A bold travel challenge is Helen Ebersole’s dying gift to her granddaughter.

Originally published in University of Northern Iowa Today.

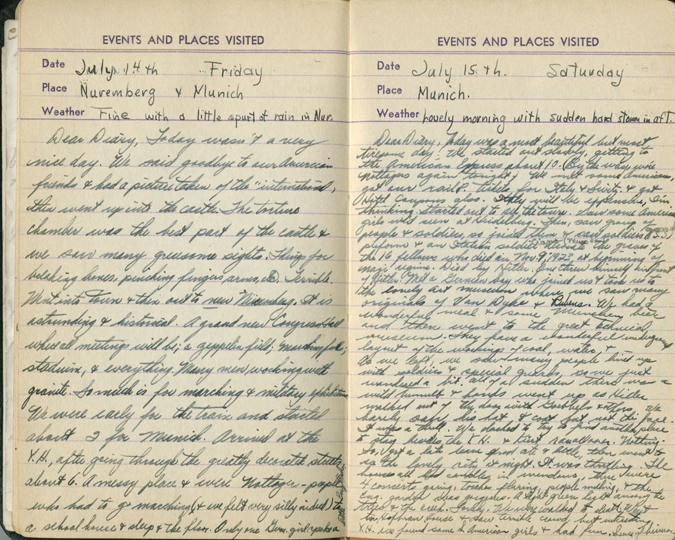

A journal entry from the day Helen Ebersole saw Adolf Hitler in 1939. Photo courtesy of Lindsey Alena Schill.

IN NOVEMBER 2004, HELEN EBERSOLE issued a challenge to her granddaughter, Lindsey Alena Schill. Ebersole, who was then 87, belonged to the Travelers’ Century Club, an organization whose members have visited 100 or more countries during their lifetimes. Ebersole had bicycled through Western Europe at the brink of World War II; circled the world with her husband, Walt, for their 30th anniversary; parachuted into Death Valley at the age of 63; and, at 80, swam in the waters off Antarctica. As a child, Schill was fascinated by the glass bowl of matchbooks from the hotels where Ebersole had slept: the Clarks Shiraz in Agra, India; the Schweizerhof in Berlin; the Bagangenna in Bamako, Mali.

Earlier in 2004, Ebersole had fallen and reinjured her hip, and Schill spent part of that summer helping out at her grandparents’ house in La Verne, Calif. During that time, “I really got to talk with her about the importance of the trips,” Schill said. “She always said it was a matter of druthers: whether you ‘druther do this’ or ‘druther do that.’ They preferred to spend their money on experience.”

That November morning during a family gathering, Ebersole stood with Schill in front of a world map covered with thread and push-pins to mark the countries she had visited. “One hundred and seven is pretty good,” Ebersole told her granddaughter. “But I’ll bet you can make it to at least 108.”

Ebersole died at home two days later. As Schill grieved, she found comfort by thinking about how to carry out her grandmother’s 108-country challenge.

Ebersole was no ordinary globe-trotter. “It wasn’t a materialistic, touristy type of travel,” said Schill, a voiceover actor. “Every trip, she made sure that she met the people and experienced the culture.”

Ebersole also kept meticulous journals, starting with the 1939 trip, when she and a friend spotted Adolf Hitler on a Munich street. “He was coming out of the museum, and the people were lined up,” she wrote. “They thought that man was a god. He had a way of making them cry.” Germany was getting ready to invade Poland, and Ebersole had already stumbled upon several Nazi rallies. “Somebody would say, ‘Heil Hitler,'” she later told Schill in an oral history. “We would say ‘Heil Roosevelt’ under our breath.” Other journal entries, spread over decades, chronicled a kava-juice ceremony in Fiji; a lunar eclipse in Niger; and French locals who couldn’t pronounce her name and instead called her “Ellen with an H.”

In the two-and-a-half years after Ebersole died, Schill wrapped up a personal goal of visiting all 50 states. Then she launched her response to Ebersole’s challenge. In 2007, Schill flew to Europe and spent two-and-a-half months in 11 countries from The Netherlands to Greece, bringing her lifetime total to 16. She visited some of the same places Ebersole had gone as a young woman, taking photos from similar vantage points as her grandmother’s pictures and marveling at seven decades’ worth of changes. “Every country I visited was sprinkled with reminders of the war that didn’t exist while she was there,” she said.

A SELF-DESCRIBED “CONTROL FREAK,” Schill nonetheless made no hotel reservations and ended up spending most nights in the homes of locals. This was her effort to learn from Ebersole’s spontaneity. “She would smile and chat with somebody,” Schill said, “and before she knew it, they were feeding her and bringing her in and showing her the town.” When Schill got into jams, “I just remembered what she said: Enjoy people and open your heart and genuinely take an interest in their culture, and they will take care of you.”

One of those moments—“when my grandmother was standing on my shoulder,” Schill says—came when she was planning her transfer from Greece to Italy. Nothing was panning out correctly. Aboard a Greek train, Schill met Dionysios, a slender 78-year-old with leathery skin and a deep belly laugh. Through charades and simple words, Schill explained her predicament. “You have time,” Dionysios said in broken English. “You stay. I show you town,” Schill thought for less than an hour, then decided, “I have time.” So she got off the train with him in Diakofto, a village on the Gulf of Corinth. Dionysios, a bachelor, gave Schill his house and stayed by himself in the guest quarters. That gave Schill five days to line up contacts in Italy.

Diakofto turned out to be a highlight of the trip. “Here you call me Greek Grandpa,” Dionysios instructed Schill. “Otherwise town go crazy.” Each day they took a different adventure in his beat-up Toyota: to a mountaintop monastery; to a hillside crevice where they came upon goats and waterfalls; to a ferry across the gulf, en route to Delphi, where the captain lent Schill his cap and allowed her to steer. “Dionysios shares stories with me about the war when he was 13 years old, hiding under the lemon trees in the mountains, dodging bombs, and burying friends,” Schill emailed her friends that week. “Life has a whole new perspective after hearing all of this.”

Since her return to Los Angeles, Schill says, she tries to remember Dionysios and others who took her under wing. “Going into different cultures by myself, I had to approach every single person with a blank slate,” she says. “I really make an effort to focus on doing that still.” Meanwhile, she’s starting to dream about her next journey: at least two months (still unscheduled) in Australia and New Zealand. She figures she has decades to reach 108 countries—“my grandmother always said, ‘The good Lord willing.'”