In his new autobiography, Jesse Helms sees himself as a humanitarian—not a racist supporter of brutal right-wing regimes who turned obstructionism into a foreign policy.

Originally published in Indy Week.

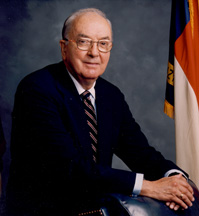

I’VE ONLY MET JESSE HELMS ONCE. I was profiling him for two national magazines during his 1996 Senate race, and for two days I shadowed him around the U.S. Capitol. He looked like a fragile, senescent bear and spoke with a mumble that the average Northerner might have had some trouble deciphering. He was harder than most to track down—but finally, as a Senate Foreign Relations Committee was breaking up, I got my five minutes with the Republican icon. “This isn’t about Bosnia, senator,” I started.

I asked Helms a question about the “homosexual lobby”—one of my clients was a gay magazine—and listened as he stumbled and evaded and lost his own train of thought. He asked me to repeat the question. I have a stutter, and mid-sentence I hit a block. “I can’t understand you,” the senator told me, then swiveled around and walked away.

It was easy at that moment to dismiss Helms as a doddering lightweight with stooped shoulders and an ineffectual streak of meanness. It was harder to see him for what he really was: a powerful national figure who ruthlessly (and, too often, effectively) pursued an obstructionist right-wing agenda.

During his three decades representing North Carolina in the Senate, Helms befriended human-rights abusers around the world; stalled important treaties and appointments; and launched spirited attacks on civil rights, AIDS funding, and legalized abortion. He helped mastermind a brilliant fund-raising machine, and had his fingers in everything from black-voter intimidation to a veiled threat against President Clinton’s life. His name was the first thing strangers mentioned, usually with derision, when I told them I lived in North Carolina. Yet he also won all five of his senatorial races, trading in on white racial resentment, Christian conservatism, and an avuncular, countrified style.

Now, just before his 84th birthday, Helms has finally decided to share his story. This month, Random House is releasing the former senator’s Here’s Where I Stand: A Memoir. Its 36 chapters offer no introspection, no sense of fallibility—not even the basic elements of good storytelling. But we do get 300 pages of Helms’ own words, or perhaps those of a second-rate ghostwriter. In that sense, Here’s Where I Stand is an important historical document about one of America’s most important 20th-century political figures.

It is also a curious exercise in political whitewash. For a senator whose very strength lay in his combative style, Helms has managed to portray himself as a lover of all humanity, from deceased Democrats Paul Wellstone (“a courageous defender of what he believed”) and Hubert Humphrey (who allegedly told Helms “I love you” on his deathbed) to the entire Jewish people, “who prepared the way for the true Liberator of all mankind, Jesus Christ.” In fact, he writes, the Jews were one of two peoples whose histories inspired “the freedom Americans enjoy today.” The others, of course, were the Anglo-Saxons.

HELMS SPENDS THE FIRST EIGHT CHAPTERS of his autobiography outlining his life before the Senate, and they paint a Mayberryish picture of small-town North Carolina during the Jim Crow era. “My boyhood days were golden,” he says: He grew up in Monroe, 25 miles from Charlotte, the son of plain folks who took in hobos in the middle of the night and fed them “Mama’s biscuits” slathered with “generous helpings of fatback.” His father was a police chief who overlooked moonshine stills, eschewed the word “nigger,” and reconciled a local grocer (“Mr. Bob”) with the burglar who had stolen some dried beans the night before. “When the stolen goods were offered to Mr. Bob, he hugged this man who had robbed him,” Helms recounts in one of many aw-shucks tales from his childhood.

So perfect were those days that even the high-school principal, Ray House, borders on sainthood: “If it were possible to assemble all the young people who went to school under him and take a poll, every one of them would say ‘I loved him.'”

