Originally published in Indy Week.

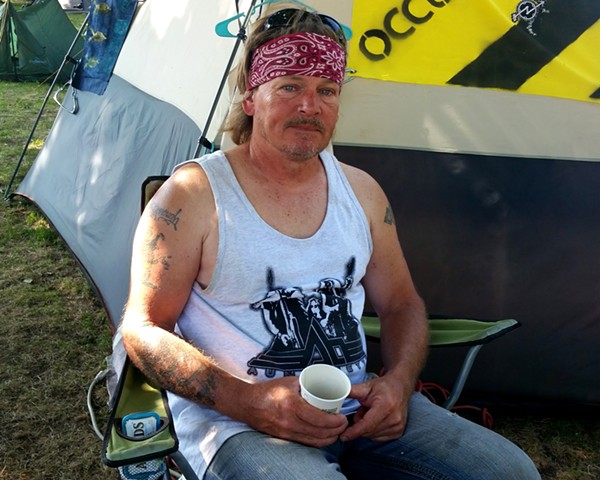

David Guthrie (left) and Coulter Loeb have been part of a leaderless activist encampment in Cleveland’s Kirtland Park. Photos by Barry Yeoman.

I PULLED UP TO CLEVELAND’S KIRTLAND PARK at 11 p.m. Tuesday night. It’s in an industrial corner of the city, where old brick structures sprout vegetation and “for lease” signs—a narrow band of green sandwiched between the railroad tracks and Interstate 90, populated by a family of skunks. “Broken glass lurks,” said a handmade sign taped to a tree near the entrance.

There’s a staircase down from the parking lot. As I approached the field that’s been dubbed “Camp Occupy RNC,” I heard a hoarse voice call, “Mic check!” It was the signal, borrowed from the Occupy Wall Street movement, that a “human microphone” was about to commence, one voice amplified by many in the absence of electronics. The speaker was John Penley, a sixty-four-year-old North Carolinian and one of the elder statesmen of this encampment. He was asking his neighbors to do a better job of properly disposing their garbage.

Just before the Republican National Convention, city officials here made a last-minute decision to open Kirtland Park to campers and to supply drinking water and portable toilets. The park has attracted a few dozen activists inspired by the Occupy movement, many visiting to protest at downtown venues like Public Square. Others have come mostly to live, briefly, in a leaderless, democratically governed community that values music and poetry, conversation, and the free sharing of resources.

The park has also attracted a handful of Donald Trump supporters. The two groups have mingled and even found some shared values.

“I consider this to be a dog park, but for humans,” said David Guthrie, a thirty-five-year-old from South Bend, Indiana, who quit his hotel job in 2012, defaulted on his student loans, sold his car, and has been living modestly (and homelessly) since then. He’s a bear of a man, with a tattoo on his chest of a brain in a jar, and says his activism began with a group of anti-Scientology hackers in 2008. Mostly, though, he considers himself a “Martian anthropologist, exploring as many different subcultures as I’m able to get access to, learning their shibboleths, enjoying their wisdom, and developing my own.” Earlier this month he had been in Vermont attending a Rainbow Family National Gathering.

For Guthrie, the sense of belonging he’s found in Kirtland Park is more important than the protests downtown, where “you’re going to get soundbites and angry conversation,” he said. “If the mousetrap goes off and Public Square is cleared, this is a waypoint where one can find an open forum for dialogue.”

Cleveland is Guthrie’s first GOP convention. By contrast, John Penley has been protesting at national conventions for decades. Described in a 2008 newspaper article as “New York City’s cuddliest anarchist” (he has since moved to Asheville for family reasons), Penley prefers the term “anarcho-yippie,” after the Youth International Party cofounded by his acquaintance Abbie Hoffman in the 1960s.

Penley is a Vietnam-era veteran and an accomplished photographer who has chronicled activism and the counterculture for decades. And he’s an activist himself, protesting issues from gentrification to war. Penley served a year in federal prison in the mid-1980s for trespassing at the Savannah River nuclear-weapons facility, but not before fleeing to, and getting extradited from, Nicaragua. In 2012 he was arrested outside the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, where he was protesting veteran suicides, poor treatment at VA hospitals, and the prosecution of military whistleblower Chelsea Manning.

Demonstrating at national conventions is a time-honored Yippie tradition. “There’s no place else, and no time, when you can get an alternative message out to America like the conventions,” Penley says. The idea of camping at Kirtland Park, though, originally made him nervous. “I was worried that Bikers for Trump”—who had promised an armed response to protests from groups like Black Lives Matter—“would take over this park, and it wouldn’t be a safe place. But that didn’t happen. People are having a good time. We’re getting together with [the pro-Trump campers]. We fed them pizza tonight.”

As our conversation wound down, a talent show was announced, and we assembled in front of a makeshift stage. A fifty-year-old Minnesota electrician named Todd McDonough played country music on his guitar. There was accordion music and drumming, and a young woman played a ukulele tune so beautifully that it made me ache. Someone tried political free-styling. And Guthrie (whom the emcee described as “fucking adorable”) recited his poetry. “What is this thing that nobody owns?” he began. “I believe people grow kinder.”

WHEN I RETURNED YESTERDAY, I learned that McDonough, the electrician/guitarist, was one of those Trump supporters. (A veteran, he appreciates the Republicans’ support for veterans and shares Trump’s belief that it’s too easy for radical Islamists to slip into the United States.) McDonough, who has pale blue eyes and long blond hair held in place by a bandana, had come to the park looking for Bikers for Trump. Instead he found the occupiers.

“It’s been really cool. We’ve had some good debates,” he told me. “I think we want the same things. We can’t be divided into right versus left. We can’t fight each other. We need to come together as Americans and take back our government. It’s a lot easier to take control of people if you keep them divided and keep them in control of themselves.

“I’m glad I ended up here instead of with the bikers,” he said.

“So far, this has been really fuckin’ beautiful,” added twenty-eight-year-old Coulter Loeb. Not only have the occupiers gotten along with the Trump supporters here, but they’ve also gotten along with the police. Some officers visited the park early Monday morning to warn the campers of an approaching storm. “We said thank you and wished them a safe week. They were almost surprised,” Loeb said. “The next morning, they brought us Gatorade.”

That’s not to say everything has been hunky-dory in Cleveland. At the same time we were talking yesterday, eighteen people were arrested downtown in the chaotic aftermath of a flag-burning protest. “This was done in an area designated by the Federal Court as an official First Amendment space,” John Penley wrote on Facebook. “The police were obligated to not only allow it but to protect those doing it.”

But at least there was the safety of Kirtland Park, and the honor its temporary residents pay one another. “Everyone in South Bend has known me so long that I’m just this weird, crazy guy that talks a lot,” says David Guthrie. “But when I leave South Bend, [I discover] there’s folk like me all around.”