At the Republican National Convention, Ron Paul delegates find dissent is unwelcome within the party ranks.

Originally published in Indy Week.

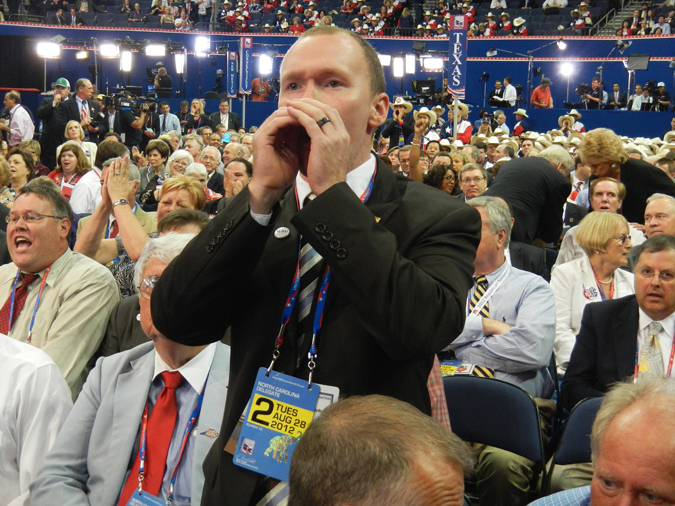

Daniel Rufty, a delegate from Charlotte, called for a formal voter after 10 Ron Paul supporters from Maine were unseated. Rufty’s calls went unheeded. Photos by Barry Yeoman.

IT WAS JUST A FEW YEARS ago that Bret McGraw began his political conversion. The 30-year-old cook, who lives in Durham and works at Whole Foods Market, once considered himself a liberal. In 2008 he voted for Barack Obama, a decision he has come to regret.

“I’m almost ashamed to say it,” he told me last week, reflecting on that vote. We were meeting in Tampa, on the eve of the Republican National Convention, where McGraw was a delegate pledged to Texas congressman Ron Paul. “I’ve never seen a president so blatantly say one thing and then do the complete opposite.”

Our lingering presence in Afghanistan; the continued operation of Guantanamo Bay; the signing of a bill authorizing indefinite military detention without trial—this was not how McGraw imagined an Obama presidency.

Even before 2008, McGraw’s younger brother had told him about Paul, the 77-year-old physician whose swashbuckling libertarianism has galvanized a large and devoted following. McGraw began reading articles and watching YouTube videos, learning about what Paul calls the dangers of central banking and a 14-figure national debt. “It was like someone throwing ice water on me,” McGraw says. “He seemed to be telling me things that were almost like a forbidden fruit in the garden of knowledge.”

Among Paul’s messages was that his supporters should become part of the electoral process. If they showed up at Republican precinct and county meetings—the sparsely populated bottom floors of the U.S. electoral system—they could climb their way up until they became RNC delegates. It’s the same strategy the religious right successfully used in the 1980s and ’90s.

McGraw hadn’t known such a system existed. “I thought it was some sort of mysterious Babylonian secret,” he said. He began attending county, then district and state meetings until he landed a spot representing North Carolina’s 6th Congressional District at the RNC.

That’s how a political newbie—who plays in two metal bands and once sold a painting called “Muppet Road Kill”—found himself a Paul delegate in Tampa last week.

He wasn’t alone. Of North Carolina’s 107 RNC delegates and alternates, roughly one-fourth were loyal to Paul—a far greater proportion than the 11 percent of the vote Paul received during the state’s Republican primary, thanks to deft grassroots organizing. Even though some of those delegates were pledged to other candidates, they nonetheless hoped to carry Paul’s libertarian message to Tampa.

“I like talking to people who disagree with me,” McGraw told me that Sunday. “I try to take the opportunity to have insightful discussion.” He knew his week would be tightly programmed—and not with the chewy conversations he craved. “I was disappointed to learn that the majority of time here for me is going to be parties and Kid Rock performances and Lynyrd Skynyrd performances,” he said.

For McGraw—and for all of North Carolina’s delegates loyal to Paul—the next four days would provide an up-close view of how American presidents are nominated. They would see how crisply the Romney-Ryan campaign tried to stage-manage the message voters received during the RNC. And they would learn what happens when dissenting voices like their own try to get heard.

