For 5,000 years, Spain’s mineral riches created cash economies and global pollution.

A shorter version was published in Archaeology.

AQUILINO DELGADO DOMÍNGUEZ UNLOCKS the ornamental metal door and waves me inside the warehouse of the Riotinto Mining Museum in southwestern Spain. He makes a beeline to a cardboard box sitting on a waist-high table. Inside is a gray plastic bag containing pieces of a Roman water wheel used during the first or second century A.D. to pump water out of the nearby mines. For 5,000 years, the metals dug from these mines have provided the wealth that sustained civilizations.

Miners discovered the wooden wheel during World War I. Now, Delgado is preparing to analyze the fragments using radiocarbon and tree-ring dating. The archaeologist opens the bag, thrusts his nose inside, and breathes deeply. “Smell this,” he says. The sulfur odor is not what I expected: a mixture of chocolate and licorice, sweet but not cloying. “That’s the smell I remember from my childhood,” he says.

In 1983, Delgado’s maternal grandfather—a supervisor in Cerro Colorado, the second-largest mine in the Riotinto complex—invited his four oldest grandchildren to see firsthand how five generations of relatives had earned a living. Delgado, who was nine, was the only one to accept the offer. For the next two years, during school breaks, Delgado’s grandfather dressed him in boots, a helmet, and an adult miner’s uniform—he was a tall boy—and took him through the copper, gold, and silver mines. “What my grandfather did with me was very common,” he says. “It was a way to dignify their labor.”

Delgado figures that if he were born even five years earlier, he might have ended up working in the mines himself. Instead, he left home to study archaeology at the University of Huelva, 45 miles to the south. Now, at age 36, he directs the museum dedicated to the mines where both his grandfathers once worked.

Riotinto is part of the Iberian Pyrite Belt, a mineral deposit that stretches from Spain into Portugal. It is one of the largest known mining complexes in the ancient world. Starting as a surface operation focused on copper minerals, it eventually became an industrial-scale enterprise until it finally closed in 2001 amid falling copper prices. “The name Riotinto has something of a magical connotation,” wrote University of Sevilla archaeologists Antonio Blanco Freijeiro and José María Luzón Nogué in 1969. “It has been called the geologist’s paradise because at almost no other place on the earth has nature exposed in one spot such richness and variety of minerals.”

Now that the industry is gone (for the time being, at least), Delgado and other researchers are studying Riotinto and some neighboring sites to answer fundamental questions about how metals were extracted and processed in the ancient world. But they’re also examining the nature of work, the rise of globalization, and the legacy of environmental contamination.

THE BUS FROM HUELVA TO THE VILLAGE of Minas de Riotinto is driven by Delgado’s father, one of the few men in his family who didn’t work in the mines. It takes us through workaday pueblos of whitewashed and tiled buildings with wrought-iron balconies and terracotta roofs. Waiting passengers huddle against walls, trying to protect themselves from a cold rain that has persisted for weeks. As we near Riotinto, the road starts climbing abruptly, and caution signs warn that this is a zone of frequent accidents.

On the far side of town, the highway passes modern open-cast pits, their sides stepped in 40-foot levels like amphitheaters built for giants. Visiting in the late 1980s, archaeologist Lynn Willies of England’s Peak District Mining Museum described it as a landscape turned upside-down: “The hills have literally been turned into valleys, and the valleys made into hills.” Even more striking than the topography is the landscape’s color palette: crimsons, blue-grays, and ochres, which give the place an otherworldly feel. Naturally dissolving iron, a process believed to predate the mines, has dyed the acidic river “tinto,” or wine-colored. So otherworldly is Riotinto that NASA has used robots to drill its soil—practice for the search for underground life on Mars.

Local folklore places King Solomon’s mines at Riotinto, though a more factual history has been more difficult to write. “Its birth is shrouded in the mists of antiquity,” wrote William Giles Nash, a Rio Tinto Company employee, in 1904. Archaeologists now know that the area’s Copper Age inhabitants were extracting malachite and azurite, two copper-rich minerals, during the third millennium B.C. Inside Riotinto’s museum is a 5,000-year-old stone hammer found in one of the mines during the 1980s. These hammers were used to cut trenches in the slate outcroppings—the earliest form of mining at the site.

