This month marks the 48th anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion, a defining moment in the struggle for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender equality. LGBTQ Americans still face isolation and discrimination. But we in the Baby Boom are also helping redefine what it means to grow older.

Originally published in Medium.

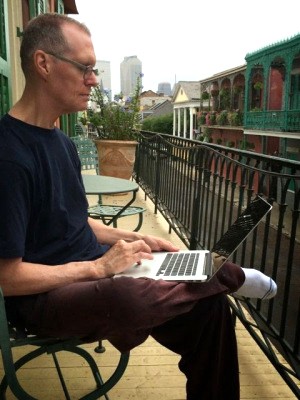

Judith Hoch Wray (left) and Donna Prince have built a good life in Indianapolis, and persevere through financial and medical setbacks. Says Donna: “When I can’t see where the next point of light is, Judith says, ‘It’ll be OK. We’ll just take it a day at a time.’” Photo by Heather.

There are days when I forget I’m gay. I have deadlines to meet, a dog to walk, an appointment with the barber to trim the last of my gray hair. There’s the soup I plan to deliver to some younger friends; they just had a baby and I’m hoping to become an elder in the child’s life. Stepping outside the house I share with my husband, I greet our mail carrier and notice the bamboo is raging out of control again. None of this distinguishes me from my heterosexual neighbors.

It’s a surprising place to find myself after having lived through the most dynamic period in LGBTQ history. We Baby Boomers have one foot in the Stonewall Rebellion — the riots following the June 1969 police raid of a Greenwich Village bar that helped launch the modern-day gay-rights movement — and another in marriage equality. We are the first generation with a wide range of open and successful role models, from out-and-proud entertainers like Ellen DeGeneres to Apple CEO Tim Cook. We can now see our lives refracted back in Coca-Cola commercials and mainstream TV sitcoms. We are also the HIV generation: The virus stampeded through our communities starting in the early 1980s, killing more than 300,000 gay and bisexual men.

“I call this the Gayest Generation,” says Jesus Ramirez-Valles, a professor of community health sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago and author of the 2016 book Queer Aging. “They are the first ones to embrace a gay identity. They were full participants in the gay-rights movement. And then they were the worst hit by the HIV epidemic.”

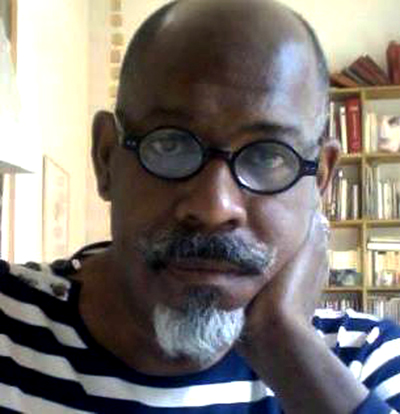

Tony Whitfield, an associate professor at Parsons School of Design, says of gay men, “There’s very little construction of real supporting networks that help us once we age.”

By many measures, the “Gayest Generation” is worse off than our non-queer counterparts. We are less financially prepared for retirement. We have weaker social networks. We face greater health problems, from diabetes to depression. Many of us hesitate to reveal our sexual orientations to doctors, and we worry (with justification) about mistreatment in long-term care. A Harris Poll in 2014 revealed that 32 percent of older LGBTQ people strongly feared “being lonely and growing old alone,” compared to 19 percent of heterosexuals. These disparities are even greater for bisexuals and transgender people.

Indeed, as I traveled around the country between 2014 and 2016, I talked with LGBTQ people, friends and strangers alike, who are socially isolated, emotionally wounded, and financially struggling. Since President Trump took office in January — and stacked his Cabinet with such civil-rights opponents as Attorney General Jeff Sessions and Secretary of Health and Human Services Tom Price — there’s been an additional burden of fear, even among those who are not isolated or otherwise suffering.

That’s not the whole story, though. I also talked with people whose hard lives have made them — made us — more adaptive, more resilient, and better skilled at demanding respect. These are traits that behoove everyone, regardless of sexuality, to develop as we grow older. While there is no single LGBTQ Baby Boomer experience, this much is clear: As the last of us settle into our 50s, and the oldest reach our 70s, we might just have a thing or two to teach our straight friends about aging strong.

Meredith Emmett (left) and Galia Goodman were shaped by the AIDS epidemic. “To have arrived at this age having already lost many people,” Meredith says, “we understand that you rely on your community.” Photo by Eric Waters; taken at Carrack Modern Art’s 2016 Muse Masquerade, Durham, North Carolina.