Helms spends precisely two paragraphs on his political awakening. He attributes this conversion to his father-in-law, Jacob Coble, who sold shoes wholesale and helped him understand “how the strength of a free-market system is interwoven with the true strength of our democracy.” Helms’ first up-close experience with electoral politics came during the 1950 Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate. The incumbent, Frank Porter Graham, was the ex-president of UNC-Chapel Hill and, in the words of former News & Observer publisher Jonathan Daniels, “the single most important human force for enlightenment in the state.” Challenging Graham was Willis Smith, a retired state legislator whose campaign accused the incumbent of being a race-mixer and communist sympathizer. “White people, WAKE UP,” said one handbill. “Do you want Negroes working beside you, your wives and daughters in your mills and factories?” Another handbill featured a doctored photograph of Graham’s wife dancing with an African-American man. Radio ads proclaimed, “Do you know that 28 percent of North Carolina’s population is colored?” The crude tactics worked: Smith eked by Graham in the runoff, then went on to win the Senate seat in the general election. Helms later became Smith’s administrative assistant.

For more than a half-century, Helms has remained silent about the Smith campaign, even though he’s been dogged by insinuations that he was behind the inflammatory handbills. In his book, he tries to set the record straight. Both candidates were “fine gentlemen,” he writes, and Smith in particular was the “kindest man imaginable.” But Helms insists he had no official role in the 1950 campaign. Working as a radio reporter for Raleigh’s WRAL, “I sat in on some of the staff meetings as an observer,” he writes. He also admits producing some 10-second ads urging Smith to call for a runoff after placing second in the primary. But Helms also wants to make something clear: He was neither a member of the Smith campaign nor the creative genius behind the altered photo.

Others remember differently. In the 1986 book Hard Right: The Rise of Jesse Helms, journalist Ernest Ferguson interviews James “Pou” Bailey, a retired judge and close Helms friend who also worked on the Smith bid. Helms was “up to his neck” in the campaign, Bailey said. “I don’t think there was any substantive publicity that he didn’t see and advise on.” Ferguson also interviewed a retired N&O advertising manager, now deceased, who claims to have watched Helms wield the scissors that doctored the photo.

Whether Helms is setting the record straight or obfuscating it further is a matter of he-said-she-said. Read deeper into Here’s Where I Stand, though, and the whitewash grows considerably more evident. Two chapters later, Helms describes the job that catapulted him to statewide fame and launched his political career: his 12 years as an on-air editorialist for WRAL-TV. Throughout North Carolina, he tells us, “Everyone would gather around the television after dinner to hear the news and then the editorial… In many cases no one was allowed to speak until the editorial was finished.”

What Helms manages not to tell us, though, is the content of those editorials. He quotes a bland one on federal housing programs, and a mournful one about the Kennedy assassination. (“The manner of his death leaves America standing naked as a symbol of civilization mocked.”) What he doesn’t say is that the 2,751 editorials were based in some of the most venal bigotry of the times. “Are civil rights only for Negroes?” he asked in 1963. “White women in Washington who have been raped and mugged on the streets in broad daylight have experienced the most revolting sort of violation of their civil rights. The hundreds of others who had their purses snatched last year by Negro hoodlums may understandably insist that their right to walk the street unmolested was violated.” In his five-minute editorials, Helms condoned lunch-counter segregation; said civil-rights protesters were “no less an affront to society” than the Ku Klux Klan; and accused civil-rights marchers of participating in “sex orgies of the rawest sort.” He also insisted that four Alabama Klansmen who murdered a Detroit woman in 1965 were responding to “deliberate provocation” by Martin Luther King Jr. and President Lyndon Johnson. If Helms feels any remorse for inflaming racial tensions in North Carolina during the 1960s, he reveals none of it in his new autobiography.

In fact, he still justifies his opposition to civil-rights laws. “Many good people who supported the principle of progress for everyone could not agree to the destruction of one citizen’s freedom in order to convey questionable ‘rights’ to another,” he writes. “They believed forced social engineering was hazardous to the freedom we all deserve.” By polarizing the races, Helms writes, the civil-rights movement constituted a “new form of bigotry.” But he also wants us to know that he himself is not a racist. As proof he offers his “friendship”—more like friendly banter—with one of the Capitol’s black elevator operators.

HELMS FIRST RAN FOR THE SENATE in 1972, shortly after he switched his registration to the GOP (at the behest, he says, of his young daughter). He claims to have been a reluctant candidate: “I just didn’t see myself as having any great personal appeal to the voters.” But he says he was “inundated” with pleas, which convinced him to challenge Congressman Nick Galifianakis for the Senate seat.

