Writing fiction was a bittersweet remedy for novelist Lee Smith. But it led to her triumphant return from tragedy.

Originally published in Pages.

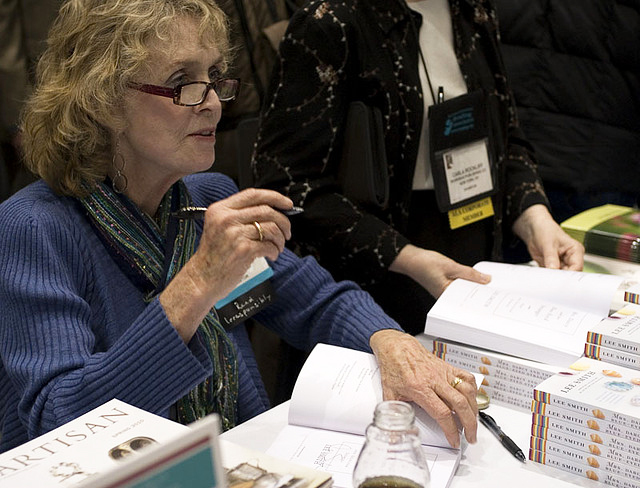

Author Lee Smith. Photo courtesy of American Libraries, the magazine of the American Library Association, reprinted under a Creative Commons license.

FOR MOST OF HER LIFE, THE CIVIL WAR held little fascination for Lee Smith. The daughter of a dime-store owner, she grew up in the Appalachian coal town of Grundy, Virginia, which had no plantations and little loyalty to either side of the conflict. Then, a decade ago, the novelist moved into a 150-year-old house in Hillsborough, North Carolina, near Chapel Hill—and found herself plunging into the era that still defines much of the South.

Shortly after her arrival, a local storyteller knocked on Smith’s door. He regaled her with a tale about one of the house’s earliest inhabitants, an aging, saturnine attorney whose unrequited lover married a Civil War hero. “If I cannot have you, my darling, I will have your daughter,” the lawyer proclaimed, then waited 16 years to marry his beloved’s firstborn. For Smith, the melodramatic story pricked a new interest in local history. Soon she found herself plowing through nineteenth-century diaries. Some mornings, before the mist lifted, she wandered through the Confederate cemetery behind her home, reading the mottled gravestones and inventing stories about the soldiers’ short lives.

“It seemed like history was catching up to me,” says Smith, sitting in the old slave kitchen she has converted into a guest cottage. “One thing that hit me was the degree that everyone, particularly in the South, was dislocated. Not only were the boys so far from home, but families were fleeing Sherman. Slaves were moving. The whole population was in transit.” Her own town, Hillsborough, grew crowded with refugees in the war’s aftermath.

Smith’s head began filling with the lives she had uncovered: a woman who had 21 miscarriages before becoming a successful midwife; a schoolmaster whose “sorest earthly trial” was her husband’s “coldness of manner”; a student whose journal triggered Smith’s own memories of attending a girls’ boarding school. These real women began morphing into the characters who would populate Smith’s newest novel, On Agate Hill (Algonquin Books). Before she could begin writing, though, Smith underwent a trauma that plummeted her into paralysis.

IN OCTOBER 2003, SMITH LET HERSELF into her son Josh Seay’s apartment and discovered the 33-year-old had died in his sleep of a heart enlargement known as myocardiopathy. For half his life, Seay had suffered from schizoaffective disorder, an illness that sometimes left the former poet and skateboarder—in his mother’s words—”almost vegetative, like a big sweet potato.” Over time, medication had controlled Seay’s symptoms, allowing him to live on his own. Every Saturday night, he played jazz and blues piano at a Japanese restaurant owned by Smith and her husband. But the medication that stabilized Seay’s brain also blew him up to 320 pounds, putting his heart at risk. Seay didn’t care. “He was so pleased with himself and his life,” Smith recalls. “He didn’t want to be crazy again.”

After Seay’s death, “I completely lost my moorings,” Smith recalls. “I couldn’t put two thoughts in a row. I couldn’t drive to Chapel Hill. I felt like I was being schizophrenic.” Like her townspeople after the Civil War, “I felt like a refugee and an orphan. I felt like my whole world had been completely overthrown, and I was trying to find my way in it.” For weeks, she ranted to a psychiatrist. One day, the doctor held up a hand. “Enough,” he declared, and handed her a prescription. “Write fiction every day,” it said.

“I have been listening to you for some time,” the therapist told Smith, “and it has occurred to me that you are an extremely lucky person, since you are a writer, because it is possible for you to enter a narrative not your own for extended periods of time.” He ordered Smith to sit at her desk for two hours every day, until the words arrived. On Day 4, they did.

On Agate Hill tells the story of Molly Petree, an “orphan girl” growing up in the wake of the Civil War in a plantation house set “upon a high prospect of sweeping vistas and incomparable charm, yet surrounded by an air of loneliness.” Through a series of discovered documents—letters, diaries, school records, a court transcript—the novel narrates Molly’s lifetime of resistance to the mantle of proper Southern ladyhood. Completing the book took three years. “At first, I was still crazy,” Smith recalls. “It would be like automatic writing. But you can’t sustain that. Your body finally wants to be healthier, and it takes over, like being hungry again. That loss becomes a part of who you are, and you go on.” Toward the end, Smith even found her son making an unexpected entrance, in the form of a character with magical gifts. “All of a sudden, he popped up,” she recalls. “He was never so happy.”

By the end of On Agate Hill, Molly Petree, now elderly, has sustained numerous losses, including the death of a child. Tragedy never defeats her. By creating Molly, Smith says, she too became undefeated. “I learned something, which is that love doesn’t end,” she says. “It doesn’t end with death, and it’s not attached to place. It lives in the mind and the heart, and those we love are forever with us.”