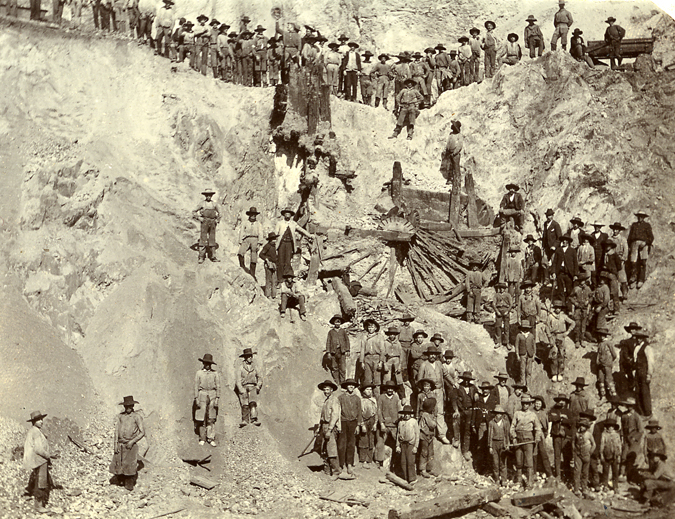

A 1990 excavation at Riotinto. Photo by Juan Aurelio Pérez Macías, courtesy of Aquilino Delgado.

The Phoenicians arrived in Spain around 1100 B.C.—their ships filled with ceramics, jewelry, and textiles for trading—and moved inland during the 9th century B.C. “They didn’t bring weapons,” says Thomas Schattner, a professor of classical archaeology at Germany’s University of Giessen. “They walked in, they exchanged goods with the indigenous people, and they were received.” There is no archeological evidence of hostile attacks, Schattner says, which lends credence to the written accounts of peaceful trading.

At Riotinto, the Phoenicians found the silver and copper mines run by an indigenous people called the Tartessians. Even after the foreigners’ arrival, the mining operations remained in local hands—though the amount of Phoenician influence remains a point of contention. “None,” says Delgado, dismissing those who believe, in his words, that “without the arrival of foreigners, the indigenous people would still be like Adam and Eve.” He argues that that only a few Phoenicians lived in the area, where they served as commercial agents. Schattner calls that answer “one-dimensional,” noting that both written evidence and the size of the slag heaps show that silver production spiked at mines like Riotinto after the Phoenicians’ arrival. Delgado contends this is solely because of higher demand; Schattner disagrees. Among the finds at Riotinto, Schattner says, are rectangular clay nozzles that had been attached to leather bellows, which pumped air into smelting furnaces. “The introduction of bellows is one of the most important contributions of Phoenician technology,” he says. “It permits bigger ovens, higher temperatures, more successful melting, and much bigger amounts of metal. It’s the beginning of industrial production. You would not obtain this amount of silver by using the old-fashioned technology.”

Beyond mining, the Phoenician arrival sparked “a kind of globalization,” says Schattner. In the seventh century B.C., the eastern Mediterranean was shifting toward a coin-based economy, and the Phoenicians needed silver to decorate their temples and pay their debts to the Assyrian empire. Silver—which was shipped off the Iberian Peninsula in bars or ingots, according to shipwreck evidence—was the perfect currency, he says: rare enough for coins to have value but common enough for many people to participate in the economy. “Without the silver mines of southern Spain, the development of money would have been quite different—based on a medium that was less ideal,” Schattner says.

The globalization was cultural, too, Schattner argues. He has been excavating at Castro Cerquillo, a Phoenician-era village outside the Tharsis mines, 40 miles west of Riotinto. There, he says, “we made the astonishing observation that the new settlements of the indigenous people are being built in an Eastern manner, with orthogonal streets like New York, at right angles, making blocks—a very modern manner for that time.” While the Phoenicians were extractors of wealth, Schattner says, they were also “distributors of ideas—for cities, for material culture, for houses, for living.”

THE ROMANS TOOK OVER RIOTINTO in 206 B.C. after defeating and expelling the Carthaginians, who had occupied the region since about 535 B.C. With the technical knowledge of Rome’s military engineers and the availability of slave and convict labor, the Roman operations at Riotinto grew colossally, peaking from A.D. 70 to 180. Their magnitude far exceeded anything that came before. During that period, Delgado says, Riotinto was the largest silver and copper mining operation in the Roman Empire.

