Can academic rigor, firm discipline, and a daily dose of religion turn boys from poor families into scholars? An intimate look at one such attempt.

Originally published in Duke Magazine.

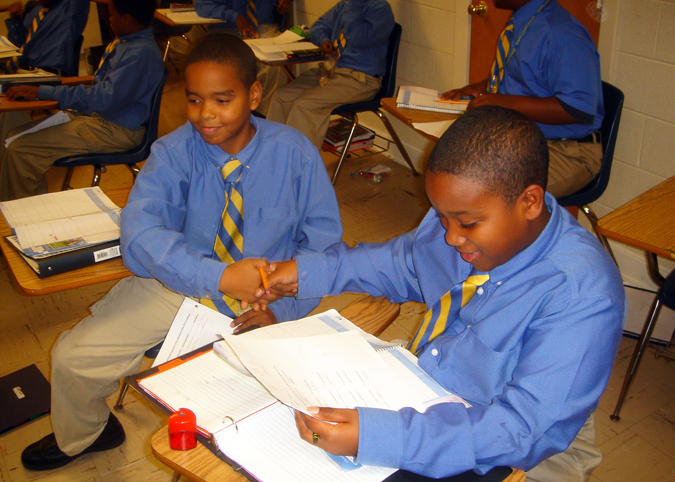

Before the fall semester Durham Nativity School, students stretch beyond their comfort zones during a retreat at Camp Kahdalea in the North Carolina mountains. Photos by Barry Yeoman.

AS AN AUGUST DRIZZLE falls outside, thirty-one middle-schoolers sit at long tables in a North Carolina mountain lodge. It’s the end of summer vacation: Next week they will begin the academic year at Durham Nativity School, an all-male, tuition-free, private middle school designed to offer a rigorous education to a handful of youngsters from poor families.

For three years, the boys will wear French blue shirts and striped ties, greet their teachers with handshakes, and enjoy a five-to-one student-to-teacher ratio. If they graduate from eighth grade, the administration will help them apply for scholarships to private high schools.

Before delving into Latin and world geography, though, the student body has retreated to the 200-acre Camp Kahdalea, where a lanky mountain guide is explaining how to safely navigate a high-ropes course. “You want to make sure your waist belt is as tight as possible,” he says, demonstrating the gear. He scans the room. “Have any questions? Comments? Fears?”

“Fears!” says twelve-year-old Kyle, punctuating his own anxiety. He has latte-brown skin and hazel eyes, a T-shirt from hip-hop star P. Miller’s fashion line, and a goofball smile that doesn’t let up, even when he’s scared.

Camp staffers hand out long ropes with lobster-claw clasps, which the boys will use to secure themselves as they walk a steel cable thirty-five feet up in the air. They point out the course’s features, including the “leap of faith,” a three-foot gap the boys must jump to complete the challenge. Kyle has never climbed so much as a ladder without his grandfather present. But during a trial run on some low ropes, his fears vanish.

“I wiggle till I giggle, and I just don’t fall down. I’m a monkey in a tree,” he announces. “When I practice, I don’t feel scared anymore. Now, any obstacle, even the leap of faith, better watch out, because here I come.”

Watching Kyle balance across a cable, it’s easy to believe he can overcome anything. A self-described “pink energizer bunny,” he belts out Elvis songs and Broadway tunes; raps freestyle with élan; and strikes 1950s Adonis poses with a keen sense of physical comedy. “He could probably sell salt water to any fish,” says the school’s founding headmaster, Troy Weaver ’83.

What he can’t do well is read and write. Diagnosed with a learning disability, Kyle struggles with spelling and cannot make sense of subjects and predicates. “He’s so used to being able to do everything well, the fact that he can’t do something well really grates on him,” says his mother, who raises three sons, works at a call center, and takes online business classes.

Up in the air, Kyle gains his footing on the cable and practically glides across the ropes course. How will this translate to the classroom, for him and thirty others? Can small classes, compassionate discipline, and a daily dose of religion guide these young men across an economic and academic leap of faith?

DURHAM NATIVITY SCHOOL (DNS) OPENED five years ago with a bold premise: Take a small number of promising boys from low-income households. Spend $19,000 per child each year, compared with $8,400 in the public schools. Dress them in uniforms; limit class sizes to fifteen; and teach them manners, study habits, and volunteerism alongside the standard middle-school curriculum. Track them through high school and college, with the expectation that they’ll eventually return to Durham as civic leaders.

