Changing demographics, combined with the three-year effort by state Republicans to suppress minority and youth turnout, led to close races.

Originally published in The American Prospect.

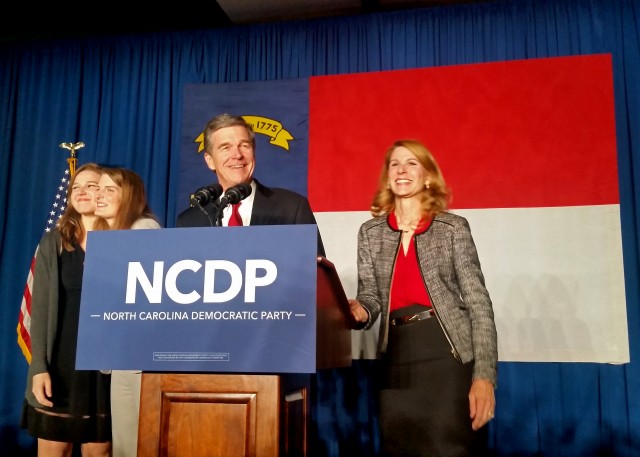

Roy Cooper gives an acceptance speech at the state Democratic Party’s election-watch party. Photo by Barry Yeoman.

BY 12:30 a.m. WEDNESDAY, THE RALEIGH where North Carolina Democrats had earlier been whooping in anticipation of a presidential victory had nearly emptied out. Stragglers were sitting on the floor, eyes fixated on their phones, or yelling back at two large monitors tuned to MSNBC.

Earlier, the network had projected a Donald Trump win in North Carolina, a swing state long considered a key to a Hillary Clinton victory. The down-ticket news was equally disheartening. Deborah Ross, the former state ACLU director, had lost her bid to unseat Republican U.S. Senator Richard Burr. The GOP had seized several statewide posts traditionally held by Democrats, including education chief. And Republicans maintained their supermajority in the state legislature, which over the past few years has restricted voting rights, cut school and safety-net spending, and passed House Bill 2, a broad and costly assault on worker and LGBT rights, best known for its restrictions on transgender bathroom use.

Then a spotlight came on and a disembodied voice announced, “The governor-elect of the state of North Carolina, Attorney General Roy Cooper!” A preliminary tally shows Cooper, the state’s most prominent Democrat, leading incumbent Republican Governor Pat McCrory by 5,000 votes out of almost 4.7 million cast. The official winner won’t be declared until after the county boards of elections count provisional and late-arriving absentee ballots and certify the results during a November 18 canvass. Cooper wasn’t waiting. As the crowd reassembled, he said, “We are confident that these results will be certified and they will confirm victory.”

A wall of cheers went up. “Roy Cooper, I love you,” called out Angela Bridgman, a transgender woman from nearby Wendell, who had lobbied against House Bill 2. Kristin Cooper, the candidate’s wife, dabbed her tears.

It was one of a few celebratory moments for the state’s Democrats, who also elected Josh Stein as the new attorney general (pending the canvass) and flipped the partisan majority on the state Supreme Court. If Cooper’s victory stands, his margin stems in large part from his speaking out against House Bill 2 and refusing to defend it in court.

Both McCrory and the North Carolina Values Coalition, an anti-abortion, anti-LGBT lobbying group, had tried to paint Cooper as an extremist endangering public safety by supporting the right of trans people to use restrooms corresponding to their gender identities. “Even registered sex offenders could follow women or young girls into the bathroom or locker room, and no one could stop them,” said the coalition’s 30-second spot, which showed a man confronting a startled child in a toilet stall.

But North Carolinians were more concerned with the economic dangers posed by House Bill 2: the scuttled corporate expansions by PayPal and Deutsche Bank; the lost convention business; the canceled athletic events and big-ticket concerts; the government travel bans; the empty office buildings. Not only did McCrory embrace the law; so did Buck Newton, the Republican state senator opposing Stein in the attorney-general race.

“House Bill 2 was repudiated by America,” says Floyd McKissick Jr., a state senator from Durham. “When you start to lose on a multitude of levels—jobs, investment, prestige, all the championships—it causes people to understand that North Carolina is on the wrong track.”