“The excavations in the mines themselves, the investigations of the slag heaps, and the cemeteries and mining settlements show that the sheer scale is much more important in the Roman period,” says Jonathan Edmondson, chair of the history department at York University in Toronto. “With thousands of laborers and Roman soldiers and administrators camped out, they would have been hives of activity.”

The Romans mined Riotinto by digging shafts of up to 450 feet deep, which required elaborate ventilation and drainage systems, including wooden water wheels and a system of gently sloping drainage channels that remained in use well into the 20th century. They also developed a sophisticated system of governance. Two bronze tablets unearthed at Aljustrel, another Pyrite Belt mine across the Portuguese border, spelled out the rules by which the Roman government would lease Iberia’s mines to individual conductores, who paid 50 percent commission on the ore they excavated. The tablets, discovered in 1876 and 1906, also covered mine safety, the treatment of slaves, and the granting of concessions to barbers, auctioneers, and cobblers. Bathhouse owners, who bought franchises, had to keep the water heated year-round, polish the metalwork every month, and admit women and men at specific hours.

The scale of mining at Riotinto fundamentally altered the Roman economy. “Basically, it ensured Rome a constant supply of fresh metal for increased minting of silver and lower-denomination copper-based coins,” says Edmondson. Rome used silver denarii to pay and feed its army, fund public building programs in its capital city, and subsidize the price of (and eventually allow free distribution of) grain to the city’s residents. But following the invasion of Spain by the North African Mauri in the late second century, mining activity dropped off and the denarius plummeted from 97 percent silver to 40 percent, leading to outsized inflation as Roman minted ever-less-valuable coinage. “The Roman state experienced major problems, since taxes were paid in coin,” Edmondson notes. “People started handing over these debased coins in payment of taxes, while hoarding the [older] higher-percentage silver coins.” By the fourth century, he says, gold replaced silver as Rome’s main currency.

After the Roman era, the Visigoths allowed Riotinto to go dormant, though the mines did experience a small-scale resurrection during the Islamic Period (particularly the 10th through 13th centuries). They weren’t rediscovered until 1556, when a priest named Diego Delgado set out to search for new mines at the behest of Spain’s King Phillip II. “In these parts I have discovered very important secrets,” wrote Delgado in a letter to the king, in which he enclosed three buttons of silver. But little came of the mines until 1873, when the British-based Rio Tinto Company developed them into a gigantic operation with open-cast pits and its own railway. The company built a Victorian village called Bella Vista (cricket field and all), along with its own hospital and school system. At the peak, in 1910, 17,822 people worked for the mining company, in a landscape altered beyond recognition.

That was the culture into which Aquilino Delgado Domínguez was born.

DELGADO’S RELATIVES’ WORK WAS NOT SO DIFFERENT from that of their forebears. “For 2,000 years it was done by hand, by pick and shovel,” he says. His paternal grandfather, who died when Delgado was six, worked one-third of a mile underground, naked except for helmet and boots because of the 120-degree heat. The work was not only brutal; it was also unhealthy: The archaeologist vividly remembers the coughs of neighbors who had contracted the incurable lung disease silicosis, which often afflicts miners who inhale silica dust.

Debilitating as it was, mining kept the economy humming in this remote corner of Spain. When Riotinto’s owners introduced labor-saving technologies in the 1960s and ’70s—including automatic loaders that could be guided into the most dangerous areas by remote control—miners sabotaged the equipment out of fear for their jobs. “They would put pyrite powder in the injectors to break them down,” Delgado says. “They would do the same with the automatic drills.”

Starting at age four, Delgado went with his maternal grandfather to an all-male social club where miners drank coffee and aguardiente (a strong liquor made from anise), watched soccer, and played cards. He loved listening as the older men chatted. “You cannot find these stories in any history book,” he says. “For example, my grandfather’s work documents talk about when he was given a break for the birth of my mother, or when he was given a pair of new boots. However, they do not mention how scared they used to be every time they went down into the mine, or the fact that alcohol consumption was really high. Many of the workers used to drink to forget the fact that you could lose your life every time you went to work.”