Some hard memories I never want to shake, because they connect me to people I’ve loved. One of them is sitting in a hospital room in 1989, facing my friend Todd, who was teetering on the edge of consciousness. His lips were cracked and his complexion wan and he had lost his ability to speak. Others were there, too, including his mother and an infectious-disease doctor, all of us trying to discern whether Todd was assenting with a faint nod to having an intravenous medication line removed so he could go home to die.

A few days later, I sat again at his bedside, put on a cassette tape, and quietly narrated the Baroque dance steps we used to do together. I didn’t know if he could hear the music, or hear my permission for him to leave us whenever he was ready. He died shortly thereafter, the day before his 26th birthday.

At his funeral, I wailed without shame. I didn’t expect to be doing this at 29. It felt like a dress rehearsal for aging.

The AIDS crisis, which peaked in the United States in 1995 before new medications made the disease more manageable, was the unifying experience for our generation of gay men and lesbians. It didn’t hit all places equally, but few of us escaped. We watched vibrant lives like Todd’s — he spoke Chinese and Spanish, worked with young immigrants, and was equally graceful on a dance floor and a hiking trail — sputter out unpredictably just as they were taking on definition. We became caretakers, volunteers, and activists. We endured regular blood draws, followed each time by days of bargaining: If I’m still HIV-negative, Lord, I’ll never complain about my hay fever again.

The epidemic blew holes through many gay men’s social circles. Some never fully mended. Gary Marshall, 62, divides his time between San Francisco and New Orleans. He is retired from the federal government, widowed, and HIV-positive. When he was younger, Gary cared for many people as a friend and a volunteer. But now, as he contemplates his own future, he finds his network dwindling.

“In my 30s, when people got sick, there was a lot of us that knew each other and could help change sheets,” he told me. But many have died or drifted away, and the survivors have their own health problems, making him wonder who will care for him. “I’m glad I got to see the best that gay men could be. When the chips were down, at the very worst, we stepped up and supported each other when no one else would. So yea for us. But now, I don’t know how much of that is left.”

Katharine Stewart and Jada Walker at their wedding: “Early on, we wrote health-care powers of attorney,” says Jada, “directly because of what we saw happen every day to people at the mercy of others.” Photo by Cassandra Danielle, FireRose Photography.

But AIDS was also a teacher of lessons, some of which are even more valuable now that we’re older. Jada Walker met her wife Katharine Stewart when they worked at an Alabama HIV clinic. Both witnessed the mistreatment that was common at the time. The couple saw unrecognized spouses barred from ICUs and excluded from life-and-death decisions. They saw transgender women buried in male clothing. After one man died without a will, they say, his parents evicted his partner from their shared home.

“That level of disrespect has informed a lot of what we do,” says Jada, who is 56 and lives a few miles from me in Durham, North Carolina. Both women demand that doctors respect them as individuals and as a couple. They treat diagnoses and treatment plans with skepticism: “I want a second and third opinion on everything,” Jada says. And they’ve been careful to get their documents in order. “Early on, we wrote health-care powers of attorney,” she says, “directly because of what we saw happen every day to people at the mercy of others.”

Others say grieving inspired them to hold more tightly to those who survived. “Maybe because so many of us found ourselves losing friends to AIDS in the ’80s and ’90s, the friends that we have are even more precious,” says Stephen Klein, 67, a retired library administrator living in Long Beach, California.

For me, the memories that most paralleled my own came from a kitchen-table conversation with Meredith Emmett and Galia Goodman. I’ve known the Durham couple for decades — in fact, I recently unearthed a photo from the late 1980s in which Galia and I huddle with a still-healthy Todd at a Gay Pride rally. All of us are smiling and there’s not a gray hair among us.

By the time that photo was taken, we had all buried friends. We had also compiled a mental inventory of one another’s strengths: who could coordinate hospital visits, who could cook meals or soothe parents, who needed to be present for treatment conversations.

“To have arrived at this age having already lost many people, we understand that you rely on your community,” says Meredith, 57, one of whose mentors died of AIDS. In particular, “Galia and I have noticed how quick we are to deal with death and loss — understanding what rituals you create, how you build community, the length of time that the grieving process takes.”

Those lessons have served the couple well during every life transition since. And it reinforced for them the value of creating a network of human connection to sustain them as they age. Meredith consults with nonprofits for a living. Galia, a 66-year-old artist and calligrapher, belongs to our synagogue’s burial society. They’re active in their neighborhood association, and Galia attends an intergenerational belly-dance class. They’ve been trusted adults in the lives of numerous children. “We are not wealthy in finances,” Meredith says. “But we are certainly wealthy in terms of our community.”