In Here’s Where I Stand, we read very little about the ’72 race, except that it was a “real doozy” and that Helms sometimes arrived at a campaign stop to find “three ladies and a plate of cookies waiting for me.” Perhaps he glosses over the race because it contained echoes of the Graham-Smith battle 22 years earlier. The Republican’s slogan was, “Elect Jesse Helms: He’s One Of Us!”—a not-so-subtle reference to the Durham-born Galifianakis’ Greek ancestry. Helms also created a bogus physicians’ group that attacked the Democrat for being soft on drugs, and coined the word “McGovernGalifianakis” in his newspaper ads. Though the autobiography omits these details, Helms does take the time to praise Galifianakis’ parents as “brave immigrants” and to dismiss the “false charge that we made our opponent’s proud heritage an issue.”

In a year that President Nixon trounced George McGovern in North Carolina, Helms sneaked past Galifianakis by 120,000 votes. His subsequent campaigns were aided by his own Raleigh-based National Congressional Club, at one point the nation’s richest political action committee and one of the most scandal-plagued. Those later races were equally brutal. Helms’ 1990 bid against former Charlotte Mayor Harvey Gantt featured a last-minute TV ad in which a pair of white hands crumpled a rejection letter. “You needed that job, and you were the best qualified,” said a voiceover. “But they had to give it to a minority because of a racial quota. Is that really fair?” In his new book, Helms says he was responding to legislation, passed by Congress and vetoed by President George H.W. Bush, that would have increased available remedies for job discrimination. Helms mischaracterizes it as a “quota bill” and now claims race had nothing to do with his objections. “Minority classifications were not limited to race,” he writes.

Of course, Helms also denies that this 11th-hour advertising blitz had anything to do with the fact that Gantt, a charismatic and successful architect, happens to be African American.

THE MOST DISQUIETING SECTION of Here’s Where I Stand is Helms’ description of his 30 years in Washington. When he arrived, he writes, the Senate was “a sort of gentlemen’s club” of Democrats and moderate Republicans. “They didn’t want to make any waves; I wanted to drain the swamp,” he writes. Then, for the next 200 pages, the former senator gives us a toned-down rendition of how he drained the swamp: Helms Lite.

Take foreign relations. Helms describes his institutional archnemesis, the State Department, as a bunch of “do-as-we-please bureaucrats” and mentions that his staff developed “alternative resources for information.” This “fact-gathering,” as he calls it, uncovered important information, including an alleged secondhand link between an obscure United Nations agency and the North American Man/Boy Love Association. “Our State Department was not aware” of this connection, he writes. “The department claims they were horribly embarrassed by this episode, as they should have been.”

Was this really the essence of Helms’ foreign relations operation? A few fact-checkers who ferreted out pedophiles with vague quasi-governmental connections? Not exactly. As a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Helms ran a “shadow State Department” that sent staffers all over the globe, gathering intelligence from Latin America, southern Africa, Taiwan, South Korea and Western Europe. He built a network of right-wing political and business leaders, along with anti-communist exiles from Cuba and Central America. Conservative organizations at home and abroad funded many of these adventures.

To what end? Demurely, Helms says that he was trying to separate the “good guys” from the “bad guys” and to ferret out communism wherever it lay. (Apparently it lay everywhere: “Communism came over on the Mayflower,” he writes, disparaging the Pilgrims’ efforts to share the wealth in the Plymouth colony.)

So, who were Helms’ “good guys”? This is where Here’s Where I Stand again grows silent. The former senator fails to mention that, particularly during the ’80s, he built some rather shady alliances. Among his friends:

- The Mozambican National Resistance, or Renamo, a rebel group sponsored by South Africa’s apartheid government (another Helms ally). According to the Los Angeles Times, Renamo used to storm into villages, slice children in half with machine-gun fire, and hack villagers to death with bayonets and machetes.

- Roberto D’Aubuisson, the rightist politician in El Salvador most closely associated with the death-squad murders of Archbishop Óscar Romero and thousands of peasants.

- Jonas Savimbi, leader of Angola’s UNITA rebels, whose reported torture techniques included burning his enemies at the stake.

- Chile’s military dictator, Augusto Pinochet, whose tactics included throwing his political opponents from airplanes.

- Bolivian president General Luis García Meza, a reported cocaine trafficker who came to power in a coup with the help of former Nazi officer Klaus Barbie. The State Department had condemned Meza for “savage violations of human rights,” and the former president is now in prison for his crimes. Helms nonetheless courted Meza’s friendship, calling the United States’ Latin American policy “misguided.”

