Originally published in Indy Week. Reprinted in 27 Views of Durham (Eno Press).

IF YOU DIDN’T PEEK AT THE NUMBERS ON THE TV INSIDE—where Amendment 1, North Carolina’s marriage amendment, was racking up a 22-point margin of victory—you might have imagined the scene outside Fullsteam brewery in Durham was a celebration Tuesday night. The air was thick with grilled cheese and Korean tacos, punctuated by cheers from Motorco Music Hall across the street and even a rowdy parade. On a patch of grass, the Bulltown Strutters and Blue Tailed Skinks were blowing their trombones and clarinet, shaking their hips and a tambourine, as if the passage to a better world depended on it. My flag boy and your flag boy/ Sitting by the fire/ My flag boy says to your flag boy/ I’m gonna set your flag on fire. Listening to the musicians singing “Iko Iko” made me feel like we were at a secondline jazz funeral, squeezing out every bit of available life at the moment of deepest loss.

We drank strong beer and reminded ourselves how far we’ve come in the past few decades, and how things often get ugliest before the biggest leaps forward. We quoted Martin Luther King Jr.: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” But Lord, we asked in our exhaustion, couldn’t it just bend a wee bit faster? I thought back to the first time I found myself singing festive songs during a moment of defeat. It was 30 years ago. I was sitting in the back of a paddy wagon.

IN NOVEMBER 1981, A COMMITTEE OF NEW YORK CITY COUNCIL was deciding whether to outlaw discrimination against lesbians and gay men. I was dispatched to cover the 13 hours of hearings for three neighborhood weeklies. I was a 21-year-old college student with long hair and a skinny reporter’s notebook, and I was filled with journalism-school conviction that we were supposed to serve as neutral observers of the day’s events.

For two days I took notes as opponents warned of both lawlessness and heavenly retribution if the gay-rights bill passed. They peppered their speeches with what one council member called “enough quotations from the Scriptures for many months of Sundays.” Evangelist Joanne Highley promised a slippery slope: “Give them rights,” she said, “and then there will come the rights of those who want to have sex with animals. And then there will come the rights of those who want to stand alone and have sex with trees.” (An activist jumped up and shouted, “I’m going up to Central Park to cruise a black oak!”)

At the mention of a recent machine-gun attack on a gay bar that left two men dead, Heshy Friedman of the Jewish Moral Committee applauded and chanted, “Good, good.” But there were also brave acts of self-disclosure, most notably by a police sergeant named Charles Cochrane. His very presence rebutted a union official who claimed not to know a single gay cop.

Just before the vote, Council President Carol Bellamy spread her billow-sleeved arms on the dais and quoted William Faulkner’s Intruders in the Dust. “Some things you must always be unable to bear,” she said. “Some things you must never stop refusing to bear. Injustice and outrage and dishonor and shame. No matter how young you are or how old you have got. Not for kudos and not for cash; your picture in the paper nor money in the bank either. Just refuse to bear them.”

The committee voted 6-3 to kill the civil-rights bill. I surprised myself by standing up and moving toward the front of the chambers. Protesters were forming a circle on the floor, and just for the night I shed my journalistic detachment. Over the next four hours, we told one another our stories and sang “We Shall Not Be Moved” (of course). We took our own vote on the bill, approving it 26-0. Several council members kept vigil with us, one weeping openly. We were not allowed to use the bathrooms, and finally a police officer told us to leave under orders from Mayor Ed Koch. When 21 of us refused, we were arrested for trespassing.

I GRADUATED AND LEFT NEW YORK a few months later and have lived in North Carolina for the past 27 years. My life here—as a professional, a homeowner, a husband, an AARP member—bears little resemblance to my undergraduate days. Yet watching Amendment 1 roll to victory, I couldn’t help but flash back to 1981.

Why should that be? After all, the intervening decades have taken us far from the culture of “sex with trees.” ACT UP. Rock Hudson. Will & Grace. Holocaust memorials. Gay-straight student alliances. Civil unions. Philadelphia. Barney Frank. Lawrence v. Texas, which legalized consensual gay relationships. Ads for JC Penney and McDonald’s. Ellen DeGeneres. Anti-bullying campaigns. Rachel Maddow. “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and its repeal. Elton John. Craigslist. David Sedaris. “It’s Raining Men.”

In many localities, anti-discrimination laws feel old hat. Ten countries and eight U.S. states have voted to marry same-sex couples. Every poll, indeed every conversation, shows that we are one generation away from when homosexuality will shed its political relevance. President Obama, Vice President Joe Biden and Education Secretary Arne Duncan are just the latest prominent officials to throw their support behind marriage equality.