It’s a concept that dates back to 1971, when the Jesuits started a school on New York’s Lower East Side focusing on social and spiritual development. Others followed suit until more than fifty faith-based middle schools came together as the NativityMiguel Network.

NativityMiguel schools feature extended academic days and years. They don’t charge tuition, but they do expect intensive parental involvement. They emphasize structure and discipline. And they get results: According to the network’s website, 90 percent of graduates go on to complete high school. Most attend college.

Boosters find these numbers compelling, particularly as other efforts to close the nation’s learning gap have failed. In 2005, three years after the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act, 12 percent of black and 15 percent of Hispanic eighth-graders qualified as “proficient” in reading, compared with 39 percent of their white peers.

It took a Duke surgery professor to bring the Nativity model to Durham. As Joseph Moylan neared retirement age, he recalled his own son’s experience tutoring a less fortunate classmate, and wondered how to reach more children who lived in poverty. Visiting schools across the country, he took notice of Nativity’s academic success rate. “Our vision was that we could create a university laboratory school,” he says. He imagined Duke professors teaching some of the classes, while public-policy researchers studied the results. (So far, this has not happened.)

Moylan recruited a Duke-heavy board, including Dean of Students Sue Wasiolek and alumnus Tom White, a former president of the Greater Durham Chamber of Commerce. He solicited funding from GlaxoSmithKline, IBM, Home Depot, Citigroup Smith Barney, and an array of churches and foundations.

Seeking a headmaster, he tapped another Duke graduate. Troy Weaver had taught at the Durham County Youth Home, a facility for juvenile offenders, as well as the prestigious Cary Academy, near Raleigh. As an African-American educator, he particularly relished the idea of reaching out to minority males — the school does not discriminate by race, but the student body reflects its location in a predominantly African-American and Hispanic neighborhood.

“I felt this would be a proactive stance to get them at a younger age to keep them away from a life of crime,” he says. Weaver also liked Nativity’s religious bent. “What burned me up is that these kids can’t pray in school, but the first thing we throw at them at the detention center is a Bible,” he says. Weaver hired a multiracial faculty to carry out his vision, and the school opened its doors in 2002.

Today, some of DNS’s greatest supporters come from the Duke community. They trek across town to East Durham, past chemical and asphalt plants, to a business district where grates protect storefront windows and Stella’s Restaurant offers up liver-pudding and fried-bologna biscuits. DNS is located on the top floor of a red-brick Baptist church: a cluster of blue and yellow classrooms reached by way of an L-shaped hallway lined with donated lockers. “When you visit, several things strike you,” says Cynthia Brodhead, the wife of Duke President Richard H. Brodhead. “First is the dignity and self-confidence of the students. Second is the high expectations that the teachers and staff have for the students, and the way the students internalize these expectations and make them their own. Third is the strong school spirit: the atmosphere of belonging, of commitment, and mutual support.”

How to create and maintain that atmosphere is a challenge DNS’s educators struggle with daily.

EVERY MORNING, FIRST THING, the entire Nativity School comes together for announcements and vocabulary review. The students offer prayer requests for sick grandmothers, traveling uncles, and crime victims they saw on TV. They link elbows with their teachers and one another and recite the school creed: As DNS men we will never give up; never be silenced by injustice, ignorance, or prejudice; never be alone, for God and our DNS brothers are with us always.

As the fall trimester begins, faculty members spend as much time teaching social skills — standing straight, making eye contact during handshakes — as they do teaching astronomy and grammar. “I’m going to be giving you life lessons,” says humanities teacher Karen Walters on Day Two. “If it seems like I’m fussing, maybe I am. That’s me, trying to get you to be the best possible you you can be.”

By the week’s end, Walters’ sixth-graders are performing songs they’ve written about the importance of studying. In front of their peers, some of the boys are natural hams. Not Reginald, a beefy eleven-year-old with a prominent jaw and earnest gaze. Reginald came to DNS an honors student, planning to work his way into Duke’s Class of 2017. At the moment, though, he looks like he’d rather be anywhere but in front of the whiteboard. He mumbles his song sotto voce, but before he can wriggle away, Walters calls him out. “Was your heart in that?” she asks.

“No,” Reginald says. He studies the floor.

“If you think something is the worst thing you’ve ever written, you’ve got to make it look like the best thing since Roots,” Walters says.

She walks to the front of the room and places a hand under Reginald’s chin. “I’m using you as an example,” she says. “I’m not picking on you. Care about what you write! I’d like for you to do it again.”

