Like his city and his newspaper, a survivor.

Originally published in Columbia Journalism Review.

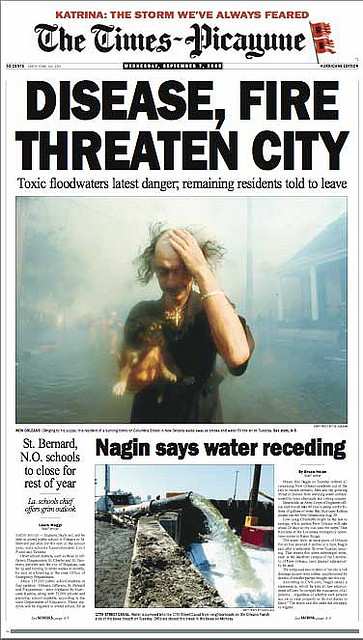

ON A BREEZY SUNDAY MORNING in October 2006, residents of New Orleans—displaced, exhausted, wondering if they would live to see their city’s resurrection—woke to one of the most audacious acts of mass psychotherapy ever performed by an American newspaper. It took place under an unlikely byline. Chris Rose, a columnist for the daily Times-Picayune, was once known primarily for reporting on the bad behavior of visiting celebrities.

Hurricane Katrina changed that: It transformed Rose into a plaintive voice for a struggling city. His columns detailed the emotional toll of living amid still-flatted houses and daily reminders of the 1,500 who died in the storm’s aftermath. And then, more than a year after the breached levees plunged whole districts underwater, Rose was sharing with readers the story of his own descent. Rose’s column was promoted on page one and dominated the paper’s Living section:

I should make a confession. For all of my adult life, when I gave it thought—which wasn’t very often—I regarded the concepts of depression and anxiety as pretty much a load of hooey. I thought anti-depressants were for desperate housewives and fragile poets. I no longer feel that way. Not since I fell down the rabbit hole myself and enough hands reached down to pull me out. One of those hands belonged to a psychiatrist holding a prescription for anti-depressants. I took it. And it changed my life. Maybe saved my life.

For the next 4,000 words, Rose described a spiral familiar to many Katrina survivors: the “crying jags and fetal positionings,” the “thousand-yard stare,” the inability to hold conversations. “I’d noodle around on the piano, read weightless fiction, and reach for my kids, always, trying to hold them, touch them, kiss them. Tell them I was still here,” he wrote. “But I was disappearing fast.” Finally, Rose described how the anti-depressant drug Cymbalta helped clear away some of that darkness, enabling him to function again.

In few cities would such a personal account have received such prominent play—or elicited more than 6,000 e-mails. But Katrina has transformed how journalism is practiced at The Times-Picayune. It has blurred the lines between those who suffer and those who chronicle that suffering, and has challenged traditional notions of objectivity. And it has become a better newspaper in the process. Every reporter and editor was directly affected by Katrina, and the Picayune’s pages are suffused every day with outrage and betrayal—and with solid reporting. The paper has relentlessly investigated the Army Corps of Engineers, which built New Orleans’ faulty levees, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, whose response to the storm provoked such frustration and anger. It has sounded the alarm about Louisiana’s disappearing wetlands, which would render New Orleans even more vulnerable during the next hurricane. And it has sent reporters to Japan and the Netherlands to learn what makes successful flood-control systems work.

And the newspaper has bonded with its readers; the Picayune is an essential part of coffee-shop conversation all over the metropolitan area. At a time when dailies are wondering how to hold onto wandering readers, it has proven that a paper that claims a stake in its city’s survival, reporting with passion and voice, can remain an essential part of the civic conversation. “Other papers would kill to be that relevant,” says Harry Shearer, the actor and satirist and part-time New Orleanian.

No Picayune writer epitomizes this transformation more than the forty-seven-year-old Rose, whose journey through breakdown and redemption spurred a communal catharsis. “He bled for us in those columns,” says Linda Ellerbee, the former NBC anchor who covered Katrina’s aftermath for Nick News, a children’s broadcast. “He made it more real than any photo, any TV coverage could—more than Anderson Cooper crying on the air, more than Sean Penn going though the water in his boat. He let us into his dark places. In the old-fashioned, Biblical sense, he bore witness.”

BEARING WITNESS HADN’T BEEN IN ROSE’S PLANS. After covering crime, presidential politics, and regional features at the Picayune for fourteen years, he was tapped in 1998 to replace a retiring gossip columnist. He set out, he says, to “dirty that column up” and engage younger readers. “I was over reading about where rich white folks went on their vacations: ‘Bill and Buffy Moriarty recently back from Aspen, where they report that little Molly is doing very well in film school.’ I’m going, ‘Whoa! Guys! We’re almost at the end of the century here. They should send that out in their Christmas newsletter. That doesn’t belong in the newspaper.'”