EACH MORNING, NORTH CAROLINA’S DELEGATES held a pep-rally breakfast at their hotel in St. Petersburg, sponsored by a different corporate donor. (The Democrats do the same.) They listened to a parade of GOP celebrities: New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, evangelical activist Ralph Reed, Mitt Romney’s son Josh, former tea party candidate Herman Cain. This was often accompanied by inspirational words from state party chairman Robin Hayes, a former congressman from a prominent textile-manufacturing family in Concord.

“President Obama is doing everything he can to turn the American Dream into the European nightmare,” Hayes told delegates Monday, the day before the convention opened.

As Monday’s breakfast was winding down, delegate Daniel Rufty raised his hand. It was only Day 1, but he already had something urgent on his mind.

A 26-year-old Army veteran from Charlotte, Rufty had begun questioning his own youthful view of war—which he described, with some embarrassment, as “bomb everybody”—while undergoing rehabilitation for a knee injury at the Warrior Transition Unit at Fort Jackson, S.C. There, he met soldiers dealing with emotional scars from the battlefield. “These soldiers are put in moral predicaments that no one should go through,” Rufty realized. “The people we are bombing have friends, children, grandchildren.” He found himself drawn to Paul’s belief that “unconstitutional, undeclared wars” were bankrupting America and fostering global resentment.

Still, Rufty believed that Rick Santorum had the best chance to stop Romney, whom he considers “just like Obama.” At his district convention, Rufty won a spot as a Santorum delegate. Now, with Pennsylvania’s former U.S. senator out of the race, he planned to vote for Paul.

Today, though, he was upset by two recent developments at the RNC. One was a series of proposed changes in the party’s rules that seemed designed to keep insurgent candidates like Paul from gaining traction. The other was the GOP’s decision to unseat 10 Paul delegates from Maine because of what the national party called “serious credentialing, ballot and floor security issues” at the state convention.

Rufty stood up at the breakfast meeting. “I have a friend in Maine,” he told the delegates. “It’s his first time getting involved in the party. And he was uncredentialed two days ago. He paid for his hotel. He paid for his flight.”

Rufty’s friend was being replaced by a Romney delegate. “I find it really disgusting. I think it’s a kind of a stomp on our democratic process.”

“That’s not exactly the correct story,” said Ada Fisher, a delegate from Salisbury and a national committeewoman. “They had a hearing and they made a decision. You can talk about it, but you are not going to change it.” Fisher didn’t explain why the delegates were unseated. “But it was discussed and I thought it was fair.”

“Keep your eye on the prize,” said Hayes, the state GOP chairman. A unified party, he explained, was necessary to win the election. He didn’t want to see a rebellion within his own ranks.

“There is fruitful gain in this,” Rufty countered. “We can vote down the credentials report and open it up for the discussion at the convention.”

“I would not do that,” said Hayes. “I reject that idea. It’s not really productive.”

“We’re the delegates,” Rufty said, half under his breath.

Hayes was not happy to have a fractured delegation. But he agreed to hold another meeting that afternoon to discuss the proposed rules changes.

That’s when any semblance of unity dissolved.

HAYES OPENED THE AFTERNOON MEETING with another appeal for solidarity. “This late in the game, if you don’t remember anything else, remember: Support your leadership,” he said. “If you think I’m being heavy-handed, I am.”

Nor did Hayes want this meeting made public; it was a “family discussion,” he said. A Paul supporter videotaped it anyway, and I negotiated to stay when Hayes ordered me to leave.

The surprise guest at the meeting—to Hayes’ chagrin—was Morton Blackwell, a former Reagan White House staffer from Virginia who now sits on the Republican National Committee. Blackwell opposed the rules changes. He said they were designed to concentrate power in the hands of establishment candidates like Romney and make it “much more difficult for anything to rise from the bottom to the top.”

Blackwell told the North Carolinians that one “horrifying” new rule would allow presidential candidates to “disavow and remove” delegates chosen by their own state parties. According to a Romney attorney, the purpose was to prevent activists from packing state conventions and picking up delegate seats to which they were not entitled. But that’s not how Blackwell viewed it. He believed the new rule would allow the nominee to snatch delegate seats away from local volunteers—and turn them over to wealthy campaign donors. In effect, the nominating process would be turned over to the highest bidders.

“Our grassroots activists, who were newly active because they wanted to participate in the party, are going to be infuriated,” he said.