In Here’s Where I Stand, Helms prides himself on a foreign-policy agenda based on humanitarianism. “How could—and why should—the American people ‘write off’ the slaughter of countless thousands of innocent people as if it were no more than bad debt?” Helms writes in his book. This is a question the ex-senator must today answer himself. How could he “write off” the brutality of some of his closest allies abroad? His answer: In the hierarchy of evils, communism trumps torture.

“Have we always supported the ‘good guys’? Maybe not,” Helms concedes. “But this much is sure: It was never a mistake to give our support to the person or group who did not embrace Communism rather than the person or faction who did.” Linking communism to “the devaluation of human life,” he concludes, “In no case is the ancient rule that ‘the enemy of my enemy is my friend’ truer than when the enemy is Communism.”

ONCE HE BECAME CHAIR of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1995, Helms amassed even more power, some of it apparent, some hidden. Back then, Larry Birns, director of the Washington-based Council on Hemispheric Affairs, told me, “Whereas in the ’80s he was an obstructionist—he was of nuisance value—now he really establishes the agenda. Helms has been able to achieve what he wants to achieve, which is to be the ultimate Secretary of State. To a certain extent, there’s a diarchy in foreign policy, a rule by two: the State Department and Helms.”

The senator’s primary weapon was obfuscation. As chair, Helms could shut down the committee when he didn’t get his way—and he did, for months at a time. Important treaties like START II and the Chemical Weapons Convention languished. Ambassadorial appointments remained in limbo. The effects were devastating. In 1996, I wrote an article for The Nation chronicling some of the lesser-known consequences of Helms’ delay tactics:

In August, Guyana suffered a massive cyanide spill from a gold mine into its largest river, and no U.S. ambassador was present to marshal cleanup resources. Pakistan needed a high-level American presence when four Western tourists, including a U.S. citizen, were taken hostage in Indian-ruled Kashmir. During an unsuccessful coup attempt in São Tomé and Príncipe in August, there was no U.S. ambassador to coordinate an international response. In Thailand, issues of intellectual property, taxes, narcotics, money laundering and refugees went unresolved; so did trade issues in Gabon, Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates.

Helms, an opponent of foreign aid, also used his chairmanship to hold up vital programs, including HIV prevention efforts in Africa, democracy initiatives in the former Soviet Union, and oversight for Haiti’s elections.

In his book, Helms tells one obstruction story with some relish. When President Clinton nominated Massachusetts Republican William Weld to become the ambassador to Mexico, Helms decided the former governor’s “record was not as strong as it could be on the use of marijuana.” Helms vowed to scuttle the nomination by refusing to hold a hearing. “I was not going to insult the committee by wasting its time in discussions about a nominee who was clearly unsuited for the job,” he writes. Eventually, a bipartisan coalition used the Senate’s own rules to force the Foreign Relations Committee to convene. Helms limited the meeting to 30 minutes and moved the witness table into the hallway, relegating Weld to the back of the room without a seat. Helms used the entire half-hour to make a speech about the nomination process. Then he adjourned before allowing Democrats Joseph Biden and Paul Wellstone to have their say.

“The meeting was political theater at its finest,” he gloats in his book. And it effectively killed the Weld nomination. “More than a thousand ordinary citizens took the time to call and say they were happy with the way I handled the proceedings. Their opinions counted more with me than those of the editorial writers of the Boston Globe.”

HELMS DEVOTES AN ENTIRE CHAPTER of Here’s Where I Stand to what he calls “hot-button issues.” He equates abortion with the Holocaust; decries a school-prayer ban that he claims forbids a child from “pray[ing] for comfort for the family of a fellow student dealing with a tragedy”; and explains why conservative talk-radio hosts are more credible than The Washington Post. “The members of the liberal media have made a god of government and devalued Godly wisdom about human conduct,” he writes.

One of Helms’ hot-button issues is AIDS in Africa. In one of his few self-critical moments, he repeats his 2002 regret that he hasn’t done more to solve the international pandemic. “Perhaps, in my eighties, I may be too mindful of my soon meeting Him,” the Republican writes, “but I know that, like the Samaritan traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho, we cannot turn away when we see our fellow man in need.”

