wanted to be close to him,” Danielle recalls.

Then, at 2:30, Jack’s breathing grew so rattly that the sound carried upstairs and jolted awake his elder daughter. Danielle hurriedly roused her mom. “We need to get up,” she said urgently. “This is the end.” Peggy pulled herself from her delirious sleep to find her three children agitated and uncertain about what to do. “We were petrified,” Danielle recalls. “How long was it supposed to take? Do we have an hour? Is it minutes? I remember just shaking. I didn’t even want to go to the bathroom.”

Seremelis-Scanlon lived only a mile away, and she arrived at the house within minutes. She recognized the rattling sound as an inability to swallow properly. In the hospital, Jack might have had his secretions aspirated mechanically, an invasive and noisy process. But with hospice, comfort was paramount. Seremelis-Scanlon gave him some medication to reduce his secretions, pain, and agitation. Gradually, he relaxed.

“Come on now, let’s let him rest,” Seremelis-Scanlon told Jack’s children, who were crowded around their father. “Sometimes it’s harder for them to let go with their family in the room.” So the kids moved into the living room, where their mother was already sitting on the edge of the couch, smoking. Peggy rose to fix coffee, and as she walked toward the kitchen she passed her husband. She stopped to look at him, then sat down at the edge of his bed.

“Jack, it’s okay,” she said, stroking his head. “If you want to go, it’s time. I’ll be okay. I’ll take care of the kids. Everybody’s all right. I love you. I know you’re afraid. Let the Blessed Mother take you. Go be with your mom, your dad, your brother, and be at peace.”

Softly, she began to sing a favorite song from their long-ago days as young sweethearts:

When I get older, losing my hair, many years from now

Will you still be sending me a valentine, birthday greetings, bottle of wine?

If I’d been out till quarter to three, would you lock the door?

Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I’m 64?

Jack’s breathing grew calmer. Peggy sang some more. And then, peacefully, he just slipped into death. “There was no sound when he passed away,” says Seremelis-Scanlon. “It was just a breath. And a breath. And no breath.”

He had just, 12 days earlier, celebrated his 64th birthday.

A few hours before dawn, as the hearse pulled away, Danielle walked outside and gazed up into the night sky. “Come here,” she called to her family. “Look at that!” There, directly above the Smiths’ house, flickered the brightest of white Christmas stars.

“THOSE WERE THE BEST TIMES I ever had with my father,” says Melissa, sitting at her mother’s kitchen table a year and a half later. “His mind was able to clear from all the medications. It put pride back in him. He could hold regular conversations. It restored his dignity.”

Today, Melissa thinks of her father’s last weeks not with unmitigated grief but instead with a stew of emotions that includes no small amount of joy. “Without that time in hospice, I don’t think he would have been able to let go,” she says. She contemplates the misconceptions her family held in November 2001 and how grateful she is that they didn’t deny themselves the opportunity for a meaningful final month together. “I thought we were going to sit in this house and have a death watch,” she says. “It was so much more than that.”

SIDEBAR: Choosing a Hospice

First, consider your options in advance so you aren’t making decisions during a stressful time. For information, call 703-837-1500 or go to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization to find a provider. A full list of questions to ask is available on NHPCO’s website, but here are a few:

- How many patients are assigned to each hospice staff member?

- Does the hospice staff regularly discuss pain and symptom control with patients and their families?

- Are expensive symptom-relief treatments like blood transfusions and radiation available?

- Are all expenses covered by Medicare or private insurance?

- How does the hospice program help family members cope with the patient’s death?