“Can I sit down?” Reginald asks. Walters doesn’t let him. “Give me some feeling,” she says. “You are articulate, handsome. You know what’s going on. Do we believe in him?” “Yes!” the other boys shout.

“These are your brothers, son,” Walters says. “We’re just waiting.”

When Reginald finishes his rap (Test taking, test taking / You gotta study / Studying is fun / It’s all about the college), his classmates whoop. “I’d pay money for that,” says Kyle, patting his friend on the back. Reginald doesn’t quite believe it, but Walters refuses to let the boy dwell in self-doubt. “We’re in a house of the Lord,” she says. “Negativity is out the door.”

SOME OF THE BOYS ARE HARDER TO REACH. They have incarcerated parents; they live with aunts and grandmothers; they harbor violent streaks. Sometimes their wild behavior sets off chain reactions, sending their peers into rule-flouting bedlam.

In Walters’ humanities class one day, the students huddle and write skits using a single type of sentence. The imperative group capitalizes on Kyle’s comic timing. Their dialogue is a succession of rapid-fire commands shouted by pint-size soldiers: “Get down! Give me twenty-five crunches!” “You give me twenty crunches!” But in the interrogative group, twelve-year-old Lawrence sits sullenly. He’s a football enthusiast with a build to match, and when he feels cocky he can put on the dance moves. But in the classroom his eyes often look glazed and bloodshot.

Walters walks over to Lawrence as the bell rings. “You have to participate,” she says quietly. “It’s not always going to go the way Lawrence wants it to go. It’s called ‘go with the flow.'” The young man packs his books silently. “Lawrence, don’t let this affect the rest of your day,” the teacher says. “To me, it’s forgotten.”

For all the talk of being a non-sectarian faith-based school, DNS has a distinctly evangelical bent.

Lawrence’s struggles with impulse control are legendary among his teachers. He pushes his way into lines. He takes forever to copy down assignments. He cuts up, then dozes off. But he also asks teachers to write messages to his aunt when he behaves well. And he takes pride in his pressed shirt and tie. “I want to be a gentleman,” he says. That presto-chango personality mystifies his teachers. “How do you go from nice to thug?” asks Walters. “He doesn’t know where his place is.”

Until he was seven, Lawrence had little guidance about his place. After his father died in a car accident, Lawrence’s mother went into a protracted decline. “She lived a really rocky life,” says his aunt. “He would have to provide meals for himself. He would go to the corner store and buy candy and honey buns.” By the time Lawrence came to live with his aunt and uncle, he was malnourished and had dental problems. He had also failed kindergarten and learned to stuff away his feelings, she says.

“He has had so many disadvantages in this short life of his — I can’t even imagine what he’s going through emotionally,” adds the aunt, a cancer survivor who also suffers from diabetes and narcolepsy. “Because I have some illness and I’m a woman, he doesn’t tell me the things that worry him. He says, ‘I’m all right, auntie, I’m okay.'” Recently Lawrence’s grandfather died, and another uncle perished in a car wreck. Invited to the funeral, “he said he couldn’t take it,” recalls his aunt. “He couldn’t take one more death.”

DNS’s admissions committee split over Lawrence. The boy didn’t help matters when he got into a fight during a summer transition program. Afterward, “I talked to Mr. Weaver,” says his aunt. “I didn’t beg him, but I told him, ‘Lawrence needs this program.'” By then, Weaver had taken a liking to the boy and believed his potential could be coaxed out by the right educators. “There’s so much about Lawrence that I could just see. I wanted him so badly,” Weaver says. “If he wasn’t with us, he’d probably fall apart.” Now, Lawrence and his aunt ride the city bus forty-five minutes to school. She drops him off at 7:45, then walks the five miles home.

THE FIFTH ANNIVERSARY OF SEPTEMBER 11 falls on a Monday, the day DNS holds its weekly chapel service. This week’s gathering features a skit written by Fred Passmore, a radio evangelist who runs a website called christianskitscripts.com. It portrays two co-workers at New York’s Twin Towers. Mike, a Christian, has just been fired, but he knows God has a plan for him. As he packs his belongings, he begs Jeff to give up womanizing and accept Christ. “Sometimes hell comes right up behind you, out of the blue, and swallows you down without warning,” he says.