Not everyone has so much social wealth, as I saw in one mid-sized town in Indiana. I visited in 2015, the day after the state legislature had started considering the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. The measure, which limited how much state and local governments could “burden a person’s exercise of religion,” was widely perceived as a license to discriminate against LGBTQ people. It sparked a nationwide political conflagration when it passed, triggering boycotts of the Hoosier state, and forcing lawmakers to enact an emergency measure stipulating that the original act didn’t countenance discrimination.

There I talked with a self-employed professional who had previously lived an openly gay life in a large city. But when he moved to the town where his family lives, to be near his aging parents, he also returned to the closet. He knows this isn’t fully rational.

“I guess some of it dates back to when Dad was alive and the possible negative feedback for a minister,” he says. “But he’s been dead going on ten years, and Mom is pretty much home-bound, so it wouldn’t bother her at this point.” He does have a small circle of friends and relatives who either know or it’s understood and unspoken.

“I’ll be the first to admit that I don’t have much of a support system,” he says. He hasn’t dated in over a decade. He lives with his dogs and volunteers with community organizations. He doesn’t share much personal information at the church he attends, even though he knows that most of the parishioners would welcome him as a gay man. “Some months back, they had a couple of guys from a local gay group come and talk to the adult Forum, and I didn’t go. So what does that say?”

Because, almost 40 years ago, I decided that it’s easier to live relatively openly — admittedly, I live in a particularly tolerant community — it’s hard for me to imagine life inside a 21st-century closet. But even today, many of us remain there. (Honestly, there are still moments of hesitation and second-guessing for me, times when saying “my husband” feels like an accomplishment.) A 2010 study by the MetLife Mature Market Institute and American Society on Aging found that only 29 percent of LGBTQ Boomers are fully out. About one-third report being “guarded” with their neighbors, coworkers, and supervisors; 12 percent aren’t open even with even their closest friends.

“It’s not that I’m in the closet,” says Bob Stills, a 67-year-old from Indianapolis who has worked mainly in the food industry. “But I’ve still got one foot in the door. When I was born, gays were still being killed in this country, and nobody cared. When I was nine, my mother came home one day and said that people were whispering about me. She said that before she would see me grow up to be ‘that kind of person,’ she would kill me.” Even though Bob’s mother has since come around, her early rejection — along with similar words from his father and shunning by childhood friends — has led to a life of circumspection. “I’m much more withdrawn and not as open with people as I’d like to be,” he says. He emphasizes that he is still coming out, and that it is a lifelong process.

One 62-year-old from Newark, New Jersey, told me during our interview that almost no one knew he was gay — not his colleagues, not his 12-step sponsor, not the nephew with whom he expects to live when he gets older — for fear that he’d be associated with “drag shows and guys in pink pants.” Later, he did come out to the nephew and the sponsor, with no repercussions. He’s still looking for the right moment to come out at work.

Gallup’s daily tracking poll suggests that, even today, my generation is less comfortable in our skin than the generations that have followed. In 2016, 2.4 percent of Baby Boomers told pollsters they were lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender. That compares to 7.3 percent of millennials born between 1980 and 1998.

In fact, the current political climate under the Trump administration — not to mention some state governments — appears to be nudging some Boomers back toward stealthiness. In 2014 I interviewed a North Carolina lesbian who spoke openly and joyously about her life. As I got ready to publish this article in 2017, I contacted her to update and fact-check her story, and she asked me to remove her from the story. “I am not comfortable being named in the article in this country or this state under the current regimes,” she wrote.

Jesus Ramirez-Valles calls Boomers the Gayest Generation. ““They are the first ones to embrace a gay identity. They were full participants in the gay-rights movement. And then they were the worst hit by the HIV epidemic.”

Researchers say the closet exacts a toll. It shrinks our informal caregiving networks. It makes us less likely to access services like senior meal programs and less likely to report abuse by caretakers. By depriving physicians of important information, it compromises the quality of our medical treatments. “Hiding from wider society the actual nature of one’s sexual identity,” wrote a team of California researchers in one study, has “lifelong and serious consequences.”

Still, it’s never too late to come out, and the benefits accrue immediately. Sande Hines, 69, spent almost three decades as a teacher assistant in New York City schools. That entire time she kept a low profile at work, figuring it was the best way to avoid conflict.

“People would talk about gay people in a negative way, and I had to bite my tongue,” she said. “I used to get along with everybody, and I didn’t want to rock the boat. So I would listen to their stories about their kids and their marriages and their boyfriends. They saw me as someone who smiles a lot and listens.” When she went to clubs on weekends, Sande sometimes saw teachers from work. “It was hush-hush,” she said. “We had something in common but we were not going to discuss it.” The fact that they worked with children only reinforced the code of silence.