In Durham, where I live, lesbians and gay men are so fully integrated into civic life that sexual orientation (at least to me) feels like an afterthought. My friends, who are overwhelmingly straight, think of my husband and me not as a gay couple, but as a couple. My election precinct voted 95 percent against the amendment. Even my Republican friends opposed the measure, and went out of their ways to tell me so.

Given the relative ease with which I navigate my world as a gay man, I’ve been trying to understand my feelings over the past few weeks, which run less toward anger or fear and more toward weariness. It’s not about Amendment 1 in particular: With notable exceptions, the homophobic rhetoric has been relatively muted this time around. Rather, it’s about the corrosive effect of three decades of adulthood in which I’ve never once assumed that I’d ever be entitled to the most basic rights of citizenship.

Last year in Massachusetts, a gruff-voiced judge signed a waiver of the three-day waiting period normally required for marriage there. The courthouse employees congratulated us as we left the building. But even after a town clerk signed our marriage certificate, we didn’t acquire a single one of the 1,100-plus federal rights given to opposite-sex couples, and our wedding was functionally invalidated when our plane landed in North Carolina. (I joked to my mother that she has a legal son-in-law in her home state, but I don’t have a legal husband in mine.) We have a passel of notarized papers that might or might not help us in the event of a medical catastrophe. But no document will give us, for example, automatic inheritance or spousal Social Security benefits.

Surely, every gay man or lesbian copes differently with the knowledge that the liberties that form the very essence of American democracy remain outside our grasp. For me, the mechanism is something akin to journalistic distancing. When I’m reporting on a story—talking with Louisiana oystermen after the BP oil spill, or watching residents tear down an abandoned house in a Detroit neighborhood—I am fully engaged in the moment, but through a lens of otherness: This is your world. It is not mine.Other journalists put down that lens when they come home. I never fully do. I attend a friend’s heterosexual wedding; talk at a party with someone who volunteers with his son’s Boy Scout troop; or receive an invitation to donate blood during a drive—and find myself viewing all those experiences as outside to my own. Then I generalize to other things, because it has become a habit. This is your world. It is not mine.

This sense that many of these basic rituals are available to others but not to me can’t help but alter my relationship to civitas. Self-identifying as American is predicated on some elemental expectations: I can bind my financial life to another’s. I can volunteer my time to help foster our community’s youth. I can volunteer my healthy blood to save a life. Take away these basic assumptions, and patriotism means very little. Funny, but I don’t get angry when I think of this, or even sad. It just is.

Multiply me by a few million, and think about how much civic energy is squandered as a result.

ON ELECTION MORNING, I LEFT MY HOUSE at 4:30 a.m. and walked through my neighborhood toward downtown. In yard after yard, I passed blue-and-white cardboard signs opposing the amendment. A hand-painted sign nailed to a telephone pole said, “NO ON ONE.”

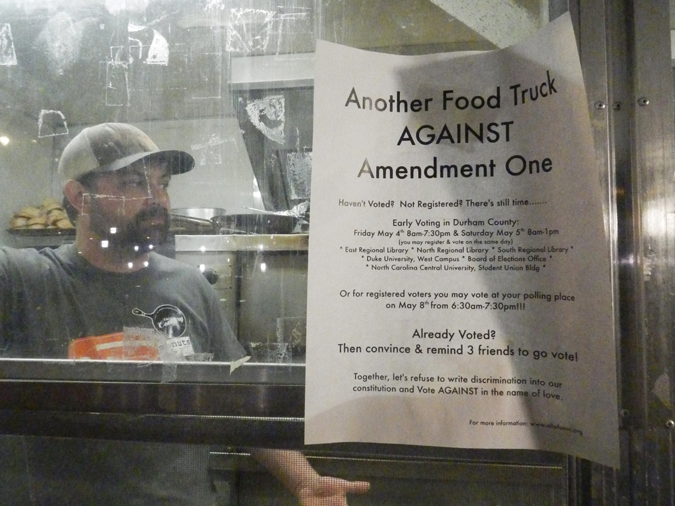

Many of my neighbors had arrived at CCB Plaza before me. The local NBC affiliate was filming its early-morning show there, featuring everyone from Wool E. Bull to the North Carolina Central University marching band to the Monuts doughnut tricyclist. The Strutters and Skinks were there as well, jamming off-camera. The Only Burger and Pie Pushers trucks slung breakfast; the latter displayed a handbill saying, “Another Food Truck AGAINST Amendment One.” A couple dozen Durhamites holding anti-amendment banners and picket signs formed the backdrop for the two-and-a-half-hour broadcast. Durham’s consensus was evident, and it was thrilling.

This has been the redemptive aspect of this struggle. I have never seen a community mount such a forceful, unified, creative response to a collective threat. I have never had so many neighbors tell me, “Your battle is mine too.” The results of Tuesday’s election might solidify the sense of otherness with which I view my state and country. But my patriotism to my city has never been stronger.