Suffering from advanced-stage ovarian cancer, Sue Otterbourg declined aggressive treatment to spend her last months living fully. Why can’t more people do the same?

Originally published in Indy Week.

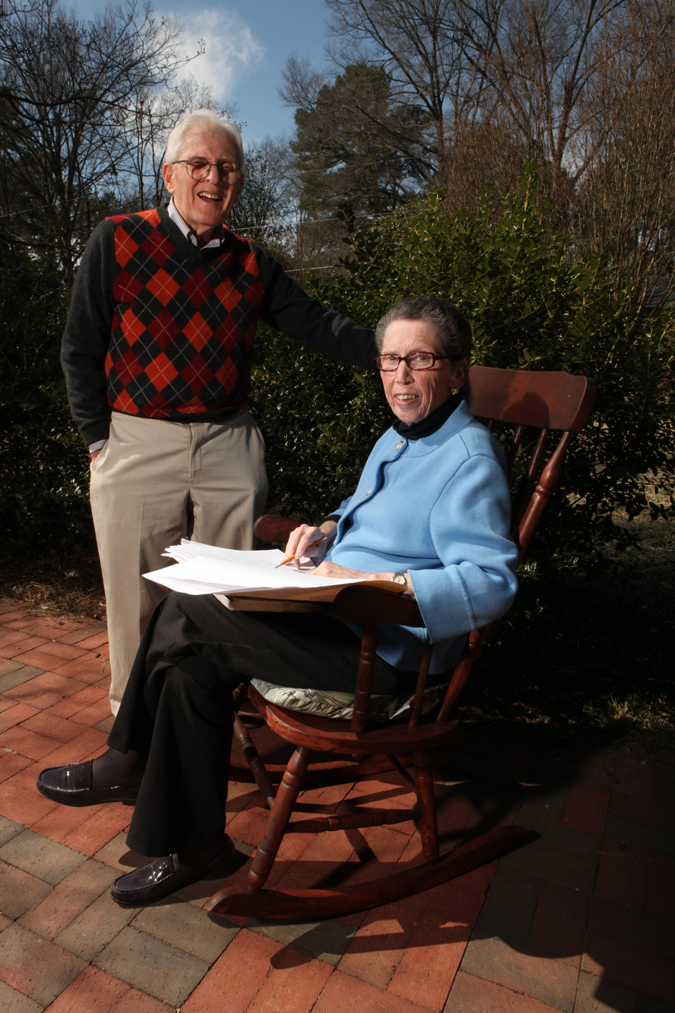

Sue Otterbourg at home with her husband Bob. “She saw herself as a full partner with her medical team,” says Jay Foster, her son’s friend and a hospital chaplain. Photo by Angie Smith.

THE FIRST TIME I MET SUE OTTERBOURG, she greeted me at her front door in Durham’s Forest Hills neighborhood dressed as anyone would for a business meeting: earrings, wristwatch, lipstick, stylish glasses. She led me into her living room, where two armchairs flanked a fireplace, and handed me a résumé that chronicled her impressive career as an educator. Her husband Bob, a writer, made us tea as we settled in to talk. At 76, she looked gaunt, like someone who had lost too much weight too quickly. But her hair was brushed back to flatter her slender face, and her manner was brisk and efficient. Otterbourg had one more month to live, and there was still work to be done.

A year earlier, she had been diagnosed with advanced-stage ovarian cancer, which by then had metastasized to her lungs. The news blindsided Otterbourg, who had rarely been sick in her life. Her oncologist at Duke University, Laura Havrilesky, says the standard treatment would have been a combination of surgery and multiple-agent chemotherapy, with the hopes of a brief remission. “We could have eked out a bit of time,” says Havrilesky—a few extra months or, if they were extremely fortunate, two to three years. But the side effects would have been all-consuming. Otterbourg was having none of this. No invasive operations. No debilitating therapies. Her care would focus entirely on comfort, she insisted, so she could spend her remaining time living fully. “It was very unusual,” Havrilesky says of her patient’s request. “That’s not where I would usually go with this. But given that she had a strong conviction, we had to meet her where she wanted to be.”

I was visiting Otterbourg because she seemed to embody the growing movement to re-envision the end of life—to give seriously ill patients the right to limit or decline aggressive (and often futile) treatments. Those who wanted to use feeding tubes or intensive chemotherapy still could. But patients could also opt out, and instead devote their last months to visiting with loved ones, pursuing enjoyable activities and tying up spiritual and material loose ends. Either way, a care team would keep the pain and discomfort under control and provide whatever support the patient and family needed.