And with that, he glosses over the real hot-button AIDS issue of his Senate career: the disease’s spread in the United States.

Here’s an oft-told story that’s nonetheless worth repeating. In 1995, Patsy Clarke, whose late husband was a close friend of Helms, wrote the senator a letter about her gay son’s death from AIDS. She wanted Helms to support additional research funds; more important, she asked him “not to pass judgment” on people with the disease. The senator wrote back two weeks later. “I know that Mark’s death was devastating to you,” he said. “As for homosexuality, the Bible judges it, I do not… As for Mark, I wish he had not played Russian roulette in his sexual activity… I have sympathy for him—and for you. But there is no escaping the reality of what happened.” In the same letter, Helms also blasted “militant homosexuals” for hoisting a giant condom over his house.

Homosexuality was among Helms’ obsessions. On the Senate floor, he called gay sex a “filthy, disgusting practice” and tried to jettison political nominees solely because of their sexualities. (He did successfully stymie James Hormel’s appointment to the ambassadorship of Fiji.) He opposed federal hate-crimes legislation because it included sexual orientation. He advocated a quarantine for people with HIV. Most egregiously, he took the lead in opposing funding for AIDS research and treatment. In 1990, for example, he threatened to filibuster a $600 million bipartisan package to provide funding to cities, hospitals and agencies dealing with the health crisis. “A distinguished scientist said that there was not one AIDS case on record that did not have its origin in sodomy,” he proclaimed. “The saddest thing about all this is that an enormous amount of American taxpayer money will be used indirectly, if not directly, to proselytize a dangerous lifestyle.” Only two other senators voted to allow the filibuster to continue, but Helms’ isolation didn’t stop him from trying again. Five years later, he tried to gut another AIDS spending bill—and when the Senate overruled him 97-3, Helms announced, “There is a great odor rising from the manner in which Congress is falling all over itself to do what the homosexual lobby is almost hysterically demanding.”

In his autobiography, the former senator is curiously silent about homosexuality. But if, as he says he believes, his Maker will hold him responsible for how much he reached out to people with AIDS, Helms will probably have a bit of explaining to do in the next few years.

JESSE HELMS’ POLITICAL SHENANIGANS have spanned a wide spectrum of issues. He worked against emergency relief for farmers. He led the fight to defund controversial art. He proposed deep cuts in the National School Lunch Program. He fought against wilderness protection, particularly in his home state.

How will he be remembered in the future, though? Last summer, I taught at a camp made up largely of North Carolina teenagers. One morning, a guest speaker asked, “Who here knows who Jesse Helms is?” There were more than 100 kids in the room. Not a single hand went up. Soon, I realized, Jesse Helms will be viewed as a historical figure rather than a current-day threat. His memory will be lost to the next generation.

Sadly, we will never know what he was really like—what toxic impulses led him to embrace death-squad leaders but vilify gays, or what scared him so much about full legal equality for African Americans. “Honest confessions have always been described to me as beneficial for all humans,” Helms writes in the preface to Here’s Where I Stand. But there’s scarcely a revealing confession in the book; instead, it’s larded down with the “holier-than-thou memorabilia” that he promises to forgo. We’ll never learn why he did what he did inside the U.S. Capitol. But we do now know that he considered the building pretty to look at.

“There is no sight in the world that has ever been more stirring—for me—than the majestic white dome, brilliantly illuminated against the evening sky,” he writes. “Many are the times—especially after some tumultuous days in the Senate—when I made a point of stopping my car, occasionally getting out of it to stand with a tingle down my spine, to admire this great edifice, hoping for another day’s opportunity to uphold the Republic for which it stands.”

SIDEBAR: Helms Through the Years

“To be sure, Africa is largely uncivilized. There is support for the contention that the United Nations has moved too rapidly in creating nations… which are not ready for independence.”

—WRAL Viewpoint, 1961

“Legally, schoolboys can’t even say good-bye anymore, for good-bye is a contraction of ‘God be with you.’ Of course, if a child outside a school were calling to one inside, the outside child could still say good-bye, but the inside one would have to say ‘Stay loose’ or some other constitutional slogan.”

—WRAL Viewpoint, 1962

“By sad experience it has been learned that sexual perverts are far and away the greatest security risks possible. They are subject to blackmail at the first threat of exposure. There are untold incidents of betrayal committed by these weak, morally sick wretches who had sought and obtained government clearance.”