Another proposal, which Blackwell called “a disaster,” would allow national committee members to change the party rules between conventions with a 75 percent vote. Currently, only delegates can change the rules every four years at the national convention. GOP officials say they wanted more flexibility: “Four years is a long time,” party spokeswoman Kirsten Kukowski told CNN.

But Blackwell saw the new proposal as yet another attempt to concentrate power in the hands of the Republican establishment—stripping grassroots volunteers of any real say in how their party is run. “It is a power grab which opens the door to many future power grabs,” he said. Because he has “the power of the purse,” Blackwell said, “the national chairman can get a three-quarters vote for anything that he wants. On a whim, he can get it.”

After Blackwell finished, Hayes asked him to leave—then scolded whoever had invited the Virginian without asking permission. Hayes again urged the delegates to support the rules changes. “The discussion was fair,” he said. “All sides were heard. Compromises were made. So back to the issue at hand: defeating Barack Obama.”

Hayes was preaching now, his voice reaching fire-and-brimstone volumes. “Folks, you elect a leadership to lead,” he continued. “I have gotten to know, over a period of years, [Republican National Committee chairman] Reince Priebus. He brought this party back from the grave. With hard work. With perspiration. With incredible dedication.” Challenging the rules, Hayes warned, would “undo what he has done.”

Jeffrey Palmer, a soft-spoken Paul alternate from Durham, raised his hand. “I really respect you,” he told Hayes. But giving veto power to national politicians could be devastating. “It’s the lifeblood of this party that we bring new people in,” Palmer said. “This is grassroots versus people at the top. And for someone to work that hard, go through the process, and then to have a presidential candidate come in say, ‘Uh, no, we’d rather have my crony over there, my fundraiser over here, my lawyer over here, to fill those slots, so they can ram through my position,’ that’s just wrong.”

As Palmer spoke, Hayes walked over and put an arm around his shoulder. But the chairman didn’t concede his point. Nor did the delegation’s pro-Romney majority, which—after an hour of conversation—voted to side with the leadership.

WHEN YOU SPEND A WEEK TALKING with Ron Paul supporters, as I did in Tampa, conventional notions of left and right start to evaporate. The congressman’s fundamental message is that government does more harm than good: It warps the economy, restricts civil liberties and imposes our national will in ways that invite “blowback” from around the world.

Paul’s economic philosophy says a free market transmits signals, in the form of interest-rate fluctuations, which allow people to make rational decisions. When a central bank intervenes in that market, he argues, the signals get jammed and the economy goes haywire. That’s why Paul wants to abolish the Federal Reserve System, which his website says “fuels our economy’s boom-bust cycle and has helped devalue our dollar by over 95 percent.”

Paul takes aim at many—but not all—restrictions on individual freedoms: airport searches, the PATRIOT Act and laws governing what we put into our bodies. “Personal liberty, when it returns, once again you’ll be able to drink raw milk,” he said at a pre-RNC rally I attended at the University of South Florida’s Sun Dome. “You’ll be able to make rope out of hemp… You will be allowed, without a government permit, to buy nutritional products, when you please and what you please. No longer will government assume they have the responsibility of protecting you against yourself.”

Paul opposes abortion rights, saying the unborn also deserve liberty. He calls the right to own firearms “God-given.” And he wants to eliminate chunks of the federal government, including the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Education. He told CNN in January that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 “destroyed the principle of private property and private choices.”

His leeriness of war attracts young adults like McGraw and Rufty. But Paul attracts older voters too, including Rebecca Christenbury, a 91-year-old alternate delegate from Charlotte.

“I can remember living in a free country,” Christenbury told me when we met last week. “You were raised to be a socialist. I was raised to be free. We had no sales tax. We had no gasoline tax.” She paused. “We were free.”

As an adolescent, Christenbury’s mother told her that President Roosevelt would fix the country with his New Deal. “Mother, that’s not right,” she recalled saying, “to take money away from one person and give it to another person.”

Christenbury’s distrust of government eventually led her to the virulently anti-communist John Birch Society, which was founded in 1958. (Among the targets it called “Com-symps” were President Eisenhower and civil rights leaders.) Reading the society’s newsletter, Christenbury learned about Paul. She has been a fan ever since.

Like the rest of North Carolina’s pro-Paul delegates, Christenbury is personable and sympathetic, even though I don’t share many of her views. But Paul also draws supporters from the social fringes. These include white supremacists who read race-baiting articles in Paul’s newsletter during the 1980s and 1990s, which he claims not to have written and has since disavowed. He doesn’t welcome these supremacists, but he has embraced people whose brand of libertarianism runs toward the insurrectionist.