Studies show that Americans want more control over their last months, valuing both symptom management and things like resolving old conflicts. New research even suggests that patients live longer by rejecting certain “life-lengthening” treatments. But even as the culture moves forward, we still have not reached the point at which Otterbourg’s take-charge approach is anywhere near the norm.

The day we met, in February 2011, Otterbourg told me how her diagnosis forced her into a speedy life review. At the oncologist’s office, she thought about her good fortune in spending more than five decades married to the man who had enthralled her at 22. She thought about how proud she felt of her two children and how much she loved their partners. She thought, too, about her grandchildren. “I’m just as lucky as can be,” she recalled feeling. “So why should I try to up it, when I know what I’ve had?” In whatever time she had left, Otterbourg planned to put her life in order—a process that would come to include travel, financial planning, tough family discussions, a change in treatment plans and the incremental acceptance of her mortality.

IN 2010, THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE published a study that fundamentally challenged how we view end-of-life care. Many of us imagine two opposing options for very ill patients: We can either extend their time or improve the quality of their lives, but not both. But that’s a false dichotomy.

The study, by Massachusetts General Hospital oncologist Jennifer Temel, examined what happened when lung cancer patients started receiving “palliative” or comfort care shortly after diagnosis, in addition to their usual treatment. Those who received early palliative care were less likely to choose aggressive treatments such as chemotherapy toward the end. But they lived, on average, almost three months longer: 11.6 vs. 8.9 months.

The results didn’t surprise physician Diane Meier, director of the New York-based Center to Advance Palliative Care. Less aggressive treatment means fewer days in the hospital—”and the data is abundantly clear that hospitals are quite dangerous for the seriously ill,” she says. Those receiving palliative care suffered less depression, which Meier calls “an independent predictor of mortality.” And rejecting long-shot treatments makes patients “the captains of their own ships,” she says, giving them “a motivation to keep fighting.”

While doctors have long known this from observation, Temel’s findings offered solid evidence. “The study was really important,” says James Tulsky, director of the Duke Center for Palliative Care. “It was a randomized controlled trial at a prestigious institution. It was done well. And it showed a longevity benefit to palliative care, which was huge.”

Doctors such as Tulsky and Meier are promoting a more sanguine acceptance of mortality. They consider dying the final stage of living—not something to stave off when it’s inevitable. This acceptance, when it happens, allows families to find meaning, and sometimes even sweetness, in a loss.

It turns out that’s what many terminally ill people want. Karen Steinhauser, a medical sociologist at Duke, has asked patients, families and professionals to define a “good death.” Steinhauser discovered several common threads. Patients want to be free of pain. They want to be kept clean and maintain their dignity. They want to be part of a clear decision-making process. They want to feel a sense of completion to their lives. They want to give back to others. And they want to be affirmed as whole people, not just as dying patients—”to know that my story, my life mattered,” Steinhauser says.

Sue and Bob Otterbourg at home in 2011. The couple traveled extensively in Sue’s final months. Photo by Angie Smith.

In the three decades since Congress approved a Medicare hospice benefit, we’ve lurched incrementally toward making this possible. Tens of millions of foundation dollars have gone into training health care professionals and promoting better care. Hospice use is up. So is the availability of palliative medicine at hospitals, even for patients still undergoing curative treatment. In 2006, the American Board of Medical Specialties recognized hospice and palliative care as a legitimate subspecialty. Around the country, innovative programs are addressing patients’ emotional and spiritual needs and helping them contemplate and document their medical preferences.

President Obama’s 2010 Affordable Care Act didn’t specifically address end-of-life issues, but experts say it will have an unintentional positive impact. For example, it penalizes hospitals that have excessive readmissions of discharged patients. Some institutions are looking to palliative care as a way to prevent those readmissions.

“We’re at a crossroads and we’re at a moment of incredible opportunity,” says Tulsky of Duke. “We are much further than we were. And yet we are not where we need to be.”

“YOU WANT SOME GALLOWS HUMOR?” Sue Otterbourg asked me. “I came home from the doctor. I’d gone myself, and I said to Bob, ‘Sit down. You want the good news first or the bad news first?’ He said the good news. I said, ‘Well, the good news is I’m not gonna die of Alzheimer’s.'”

Of course, no one was laughing the day Otterbourg was diagnosed with cancer. After that conversation, the couple went out for what Bob calls “the worst dinner in our married life”—he couldn’t even swallow his food. But bluntness, I learned, was very much Otterbourg’s style. She had lived a life in which achievement, professionally and at home, usually trumped reflection.