Jeff doesn’t listen. As the skit ends, we learn he has engineered his friend’s dismissal for his own gain. “Word of my promotion is already spreading like wildfire through the Trade Center,” he says, clapping with glee. “September 11, 2001, is definitely going to be a day to remember!”

The moral is clear: The nonbeliever is doomed to fiery destruction and damnation. It’s a message DNS students have heard more than once.

Nathan Eubank says Latin gets kids excited about learning — “and that can help them think of themselves as young scholars.”

DNS promotes itself as rigorously nonsectarian. “We are not a religious school. We’re faith-based,” founder Moylan says at a fundraising lunch. “On a weekly basis, we have people of every religious diversity come to this school so the boys are exposed to every imaginable religion.” In reality, the school’s spiritual tone has been set by the beliefs of its staff. Weaver belongs to the United Pentecostal Church and has taken students to Sunday worship services. Many of the instructors attend evangelical churches. One notable exception is Latin and religion teacher Nathan Eubank, a self-described “Catholic-sympathizing Presbyterian” whose office door carries a sign with the words, “When Jesus said, ‘Love your neighbors,’ I think he probably meant, ‘Don’t kill them.'”

DNS’s curriculum features two years of Bible studies, followed by a year of world religion. In addition, science teacher Dan Vannelle teaches the Old Testament account of creation alongside Darwinian evolution, and holds students responsible for mastering both. “At some point, I tell them what I believe: the Biblical account,” says Vannelle, a retired dentist. “I couldn’t do that in a public school. I’m grateful.”

Parents and guardians say they share that gratitude. Without religious instruction, DNS “would serve no purpose,” says Lawrence’s aunt. “Those are the tools that you need for life. That’s what helps keep things in perspective for the young men.” Under Weaver’s tutelage, she notes, Lawrence was baptized at United Pentecostal Church.

The mother of thirteen-year-old Kenneth, also a Pentecostal, finds DNS’s approach refreshing. In the public schools, she says, “you can talk about Allah. You can talk about Buddha. But when it comes to Christianity, they talk about the Dark Ages and don’t talk about any of the positive things Christianity has done.” She’s particularly angry that public schools teach “the theology of evolution, and don’t even consider creationism as a valid point.”

For her, it’s important that Kenneth’s education echo his religious training at home. “I talk to him about consequences of actions like fornication,” she says. “Here, it’s reinforced, and to me that’s important — the relationship with God. Here, you don’t separate one from the other. It’s all together.”

Science teacher Dan Vannelle with a student. After this article was published, Vannelle was named Head of School.

BY MID-TRIMESTER, EVERYONE’S FAITH has been challenged by a series of difficult events. First, a promising sixth-grader transfers to public school without explanation. “That is a blow to us — to lose one too early,” Weaver tells the boys. “I think this is a decision he may regret. Before you make wrong decisions, I want you to be prayerful about them.” At DNS, public schools are sometimes described as gang-ridden institutions where black and Latino males can lose their way.

Then, one Monday, Weaver doesn’t show up. Over the weekend, he had flipped over a church bus with nineteen children aboard, including Lawrence. None of the kids was seriously hurt, but Weaver landed in the hospital with a broken leg and other injuries. He will not return for the rest of the trimester. Lawrence, who has lost two adults to car accidents, is deeply shaken. “It felt like some kind of dream,” he would later recall. “The bus could have caught on fire. But God put his hands on us and helped us.”

For many DNS students, disaster has been a regular part of growing up. Perhaps that’s why many of the questions in astronomy class concern the end of the world. “If the sun becomes a white dwarf, won’t all of life on Earth die?” Kyle asks one afternoon. Vannelle assures him that the end is billions of years off.

“What if it was tomorrow?” Kyle persists.

For the faculty members, there are more immediate concerns. At mid-trimester, Kyle’s literacy skills have barely budged, and Lawrence continues to misbehave. Both boys are failing multiple classes. Says Lawrence’s aunt, “He is very tearful. He’s even depressed. He knows that he has disappointed me and himself.” Along with nine others, Lawrence has landed on academic probation, with the prospect that he’ll be expelled if he doesn’t shape up in the long run. “I’m stressed,” he says. “I’m trying to figure out how I’m going to get my grades up and stop being bad.”