The Saturday before the RNC, I attended an unsanctioned festival of Paul enthusiasts just outside Tampa. There I met Larry Pratt, founder of Gun Owners of America, a group that considers the National Rifle Association too wishy-washy. (Paul touts the group’s support.)

“The Second Amendment says the gun should be pointed at the government,” Pratt told me, with the county sheriff serving as the “wall of interposition.” He talked about an Indiana sheriff, Brad Rogers, who threatened to arrest Food and Drug Administration agents for inspecting a farm that sold raw milk possibly linked to a bacteria outbreak. If a sheriff is willing to deputize his armed constituents, Pratt said, “the feds can be put back in their box.”

When I told several North Carolina Paul loyalists about that conversation, they distanced themselves from what they called the extremist edge of Paul’s big tent. “The Paul people are peaceful people,” said Rufty. “They’d rather fight the intellectual revolution.”

BY TUESDAY’S OPENING SESSION of the RNC, the proposed rule changes had been scaled back. Presidential candidates would not be allowed to handpick their own delegates after all. But the national committee could still amend its rules without the delegates’ approval—and that, to some Paul (and tea party) supporters, made the compromise unpalatable.

The convention would vote on these new rules. But first it had to approve or reject the decision to unseat the original Maine delegates. “All those in favor will signify by saying ‘aye,'” said national committee chairman Priebus.

The hall erupted with ayes.

Priebus smiled. “Those opposed, ‘no,'” he said.

This time it erupted with shouts of “no.” Standing on the floor, I couldn’t tell which side sounded louder.

“In the opinion of the chair, the ayes have it,” Priebus announced, officially unseating the original Maine delegates.

Under the RNC’s rules, any delegate can call for a formal vote, in which each side stands up to be counted. Rufty, the Army veteran, jumped up, cupped his mouth and shouted, “Division!”—the official word for this procedure. He was joined by delegates from around the country. When Priebus ignored their calls, much of the Texas delegation stood and started chanting, “Point of order! Point of order!” The majority drowned them out with a counter-chant of “U.S.A.! U.S.A.!”

Rufty shouted again. Hayes, the state party chairman, turned to him.

“It’s over,” Hayes said. “Don’t embarrass us.”

“I’m calling for division,” Rufty said.

“We don’t need division,” Hayes replied.

“It’s not debatable,” Rufty said. He was correct. But the convention rolled along.

An identical sequence happened with the rule changes: a too-close-to-call voice vote, shouts of “Division,” drowning chants of “U.S.A.,” and a chairman (this time House Speaker John Boehner) who didn’t acknowledge the dissent.

As the commotion raged on, Bret McGraw fell silent. The Durham cook had assumed this was how conventions worked. Still, he was disappointed. “It isn’t just disappointment in the Republican Party,” McGraw told me. “It’s disappointment in America. It’s a bit of betrayal, even with the expectation.” He wondered why the GOP, which needs a broad coalition to win this election, was so aggressively alienating one of its constituencies.

“It’s so confusing to me,” he said.

Later, Rufty would show me a video someone had taken of the teleprompter during the rules vote. It said, in part, “In the opinion of the chair, the ‘ayes’ have it.” Speaker Boehner was just reading a preordained outcome.

THE ROLL-CALL VOTE NOMINATING the presidential candidate is the raison d’être for any national political-party convention. It’s also one of the emotional high points. Each state gets its turn in front of the cameras. A spokesperson offers a poetic tribute to his or her home state. Then that delegation’s votes are officially recorded.

The roll call came a few hours after Tuesday’s fractious rules vote. At least now, the Paul supporters figured, their votes would count.

“Madame Chairman, the great state of North Carolina, where the weak grow strong and the strong grow weak, was Tar Heel blue in 2008,” said state party vice chairman Wayne King. He passed the microphone to Justin Burr, a young state legislator from Albemarle.

“But Madame Secretary, this year North Carolina will be Wolfpack red in 2012,” Burr said. “And we cast seven votes for Paul, and we proudly cast 48—”

“Forty-eight!” the delegates echoed.

“—for the next president of the United States, Governor Mitt Romney.”

Daniel Rufty grimaced when he heard the vote total. Of North Carolina’s 55 voting delegates, only seven were formally pledged to Paul. But there were also four Paul supporters among the delegates pledged to Santorum and Newt Gingrich. Rufty was one of them. No one had polled those delegates to learn how they wanted to vote, now that their candidates had dropped out of the race. Party leaders automatically transferred all the non-Paul votes to Romney.