“She was always trying to juggle things at a time when a lot of women didn’t work, and there wasn’t a lot of takeout food,” says her daughter Laura. “She got two master’s [degrees] while we were growing up, and was writing grants for the school system and trying to move up in her own career. But that never impacted her interest in what we were doing, and her involvement with our lives. She managed to do everything. I never thought her as superhuman. I just thought that’s what every mother does.”

Otterbourg spent 24 years as a teacher and principal before becoming an educational consultant who helped pioneer the concept of school-business partnerships. In 1992, she and Bob followed their son Ken, a journalist, from New Jersey to North Carolina, drawn by Durham’s intellectual life and small-city feel. Living near a top-ranked hospital like Duke was important to them. “We wanted to age in place,” she said.

In all her decisions, Otterbourg used what loved ones called her analytical gift. “She was a wizard at backgammon,” says Ken. “It’s the same sort of approach to knowing what your play is. My mom had a very soft side. But she had, in the best sense of the word, a brutal side. I don’t mean that as harsh or unforgiving. But she saw with a lot of clarity the way things were going to be.”

No surprise, then, that when she was diagnosed, “she saw herself as a full partner with her medical team,” says Jay Foster, a friend of Ken and the chaplain supervisor at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. “She was not afraid to ask hard questions. She was not afraid to go back and ask a second or third time, ‘What does this mean?’ in an effort to get clarity about what her options were.”

At first Otterbourg wanted no care beyond hospice—a decision she announced to her children with candor. “It was like: ‘This is what I’m doing. Do not tell me otherwise. Do not tell me about anything else,'” Laura recalled.

“It was not well done,” Sue agreed.

“Not her finest execution,” said Laura, who wanted her mother “alive any way possible.” To Laura, that meant fighting the cancer more actively.

Otterbourg learned there was a middle ground. She could undergo single-agent palliative chemo, which would not cure the disease but might slow down its progression and relieve some symptoms. She agreed to try, and for six months the benefits outweighed the side effects. But she received diminishing relief, and the final treatment walloped her with a painful bowel obstruction. “So I decided: Why bother with this?” she says.

Meanwhile, she had a life to live. “We wanted everything in financial order,” Otterbourg said. “That was the first thing.” She and Bob consulted with experts to ensure their documents were up to date, and talked with their children about how to divide their possessions. She met with Foster, the chaplain, to plan her memorial service. Above all, Otterbourg worried about Bob’s transition. So the couple visited a retirement community and picked out the apartment where Bob hoped to live after her death.

Like many terminally ill patients, Otterbourg wanted to stay productive. “She was like a one-woman sweatshop in her knitting and crochet,” says Ken. “God knows how many health care workers over at Duke have something she’s made.”

Bob and Sue Otterbourg, Durham, North Carolina, 2011. “I realized the good life was coming to an end,” he says, “but we tried to continue that without masking it or making believe it’s not happening.” Photo by Angie Smith.

Sue and Bob traveled to Virginia to watch Shakespeare, to the North Carolina coast and twice to New York. “The second occasion, taking a taxi to LaGuardia, I said, ‘Gosh, we’re never going to do this again,'” Bob recalls. “I realized the good life was coming to an end, but we tried to continue that without masking it or making believe it’s not happening.”

In one of the high points of her final year, Otterbourg watched Ken get married. (The date was chosen to accommodate her illness.) “The pictures from my wedding, if you look at her, she’s not a woman who’s gonna be dead in nine months,” Ken says. “She’s a woman who’s fully alive, and vibrant, and living in the moment.”

GENTLER END-OF-LIFE CARE SAVES MONEY, eases depression and potentially extends lives. Yet stories like Otterbourg’s remain exceptional. There is still too much futile treatment—with all the side effects, hospital noise and invasive hardware—and little of the peacefulness people say they want. One of five Americans dies in an intensive care unit, putting their caregivers at higher risk for PTSD. And while hospice usage is now approaching 45 percent, many patients wait until their last week, when it’s too late to reap the full benefits.

One reason is financial: In medicine, the profit center remains in technologies designed to extend life. Another is political, dating back to Sarah Palin’s false claim that Obama’s health care reform would create “death panels” to ration care. The resulting firestorm killed a provision in the Affordable Care Act that would have paid physicians for talking with patients about issues like living wills. Worse was the long-term chilling effect. “Any legislation that has anything to do with palliative care risks being labeled ‘death panels’ and becomes a nonstarter,” says Duke’s Tulsky. “Until that moment, palliative and end-of-life care was a bipartisan issue. With one phrase, Sarah Palin did more damage to our movement than almost anybody had done in the last 15 years.”