Still, some students are prospering. Several, including Reginald, are pulling A’s and B’s. In Eubank’s Latin class, boys who struggle with English grammar are mastering the nominative, accusative, and genitive noun cases. Twelve-year-old Travis, whose drug-using mother abandoned him to his grandmother, has a mischievous streak that often lands him in trouble. But in Eubank’s class, he pluralizes amica laudat to amicae laudant and often beats more studious boys during translation contests. “Latin is important because the structure of the language is very different from English,” says Eubank. “It requires students to understand how they make meaning.” That in turn sharpens their analytical thinking. What’s more, Eubank says, Latin’s exoticness gets kids excited about learning — “and that can help them think of themselves as young scholars.”

JOSEPH MOYLAN TAKES PRIDE in these young scholars. Once a month, the founder invites community leaders to a PowerPoint presentation in DNS’s Spanish classroom. The October guests sit on plastic chairs with built-in writing tablets, munching Quiznos subs.

“This program is taking children who are falling through the academic and social cracks in our society and allows them to achieve at a very high level,” Moylan tells them. Of the students who complete the three years, “90 percent will graduate from college.” The screen flashes with a list of private high schools DNS alumni attend: Durham Academy, Carolina Friends School, Word of God Christian Academy, Ravenscroft School, Baltimore’s Archbishop Curley High. Moylan goes on to share data from the Iowa Test of Basic Skills. It shows that five students entered DNS’s first class, the Class of 2005, with a median language score below grade level — and graduated almost two years ahead. In reading and math, they progressed from average to slightly above.

“Why does it work?” Moylan asks. “It is impressing on these young men that [success] is their responsibility.” Every morning, he says, a teacher greets them with handshakes and asks whether they’re ready to learn. “At the end of the day, somebody in charge will say, ‘Did you do your best today? And if you did, come back tomorrow.'”

Visitors come away moved, and often eager to donate or raise money. Their impulse isn’t surprising. Moylan’s presentation taps into one of the most enduring and optimistic American narratives: the story of an exceptional teacher performing miracles, even in the face of deeply entrenched poverty and discrimination. Try watching Freedom Writers — in which Hilary Swank (as the real-life Erin Gruwell) turns a class full of California gang members into published authors — without shedding a tear. Or the climactic scene from Coach Carter, where Rick Gonzales, as the heat-packing Timo, stands up and recites peace activist Marianne Williamson’s words: “Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness, that most frightens us.”

Miracle workers, if rare, do exist. Gruwell engaged her students with the war diaries of Anne Frank and Zlata Filipovic, a young refugee from Sarajevo — then passed out journals so the teens could chronicle their own violent lives. All 150 of her students went on to college. Often, though, these stories take on a mythic quality. Just as Coach Carter offered a rosy rendering of Ken Carter’s career at another California high school, Moylan’s presentations tend to be idealized. They overstate the availability of resources such as tutoring. They glide over DNS’s attrition rate: In the first two classes, ten of the twenty-one incoming sixth-graders failed to complete the three-year curriculum. And they exaggerate the success of similar schools. According to the NativityMiguel Network, the college entrance (not graduation) rate of those who complete middle school is 68 percent — 16 points above the national average for students from poor families, but considerably lower than Moylan claims. Moylan says he bases his figures on telephone conversations with a few older Nativity schools. He doesn’t have hard data.

BEHIND THE SCENES, DNS’S TEACHERS feel less optimistic than Moylan. In a series of meetings, they grapple with a dilemma educators have eternally faced: how to teach intelligent, motivated children alongside those who are still mastering basic literacy. What’s more distasteful — to leave the slowest behind or to bore the smartest? Is it fair to try to teach both in the same classroom? “I don’t know the mission of this school,” says Manuel Montaño, the math and Spanish teacher. “Is it to save the best students, or is it to save everyone?”

Moreover, the teachers despair that many students behave like gentleman only under the spotlight. When the adult visitors leave, the hallways fill with trash, noise, and the occasional scuffle. “We need to get our confidence back,” says Sally Keener, an educational consultant and DNS board member, at a meeting devoted to discipline issues. “We have to redeem our school. Do you realize we’ve lost it?”

“We never had it,” replies Eubank, the Latin teacher.

The day after the Executive Lunch, the faculty gathers to discuss one of the most beloved students. Kyle — the “pink energizer bunny” — continues to fail. During a humanities assignment, he labeled the continents Afica, Eurp, Northamarc, and Atrala, even though he was copying from a worksheet. On his science midterm, he spelled spectroscope SpicDan. Kyle demonstrates his smarts daily: He has lightning-fast wit and a vast library of memorized song lyrics. “He can tell me things,” science teacher Vannelle explains to his colleagues. “But if you ask him to write it, it’s not even in the ballpark.”