—WRAL Viewpoint, 1964

“A substantial part of… abusive correspondence… we receive bears the Chapel Hill postmark. Here is a community widely advertised for its climate of intellectualism, its ‘liberal’ philosophies, and its spirit of brotherhood. But if the mail we receive is fair measurement, there is room to wonder why the intellectuality of such a charming village insists on traveling a one-way street. Rarely is there an indication of tolerance for conflicting points of view, much less liberality in the consideration of them. And we have come to learn that brotherhood bearing a Chapel Hill postmark is strictly of the Cain-and-Abel variety.”

—WRAL Viewpoint, 1964

“It’s all very well and good to talk about ‘uplifting society,’ but somewhere along the line we must face the fact that from the beginning of time a lot of human beings have been born bums, but most of them—until fairly recently—were kept from behaving like bums because work was necessary for all who wished to eat. The more we remove the penalties for being a bum, the more bumism is going to blossom.”

—WRAL Viewpoint, 1965

“The Negroes of America… have a Congress which would tomorrow morning enact Webster’s Dictionary into law if someone accidentally threw it into the hopper with a civil-rights label. And the Supreme Court would stand in applause.”

—WRAL Viewpoint, 1965

“The nation has been hypnotized by the swaying and gesturing of the watusi and the frug.”

—WRAL Viewpoint, 1966

“The subject matter is so obscene, so revolting, it’s difficult for me to stand here and talk about it. I may throw up.”

—Discussing an AIDS prevention comic book, quoted in the Los Angeles Times, 1978

“I think busing is the worst tyranny ever perpetuated on America.”

—The News & Observer, 1981

“We’ve got to have some common sense about a disease transmitted by people deliberately engaged in unnatural acts.”

—Arguing for reduced AIDS funding, The New York Times, 1985

“This senator is not a goody two-shoes. I’ve lived a long time, but every Christian ethic cries out for me to do something. I call a spade a spade, a perverted human being a perverted human being.”

—Discussing homosexuality, Los Angeles Times, 1987

“I’m so old-fashioned I believe in horse-whipping.”

—The News & Observer, 1991

“She’s not your garden-variety lesbian. She’s a militant-activist-mean lesbian, working her whole career to advance the homosexual agenda.”

—Discussing HUD Assistant Secretary Roberta Achtenberg, The News & Observer, 1993

“If regular campaigns are legally sanctioned war, then my campaigns were often the equivalent of nuclear war.”

—Here’s Where I Stand, 2005

“The longer I live, the more convinced I am that God didn’t direct the creation of America in a moment of idle indifference. I believe God had a purpose for America. He had a meaning and a destiny.”

—Here’s Where I Stand, 2005

“After my amendment prohibited the NEA [National Endowment for the Arts] from using taxpayers’ money to sponsor obscenity was approved, I was showered with hoots and jeers… One memorable letter came from a woman in San Francisco who let me know she hated me and the news made her throw up. I wrote back and said, ‘Dear lady, you may be on to something. The next time that happens, put a frame around it and send it to the NEA. They will probably send you $5,000.”

—Here’s Where I Stand, 2005

“It is hardly coincidence that banishing the Lord from the public schools has resulted in schools being taken over by a totally secularist philosophy. Christianity has been driven out. In its place has been enshrined a sort of permissiveness in which the drug culture has flourished, as have pornography, crime and fornication—in short, everything but disciplined learning.”

—Here’s Where I Stand, 2005

“Watching a nice man with so little experience or familiarity with national and international issues try to project himself as an expert or refer to himself as the ‘senior Senator’ from our state simply because he arrived in the Senate chamber shortly before the immensely qualified U.S. Senator Elizabeth Dole struck me as ‘overreaching.'”

—Discussing John Edwards, Here’s Where I Stand, 2005

“On September 11, 3,000 Americans were killed by a foreign enemy. The American people responded with shock, sadness, and a deep and righteous anger—and rightly so. Yet let us not forget that every passing day in our country, more than 3,000 innocent Americans are killed at the hands of so-called doctors, who rip those little ones from their mother’s wombs. They are the most innocent victims of all—small, helpless, defenseless babies. For these unborn Americans, every day is September 11.”

—Here’s Where I Stand, 2005