What’s more, the cultural and emotional impediments run deep. “We live in a culture that is fairly death-denying,” says Steinhauser, the sociologist. “We say, ‘If I die,’ and not ‘when I die.'” Steinhauser’s grandmother, who was born in Scotland in the 1890s, sewed her own burial shawl as a child, a blunt acknowledgement that we all die. By contrast, today, “everything is set up to stave off mortality,” she says.

Even many doctors, especially older ones, feel squeamish about death. They’re trained to cure diseases, and watching a patient die feels like conceding defeat. They don’t like delivering bad news. They grow attached. So instead they punt decisions to patients and families—”turfing responsibility to the people least capable of taking that on,” says Meier, the New York physician.

Questions like “Do you want us to continue your mother’s antibiotics?” are rarely useful, says Meier. “The [better] question is: What are you hoping we can accomplish with your mother? Very often they’ll say, ‘Can’t you do something about the pain?’ or ‘Is she dying?’—questions that lead you to a real conversation.”

Tulsky says it’s common (and human) for physicians to respond to distress—to relatives who ask, “Doctor, isn’t there anything else?”—with “one more chemo,” no matter how pointless. “We try to teach that there’s a different response to distress, which is empathy. If you sit with someone and you empathize and you listen and you share, you won’t fix it, but neither would the chemo have. But the person will be able to get through it, and that’s the goal.”

RESEARCHING THIS ARTICLE, I MET patients with serious illnesses as well as recent survivors. All of them valued the symptom relief that hospice provided. But when it came to end-of-life aims, their stories differed wildly. “My goal is getting ready to meet my God,” Maude Boykin, a 100-year-old retired teacher in Durham, told me. “I say the Lord’s Prayer every night and every morning. I don’t want my soul lost.”

Boykin, who later died of lung cancer, was also sharing her history with her 19-year-old great-great-nephew, telling him about segregation and the civil rights movement.

In Raleigh, Thomas Goldsmith, an editor at The News & Observer, told me how his father’s last weeks centered around storytelling and music. “It was like Christmas,” he said, “when you sit around and talk.” Richard Goldsmith and his three children would sing together—everything from “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” to “Lulu’s Back in Town”—like they did on road trips 50 years earlier. Meanwhile, employees of Hospice of Wake County visited Richard’s apartment to keep him comfortable. “We were together as a family,” Thomas said, “probably more than we have been in years.”

And Sue Otterbourg was trying to maintain as much normalcy as possible, even in her very last weeks. She shopped for groceries, borrowed books from the library, played backgammon with her son-in-law (and won their last game). She insisted Bob keep writing and visiting his friends—a common impulse, it turns out.

The staff from Duke Hospice “have been like angels,” Otterbourg told me, in terms of controlling her pain. “Two-thirty in the morning, five o’clock in the morning, it doesn’t matter.” What hospice couldn’t restore—what no one could restore—was her physical vitality. “I was a Triple-A energy bunny, and then suddenly I cannot get the energy going,” she said. “This is like wandering in no man’s land.” A week later, with her body noticeably shrinking, I asked Otterbourg what she had been thinking about. “To be honest,” she said, “I’ve been thinking that I would like it to go faster if it’s gonna go.”

And then it went. In March 2011, nine days after our last interview, Otterbourg died before daylight on a Monday morning. It had been a quiet weekend, for the most part, with pizza and videos and Otterbourg drifting in and out of consciousness. At the end, Ken and Laura sat at their mother’s side, encouraging her to go in peace and promising to care for their father.

It was not a storybook ending. Missing from the bedside was her husband. A few hours earlier, Bob had suffered a stroke, and he was still in the hospital when Sue died. He continues to make progress in rehabilitation, and wonders if he should have paid more attention to his own stress during his wife’s illness. “But I wouldn’t have done anything different,” he says. “Sue had a way she wanted to live and die. And that’s what she did.”

Shortly after Otterbourg’s death, I had lunch with Ken. “My parents, in some ways, have lived a really charmed life,” he told me. “They were married for 53 years. They both had good careers. They carved out this rich life, but they’d also had their share of heartbreak. My mom was at peace with all of it at this particular time. That gave her the strength to say, ‘You know what, I’ve had my portion. Would I like more? Yes, but I don’t need any more. And here’s the calculation: By choosing this path, I’ll be happier for a shorter amount of time.’ Success is being able to choose, and she was able to choose. It’s not the choice that everybody would make, but it’s the choice that she got to make. And I think that’s pretty powerful stuff.”