“My grandfather had to walk five kilometers to go to work and another five kilometers to get home,” Delgado says. “After work he would tend his vegetable garden. Of course, this activity helped with the household budget. But I really believe he did it because he had the need to see something grow.”

As a college history major, Delgado went on some nearby digs, accompanied by Juan Aurelio Pérez Macías, the former staff archeologist for Rio Tinto Minera S.A. (the mines’ then-owner) and now an archaeology professor at the University of Huelva. Delgado loved the tangibility of archaeology. “What you find in an excavation is a fact,” he says. “It is the truth. People who write history based on documents call us cacharreros, pottery dealers. And we call them library rats.”

After graduation—he’s now finishing up his doctoral dissertation—Delgado worked for a company that did archeology at construction sites. Seven years ago, he was hired as the director of the Riotinto Mining Museum, which is housed in the hospital where he was born.

IRONICALLY, DELGADO HAS NEVER EXCAVATED in his hometown. Although he has dug elsewhere in the Pyrite Belt, archaeologists have been denied access to Riotinto by the landowners and local government officials since 1993. Still, Riotinto was a fertile excavation site from the 1960s through the ’90s. Delgado’s mentor Pérez dug there for twenty of those years. Pérez uncovered lamps, domestic pottery, statues, amphorae, and metal objects such as buckets, safety pins, and mirrors. Below that, he also found Phoenician artifacts. As a result of those three decades of systematic digging—plus a century of more casual finds—the Riotinto Mining Museum has an extensive collection, including 900 pieces of glassware and 500 Roman-era iron hammers. (“I managed to recover 70 Roman hammers from people’s homes just by convincing them that the museum was a much better place for those pieces,” Delgado says. “I would not have been able to achieve that if I was not from here.”) This gives Delgado and Pérez abundant research material.

Much of their research centers on ancient metallurgy. But Delgado has also used physical evidence—lamps, tools, household utensils—to reconstruct the lives of Roman miners. During our interview, he ticks off “a normal day in the life” of such a worker: “Really early, they would get up and have breakfast, which would consist of a purée made mainly of wheat and bread, or posca—water, vinegar and wine—with some cheese and bread,” he says. “They would grab their lamps and tools and would head up to the mine to excavate for minerals.” The work was exhausting—the museum’s collection includes a Roman hammer that weighs 16 pounds. And the air was toxic, Delgado says, even above ground. Studies of a crematory oven from that era point to an outsized infant-mortality rate. “It was a highly sulfuric environment,” he explains, “so any small child who was affected by asthma or any other respiratory problem could die very quickly.”

Lunch often included a salty fish sauce to balance out their high-potassium diets. Afterward, the miners would “keep working until about four or five p.m. or until the lamp had extinguished,” Delgado says. “Then they would go back home, and then to the public baths, where they would get clean and spend some time with friends. They would have some wine because, even though in Roman times they already had beer, it was not considered elegant to drink beer.”

Delgado and Pérez are passionate about dispelling the notion that all Roman miners were slaves. Evidence from Riotinto’s graves shows many workers had last names, which meant that they had been free men. Delgado worries that the popular conception comes from films like Barabbas, the 1961 classic in which the title character, played by Anthony Quinn, is sentenced to work in Sicily’s sulfur mines—shackled, beaten, never allowed to see daylight. Director Dino De Laurentiis’ hellish scenes “are iconic images that stick in people’s heads,” Delgado says.

Pérez describes the Roman settlements at Riotinto as, in some ways, unextraordinary. “The standard of living would have been very similar to any other Roman town,” he says. “The population was not just composed of slaves but of citizens who had purchasing power to buy the best Roman products.” There were slaves, too, Pérez adds, “but a slave could have been a teacher, or a smelting technician who would have been paid for his work. Although he would still depend on a master, he would have had money and savings.”

For the slaves who were condemned to the mines, Delgado says life was not unlike the scenes in Barabbas. “They would be chained at the neck,” he says, “and their working day would be determined by how long their lamp would last, about 11 hours. They would be woken up really early in the morning. They would be fed a very strong posca to hydrate them and make them drunk, because if they were a bit drunk they would not be as conscientious of their situation. They would also be fed some bread and they would probably not get anything else until the following day. They would feed them enough to be able to go through a working day, but not enough to put up resistance.” Human bones found in slag piles show that enslaved miners were not entitled to burials. Instead, Delgado says, “they were thrown out with the slag and the garbage.”