Now, months late, Kyle’s complete public-school records have arrived, revealing a learning disability deeper than anyone had surmised. “He’s been in special ed since second grade,” says school counselor David Wise. “Academically, he’s always performed notably below grade level. There was some major disparity between what his ability seemed to be and how he actually performed.”

This news represents a crisis on multiple levels. DNS isn’t equipped to teach children with severe disabilities. “Without intense support, I don’t feel like I can give him what he needs,” says Walters. Yet Kyle’s spirit is one of the school’s unifying forces. Losing him would blast a crater in the sixth grade.

After thirty agonizing minutes, everyone acknowledges that the public schools have greater resources to provide specialized instruction to children with learning disabilities. “There’s only so much we can do,” says Wise. “And if we don’t believe we can do enough, it only stands to reason to seek for withdrawal.”

Eubank grasps at one final straw. “Hypothetically, what if we did something, and it wasn’t a strain, and he started doing better?”

“If a miracle happens, I wouldn’t be averse to keeping him,” Wise says. But he reminds everyone that in the recent Iowa Test, Kyle got less than a third of the correct answers in spelling, punctuation, and math computation.

Eubank grimaces. “My list of students I’d rather lose is about thirty names long,” he says. Others chuckle awkwardly. “I’m serious,” he says.

DURING THE LAST CHAPEL of the trimester, the guest preacher is Vensen Ambeau, DNS’s after-school coordinator. The boys know Ambeau as the studious-looking man with dreadlocks who oversees recess. But he’s also an ordained African Methodist Episcopal minister. Today he has prepared a message in hip-hop style: “It’s not the bling on the ring, or the shine on the chain, or the squeaks on the sneaks. It’s how we see our life in Christ.” As the sermon progresses, Ambeau’s message gets closer to the harshness of the boys’ lives: “At home you get cursed at for looking at someone and probably told your daddy wasn’t anything so you won’t be anything. That’s a lot for you to have to deal with at this age; and I don’t want to say to you the best way to deal with your issues is to simply get over it. I want you to know God is traveling with you to heal the emotional and spiritual hurt that life has brought upon you.”

The kids are riveted. As he ends the sermon, Ambeau comes back to Marianne Williamson’s words, the ones from the pivotal scene in Coach Carter:

We ask ourselves, Who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be? You are a child of God. Your playing small does not serve the world. There is nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won’t feel insecure around you. We are all meant to shine, as children do.

When Ambeau finishes, the boys flock around him. He has given voice to their aspirations. But as the trimester ends, their realities are decidedly more complicated than Williamson’s lofty words.

Twelve of the fourteen boys from the sixth-grade class remain. Lawrence is warned that he needs to pull up his grades if he wants to stay at DNS. Kyle has surprised everyone by scoring a B on a science quiz, but the learning problems persist. By Christmas, he is gone.

Reginald has aced most of his classes. He has come to think of the school community as an extended family. “I have a whole bunch of moms and a whole bunch of dads,” he says. He views his classmates’ success as his personal responsibility, and has taken to tutoring Lawrence. Reginald’s father notices a change. The boy doesn’t try to slide on his reputation, as he once did. “He’s always been a pleasant, well-mannered kid,” the father says. In the past, teachers would forgive Reginald for missing assignments “because he’s such a nice kid. Now he’s more than a nice kid. He’s a man.”

Travis, the Latin whiz, has finished the trimester with all passing grades. He still gets into trouble, but his grandmother says he has “settled down a bit. He’s paying more attention to things.” When Travis’ brother entered DNS’s inaugural class, “he was a mean little rascal,” the grandmother says. But the school “turned him around,” and now he attends the rigorous Asheville School in western North Carolina. Travis says he wants to emulate his brother, “so I can maybe help my grandma when she gets old.”

The challenges of educating these students often overwhelm DNS’s faculty. “My soul is tired,” Walters tells the boys toward the end of the trimester. Two of her colleagues, Ambeau and Montaño, will resign their positions in the coming weeks. Likewise, Weaver, the headmaster, will not return after his extended medical leave. But Walters will be back, ready for another stretch. “I always tell them that I’m in the middle waiting for them,” she says. “If they meet me halfway, I’ll do what I can to carry them the rest of the way.”

Note: As we produced this story, we struggled with how to protect students’ privacy while honestly depicting the challenges facing poor students, their parents, and their teachers. To achieve this balance, we have changed the names of the children in the story.