By Rufty’s calculation, he had spent thousands of dollars, eating Ramen noodles and raising money through a crowd-sourcing site—just to have his vote cast, without his consent, for the candidate he opposed. “I didn’t vote,” he said. “That’s what I was here to do.”

“How do you feel?” I asked.

“Disgusted, stomped on, cheated. Those are the words that come to mind. We played by the rules. They bent their rules.”

The Paul supporters I interviewed generally felt that this was not a deliberate attempt by North Carolina’s Republican leaders to quash votes. They attributed it instead to inattention. But given how marginalized they already felt, the undercount hit a raw nerve.

When I asked Hayes, the state chairman, about those four votes, my question seemed to hit another nerve. “I’m always here. My phone is always on. If they wanted to talk to me, and they didn’t, whose fault is that?” he asked. “It’s not like I’m hiding.”

THE NORTH CAROLINA BREAKFASTS CONTINUED. At Wednesday’s, sponsored by Food Lion, U.S. Senator Marco Rubio of Florida accused President Obama of fomenting class resentments. “He tries to convince Americans that the reason they’re worse off is because other people are too well off,” Rubio said. “He tries to convince people that the way people in this country become rich is by making other people poor.”

The thunderous reception that Rubio received—followed by a race to the door to pose with him for pictures—gave the impression of a delegation united to defeat Obama. Still, the fault lines were evident.

“They’ve stacked the decks so high that the grassroots will be shut out,” said Mattie Rose Crowder, an alternate delegate (and Paul supporter) from Orange County. “It’s destroying the stability and integrity of this party.”

The Romney supporters, for their part, felt angry that Paul’s allies were tilting the convention off-script. Even being seen with a Paul delegate became grounds for suspicion. On the convention floor, two North Carolina Romney delegates confronted me. They had noticed me talking with the other camp, and this proved to them that I was not really a reporter. Rather, I was a pro-Paul infiltrator who had fraudulently scored press credentials. “You’re trying to disrupt the convention,” said Asheville delegate Bill Lack. “You don’t understand how conventions work.” (In his hometown paper, the Citizen-Times, Lack had likened the RNC to a Broadway show performed for the nation.)

Later, when I was trying to interview another Romney delegate, Lack blocked my access. The convention floor was packed, and I physically could not pass him without his consent. “He’s not really a journalist,” the Asheville delegate announced. When others tried to intervene on my behalf, Lack scowled silently. But he still wouldn’t let me through.

Asheville’s Bill Lack accused me of being a pro-Ron Paul infiltrator who was “trying to disrupt the convention.”

ON THE LAST NIGHT OF THE CONVENTION, the delegation’s floor seats were filled almost exclusively with Romney supporters. This was the nominee’s big moment, and many of the Paul supporters had given their floor passes to backers of the former Massachusetts governor—a “goodwill gesture,” said Durham’s Jeffrey Palmer.

With the exception of Clint Eastwood’s vulgar conversation with an imaginary President Obama, it was an evening of momentum: a stage full of Olympic athletes. Rubio’s tribute to his immigrant father. And then Romney, who left delegates snickering by saying, “President Obama promised to begin to slow the rise of the oceans and heal the planet.” The laughter transformed into cheers and whistles with the nominee’s follow-up line: “My promise is to help you and your family.”

Then 120,000 balloons, some the size of beach balls, wafted down from the rafters. For a few moments, the delegates became little kids. Even my accuser, Bill Lack, who had worn a sourpuss face all week, cracked a smile (though not at me).

Afterward, the North Carolinians held a poolside celebration at their St. Petersburg hotel. Around 2 a.m., I caught up with Daniel Rufty standing alone near the bar. He wasn’t exactly feeling the spirit.

“We criticize other countries for manipulating the vote, and then do it openly,” the Charlotte veteran told me. “All this stuff I thought—you vote, and your vote is counted—it’s a façade. It doesn’t happen.” But Rufty added that his RNC experience has inspired him to become more politically active. “It gives me the fuel I need to be the change in the world,” he said. “I need to be the change I want to see in North Carolina.”

https://youtu.be/UW_rD4Liuh8

Daniel Rufty calling for a point of order at the 2012 RNC. Video by Barry Yeoman.