Rose reading from “One Dead In Attic” at the Maple Street Book Shop in 2007. Photo by Infrogmation, published under a Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Reinventing the column, Rose took readers to an oxygen bar in the suburbs and a male-stripper revue downtown. He took aim at stars making the New Orleans scene, including Lindsay Lohan (“America’s most famous underage drinker”) and Sean Penn (“Note to Sean, at the request of local service industry employees: ‘Last call’ means LEAVE.”) He made a sport of sassing Britney Spears, who grew up in Louisiana’s Tangipahoa Parish. After the pop singer’s fifty-five-hour Las Vegas marriage, Rose predicted she would “someday be remembered as the woman who put the ‘ho’ in Tangipahoa.” He loved pulling stunts, then writing about them. In “Straight Eye for the Queer Guy,” he assembled a group of Bud-swilling friends to give a reverse makeover to a gay bartender. He mocked the French Quarter’s tarot readers by donning a chicken-foot necklace and telling two-dollar fortunes with a Magic 8 Ball.

It was hardly immortal journalism. Still, the column was well written and filled with affection for Rose’s adopted hometown (he is a native of Maryland). “What can I say? It’s superficial stuff,” he says. “It’s pretty meaningless but I enjoyed it.” A devotee of (and former stringer for) People and Us Weekly, “I was a guy who could make a living off his hobby.”

For Rose’s last column of August 2005, he recounted how New Orleans’ growing film industry was luring his neighbors to audition as extras. Then, with Katrina bearing down, he and his family fled, taking a circuitous route that landed his wife and children in Maryland. Rose himself returned to New Orleans. His house was undamaged, but the city was in ruins, emptied of its inhabitants. With most of the newspaper’s staff in Baton Rouge, Rose and a handful of colleagues huddled in a makeshift newsroom with a windup radio, a generator, a shotgun, and two .357 revolvers. There, they produced fierce prose that won the newspaper’s staff two Pulitzer Prizes.

Rose’s writing was as urgent as anyone’s. “I saw a dead guy on the front porch of a shotgun double on a working-class street and the only sound was wind chimes,” he wrote in his September 7 column, the first after his return. From then on, three times a week, he brought readers into a world where intimacy and darkness often commingled. He wrote about the friends and strangers who gathered on his stoop every night, including a couple who returned home only to make a drunken suicide pact a few weeks later—they couldn’t stand living in “the smoking ruins of Pompeii.” The man killed himself; the woman didn’t. Rose wondered aloud, “Where are we now in our descent through Dante’s nine circles of hell?”

MEANWHILE, ROSE PLAYED DOWN HIS OWN HELL, though he also sometimes lived it in public. When he blacked out one afternoon, falling face down into the grass and not moving for hours, he wrote about it, noting that even before Katrina, “a man passed out on the side of the road in New Orleans was not a uniquely alarming sight.” For the columnist’s family, though, those first months after the hurricane were profoundly alarming. Rose, who had quit drinking a year and a half before the storm, had resumed. “There was a lot of booze and a lot of drugs around, and we were all just narcotizing ourselves,” he recalls. His wife and parents urged him to get help. He didn’t listen. Things got worse.

Photo by earthhopper, published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

After his neighbor’s suicide, “it got really cold and that kind of snapped it right there,” Rose recalls. “Nobody wanted to sit outside. And I withdrew inside.” For a five-week period he didn’t go to Maryland to see his wife and children, “and I didn’t talk to my family hardly at all. I hardly talked to anyone. I remember a friend during that period saying, ‘Dude, they call you the voice of the city, but you never leave your house. Does anybody know that?'”

By November he knew something was seriously wrong. “I was pacing,” he says. “I had the shakes. I did an interview with the L.A. Times and I had to call the guy back and I didn’t even remember what I had said to him. Not because I was drunk but because I was manic. Even when it warmed up again, I didn’t turn on the light and open the door. Sometimes I could hear people knock. I wouldn’t answer. I was scared and I was rapidly becoming very, very depressed.” Adding to his troubles was the fact that thousands of Picayune readers were sending Rose their own tales of anguish. “When he became the sounding board for everyone else’s pain, that’s when it became too much to ask of him,” says James O’Byrne, features editor for the Picayune.

Rose was not the only Picayune reporter suffering. Whenever his colleagues left New Orleans and visited the paper’s temporary headquarters in Baton Rouge, “they would be haunted,” O’Byrne says. “They would look like people who had been at war. You had to tend to them. You had to get them food and hug them and get them a shower. It was a real trauma-decompression moment for them.” Yet the staff was producing phenomenal work. In the months following Katrina, Picayune reporters debunked many of the rumors of Superdome violence; wrote lyric accounts of human suffering; and did the investigative legwork that pinned New Orleans’s flooding on engineering failures rather than nature. Rose provided the emotional barometer. “His columns were ruthlessly observed, yet filled with a dark but real compassion,” says actor Shearer. “He would start out outraging or amusing you, but by the end, you would start to puddle up, because he hit an emotional nerve.”

As Rose’s writing grew more transparent, “I was getting a daily regimen of e-mails from people who were reading my stories and asking me, ‘Are you OK?'” the columnist says. “Strangers would stop me on the street and say, ‘I know your family’s gone. Would you like a warm meal?’ One thing I was not aware of was that I was cracking up in public—that I was writing a real-time diary of a descent into madness.”