OVERLAYING THE CLOSE VOTES in North Carolina was the three-year Republican effort to suppress minority turnout. In 2013, immediately after the Supreme Court’s Shelby County v. Holder decision gutting a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, the emboldened state legislature passed a sweeping law that abolished (or, in some cases, curtailed) a suite of reforms designed to increase ballot access: early voting, same-day registration, youth preregistration, partial ballots for people who arrive at the wrong precincts. The new measure imposed a strict voter-identification requirement that excluded student ID cards. Last July, a federal court blocked much of the law, noting that legislators had passed it “with race data in hand.” The law’s key provisions, wrote the judges, “target African Americans with almost surgical precision.”

What legislators were thwarted from accomplishing, McCrory’s appointees tried to do administratively. Under North Carolina law, the governor appoints county election boards, and all of them have 2-to-1 Republican majorities. In August, state GOP executive director Dallas Woodhouse wrote party activists, asking them for help in cutting early-voting hours. “Call your Republican election board members and remind them that as partisan Republican appointees they have [a] duty to consider Republican points of view,” he wrote. Woodhouse was particularly intent on restricting voting sites on college campuses, and cutting the Sunday hours during which African American churches transport “souls to the polls.”

“Many of our folks are angry and are opposed to Sunday voting for a host of reasons including respect for voter’s religious preferences, protection of our families and allowing the fine election staff a day off,” Woodhouse wrote. “Six days of voting in one week is enough. Period. No group of people are entitled to their own early voting site, including college students.”

Many boards followed suit, and one result was early-voting lines with waits as long as four or five hours. At Duke University, the polls were moved from the center of campus in 2012 to a remote location in 2016. “In 40 heavily black counties, there were 158 fewer early polling places for the all-important first week of voting,” The Nation’s Joan Walsh reported Monday. The same day, the North Carolina GOP boasted that “African American Early Voting is down 8.5% from this time in 2012” while “Caucasian voters early voting is up 22.5%.”

Meanwhile, three county boards went on a wild voter purge that included a 100-year-old African American woman. Before ordering the voters reinstated, U.S. District Judge Loretta Biggs called the purge “insane” and said it felt “like something that was put together in 1901”—just after white supremacists violently crushed North Carolina’s biracial fusion government. “It almost looks like a cattle call,” she told an attorney for Cumberland County, where 5,600 names were removed.

Even on Election Day, when computer failures threw some Durham precincts into disarray, the GOP discouraged state officials from making sure everyone voted. At the historically black N.C. Central University, it took three hours to process just 40 voters. Some waited in line for up to two hours, says law professor Irving Joyner. As the evening grew dark, McKissick, the senator, worked the university cafeteria, making sure that time-squeezed students had not left the line without voting. When Durham election officials petitioned for extended hours, GOP leaders insisted the problems existed in just one precinct. “We have not seen any evidence that would justify extending voting hours for the entirety of Durham County,” party counsel Thomas Stark wrote in a statement. The McCrory administration extended hours in a handful of precincts, though not at N.C. Central University.

IF HILLARY CLINTON’S GROUND GAME wasn’t sufficient to win her North Carolina’s electoral votes, it surely pushed Roy Cooper toward victory (if, indeed, he survives the ballot canvassing). Elected officials and grassroots activists both say the Clinton campaign worked closely with the state party and individual campaigns in an aggressive and targeted get-out-the-vote effort.

Plus, there’s reason to believe that North Carolina is slowly moving in the right direction for Democrats. The current population favors small-town moderates like Cooper; county results suggest he peeled off just enough rural white Trump voters to eke out a win. Ross, the Senate candidate, is more urban and more overtly progressive. But the state is becoming more urban (and diverse), too, which makes candidates like her more credible in future elections. The urban trend also favors Democratic presidential candidates: The counties containing Raleigh, Charlotte, and Durham gave Clinton 57 percent, 62 percent, and 78 percent respectively.

Those demographic shifts remained only theoretical on Tuesday night. Even with Cooper’s and Stein’s apparent wins—and the flipping of the state’s highest court—North Carolina’s failure to deliver Clinton the presidency hung heavy in the Raleigh ballroom.

“Racism won,” Allison Fenderson, a clinical-trials manager from Fuquay-Varina, said of Trump’s election. “No logic. No nothing. He hammered racism from the day he went down that escalator and he never let up.”

“I’m beyond words,” she continued. “I’m starting to drive to damn Canada when I leave here.”