ANCIENT MINING HAS GIVEN THE IBERIAN PYRITE BELT another grim legacy, as is one of the earliest sources of global pollution. In the 1990s, a team of scientists headed by Australian physicist Kevin Rosman analyzed the lead content of a 1.9-mile-long ice core drilled in Greenland. They found “unequivocal evidence” of massive pollution during Roman and Carthaginian times, with Spain emerging as the main source. Seventy percent of the lead in the ice core that dated between 150 B.C. and A.D. 50 had the chemical signature of Riotinto. Lead, a byproduct of silver mining, was used in everything from shipbuilding to winemaking.

Other research dates the damage even earlier. In a study published in 2000, a group of Spanish and U.S. scientists analyzed a 164-foot sediment core from a site near Riotinto. They discovered significant sulfide and heavy-metal pollution going back 4,800 years. “The contamination started pretty much at the initiation of mining,” says co-author Jeffrey Ryan, chair of geology at the University of South Florida. To get the valuable metals, the sulfide ores were burned in large furnaces that released sulfur-rich gases. Most striking, Ryan says, was that pollutant levels didn’t decrease as mining waned. “You’ve taken the rocks from deep in the earth. You’ve pulled them to the surface. You’ve broken them into little pieces. And you’ve exposed the sulfide minerals to the atmosphere,” he says. “When sulfide is exposed to the atmosphere, it reacts with the oxygen to form sulfur dioxide and leaves behind a heavy-metal effluent.”

When Diego Delgado, the Spanish priest, came upon Riotinto in 1556, he reported to King Felipe II, “In this river there is no type of fish nor living creature, and neither people nor animals drink these waters.” Even today, the Tinto and Odiel rivers are poisoned with arsenic and metals, raising concerns about water quality in the nearby Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea.

At the University of Huelva, I talk with mineralogist Reinaldo Sáez Ramos, whose studies combine archaeology and geology. Sáez talks about his work at Cabezo Juré, an ancient copper-mining community just outside Tharsis. “When we did this excavation, we realized that the villagers ate the shells of a particular mollusk,” he says. “After analyzing those shells, we found out they contained zinc, copper, and arsenic in a quantity that was much higher than what it is considered normal.” By studying clamshells throughout the region, Sáez and his colleagues concluded that the nearby Gulf of Cádiz became polluted with heavy metals around 2475 B.C.—just as large-scale mining and smelting were getting underway. The researchers did find a dip in pollution levels 200 years later when mining ceased. No one knows why mining stopped, but tree-pollen levels in the sediment core show that there might not have been any more trees to burn for smelting metals. “One of the main conclusions we can draw is that when a particular area’s development explodes on a big scale, it ends up destroying itself,” he says.

PAUL CRADDOCK, THE RETIRED HEAD OF THE METALS SECTION at the British Museum’s Department of Scientific Research, remembers digging at Riotinto back in the 1970s and ’80s. “It was a full working mine, with the Electrohaul dumper trucks crashing past every few moments,” he says. “We had to be off the site most days by about 1 o’clock because they were blasting.”

Nowadays, Riotinto is a quieter place. The regional population has fallen from 42,000 in 1910 to 18,000 today. But the crash of trucks might return: Cyprus-based EMED Mining has bought the mines and hopes to reopen them in 2011. EMED says it’s working to preserve 12 historic sites, and plans to open some of them to the public.

Whether or not mining resumes, Delgado considers his museum—part of a larger mining park run by the Rio Tinto Foundation—as key to a new economic-development strategy. “This is another side of archaeology: to spread the knowledge of the ancient world and try to improve the conditions of people living in the present time,” he says. “If one is unable to accomplish those two goals, what is it worth to have a museum full of archaeological pieces?”

Delgado knows that not all his relatives have embraced his career choice. His wife would rather he took more vacation time at the beach, rather than running off to an excavation site with Pérez. As for Delgado’s maternal grandfather, who died two years ago: “My grandfather always used to say that he worked really hard so that his children and grandchildren would never have to work in the mine. Then I went to the university to end up in excavations with a pick and a shovel. He never understood that.”