Initially, newsroom leaders didn’t know how to respond. Picayune editor Jim Amoss, a New Orleans native who’s generally credited with ramping up the paper’s quality over the past seventeen years, knew about the e-mails from concerned readers. “As an editor, you’re struggling with that worry,” he says, “and at the same time knowing that his anguish is the source of his best work.”

In 2006, Rose’s writing took a turn. “His work got really angry for a while,” says O’Byrne, who edits Rose’s column. “As he stopped writing about his travels around the city, and started writing more about how pissed off he was, I began to get concerned about him. I really urged him to see a doctor about his depression.”

ROSE’S BREAKTHROUGH COLUMN in the fall of that year, describing his depression and the lucidity that anti-depressants brought, was titled “Hell and Back,” and it ended with an altar call. For those who recognized themselves in him, Rose wrote, “Let me offer some unsolicited advice, something that you’ve already been told a thousand times by people who love you, something you really ought to consider listening to this time: Get help.”

And they did. Rose’s column “sent hundreds and hundreds of people to their physicians,” says O’Byrne. “I know that just based on the physicians that I have, who themselves got fifteen or twenty patients to come to them and say, ‘I read Chris Rose’s column. I think this may be me.'”

The next week, Rose urged readers to look for the “red flags” of mental illness in their neighbors. “I don’t mean to get all Oprah on you here,” he wrote, “but if you see the opportunity, help a guy get his shoes on, because sometimes it’s harder than you know.” In fact, for Rose, recovery was proving harder than just taking a pill. Feeling impatient, he started upping his dose of Cymbalta. Then he added painkillers to the mix. He began withdrawing again, and losing weight, until he weighed what he did in eighth grade. His columns became “unrunnable,” says O’Byrne, who spiked three in a short span of time. “They were just angry, rageful rants against life and the universe.”

Finally, last April, Rose’s wife Kelly arranged for an intervention. She and O’Byrne, along with three neighbors, confronted the columnist at his house and urged him to enter rehab. He didn’t need much persuasion. Not only did Rose understand he was in trouble, but he had an additional incentive: He had also recently learned that he was a bone-marrow match for his sister, who had leukemia. “I thought, ‘I’m gonna save Ellen’s life and then write a story that will blow people away,'” Rose says. “And I get to be the hero.” Rose went into rehab for thirty days, kicking both the painkillers and the antidepressants. But not in time to donate marrow to his sister, who died three months later.

THERE IS NO THOUSAND-YARD STARE on Rose’s face now. He is as transparent in person as his columns are. One afternoon last October, he brought forty copies of 1 Dead in Attic, the best-selling compilation of his post-Katrina columns, to a meeting of the Ladies Leukemia League in suburban Kenner. After a spirited talk—Rose repeatedly mocked the country-club neighborhood where they were meeting—his friend Jacquee Carvin raised her hand. “Is there anything else that you can personally impart to the leukemia society?” she asked. Rose let out a sigh. “You put me on the spot there,” he said.

“Just watch me and you’ll get through it,” Carvin replied.

Rose’s eyes welled up. “My sister died of leukemia in August,” he said, his voice choking. “I was her bone-marrow match, but we never made it.” He told the women about his struggle with depression and slide into drug addiction. “I was killing myself real fast. When I found out I was a bone-marrow donor, I said, ‘I’ve got to fix myself.’ And I went to rehab. So what happened was, instead of saving my sister’s life, she saved mine.”

These days, Rose laughs hard and cries easily. His marriage has dissolved, but he is hanging on. “I’m a work-in-progress,” he says, sitting on his new front porch near Tulane University and watching his children race in and out of the house. “I got these little guys; I gotta take care of them.” And Rose is trying to figure out the next step for his journalism. He’s writing fewer internal monologues and more reported stories. He feels settled into New Orleans for the long haul.

Part of the reason is The Times-Picayune itself. Since Katrina, the newspaper has found its purpose: as a super-charged advocate for the city’s survival. It doesn’t debate whether New Orleans should be rebuilt; it blasts any public official or government agency standing in the way. By writing as outraged fellow-sufferers, Rose thinks the Picayune is creating a new journalistic model, one that other dailies would be wise to follow. “It’d be interesting if every newspaper treated its community as if it were at risk,” he says. “And if you took a good look at most major dailies, they are. Not at risk of dying and being wiped off the map. But look at the state of the American city and it’s in trouble.

“I got into newspaper work because I thought it was a vital and romantic part of the American fabric,” Rose continues. “I watched those old movies with Gary Cooper about what a newspaper meant. And in truth, for most of my career, that’s not been the way it really played out.

“I got India ink in my blood,” he says, meaning he always felt compelled to write, even when there was no higher purpose. But now there is. “For the last two years, it’s like—Wow! This is what I always thought it’s supposed to be like,” Rose says. “You wake up in the morning and you kick some ass.”