Five years ago, Sande decided she was done hiding. “The day of my retirement, I realized I’m free to be myself,” she says. She walked out of school, cut her hair short, and started to speak up about her sexuality. She began frequenting discussions and social events at GRIOT Circle, a Brooklyn non-profit that serves LGBTQ elders of color. “Coming here was like a refreshing breeze,” she says of the organization’s fifth-story headquarters. “These are the best years of my life.”

Like many in my generation, I grew up with images of wealthy gay men with fashionable wardrobes and Fire Island timeshares. While some of those men exist, it turns out that LGBTQ Boomers are behind the curve financially, compared to our heterosexual contemporaries who are also facing retirement.

There are many reasons. Workplace bias kept some of us from rising in our careers. We’ve been excluded from spousal benefits like health insurance. And we’re more likely to live alone and pay others for caregiving. The 2014 Harris Poll revealed that 42 percent of older LGBTQ people seriously fear outliving their money, compared to 25 percent of heterosexuals. The fear is not unfounded: The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs concluded in 2014 that the median retirement account for same-sex couples is 25 percent smaller than that of opposite-sex couples.

Yet adversity has a flipside: Thirty-nine percent of Boomers told the MetLife survey that being LGBTQ made them more self-reliant. Twenty-eight percent said it helped them take more care in financial and legal matters.

I saw both sides of this equation in Judith Hoch Wray, 68, and Donna Prince, 61, who met at New York’s Union Theological Seminary and have spent 26 years together. Early on, Judith was hired to teach New Testament at another seminary, then fired explicitly because of her sexual orientation. She found a patchwork of jobs teaching and working with congregations in crisis, while Donna did pastoral care at hospitals and a nursing home. They invested in real estate, too, but took a hit during the recent housing-market crash. In 2009, with their finances in disarray, they decided to save money by moving 700 miles from New York to Indianapolis, into a two-story brick bungalow they had bought as an investment.

They’ve built a good life in Indiana, centered around strong friendships with members of their church. Even surrounded by loved ones, though, things have been hard. Judith has not worked since an accident left her with a head injury, and she links their financial predicament to the discrimination she faced as a Bible scholar. “If I had been straight, I would be a tenured professor right now,” she says. Donna has been battling breast cancer while also trying to establish a stable income in real-estate research.

What helps them persevere, besides friends and family, is the resourcefulness they’ve built in a sometimes unwelcoming world. “We are not people that live in the box — ” Donna says.

“Any box,” Judith adds, laughing.

“ — and that engages us to look for the next thing,” Donna continues. The couple is always seeking new opportunities, and thinking creatively about work, because nothing has been handed to them.

“If I had been straight, I would be a tenured professor right now,” says Judith Hoch Wray (left), shown here with her wife Donna Prince. Photo by Heather.

Donna is the worrier. She sometimes frets about how they’ll pay next month’s bills. That’s when she leans on her wife’s optimism. “Together, we are so much more stronger than we are apart,” she says. “When I can’t see where the next point of light is, Judith says, “It’ll be OK. We’ll just take it a day at a time.’”

And the source of Judith’s hopefulness? “I think it comes from the deep faith that has been my center from early on,” she says. “I have been carried through this very strange journey by a loving, laughing God. I trust that God — the Universe, however one wants to talk about it — provides. We will have what we need. I’ve proved it true so many times, over and over again.”

When I first came out more than 35 years ago, meeting other gay men was a tricky task. I was fortunate enough to be studying at New York University, in a high-rise dormitory filled with gays and lesbians who had fled Middle America. For many others, though, the safest refuges were discos and bars. They were smoky, youth-oriented, and often hidden away — not exactly geared toward deep conversations or lifetime friendships.

They took their toll, notes Tony Whitfield, a 62-year-old Brooklynite. “When you exist in the kind of male-focused environment that many gay men believed was the world — where building social relationships is profoundly about remaining young and the party — at the point where you’re no longer at the party, many of us find that there’s nothing there,” says Tony, an associate professor at New York’s Parsons School of Design. “There’s very little construction of real supporting networks that help us once we age. Loneliness and isolation are major, major factors for gay men.”

The research agrees that older LGBTQ people tend to be more isolated than our peers. The Harris Poll, commissioned by the non-profit SAGE (Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders), revealed that 40 percent of older LGBTQ people (ages 45 to 75) report shrinking social networks, compared to 27 percent of our straight counterparts. Thirty-four percent live alone, compared to one-fifth of heterosexuals. Other studies have identified sizable minorities of LGBTQ elders who could not name a single person to call in times of need.

Tony, an artist and designer who teaches courses that explore the lives of LGBTQ people and people of color, including a focus on aging, has proceeded differently from other gay men. Identifying himself usually these days as queer (the Q in the acronym), he says, “I get excited by being fed new information that comes with younger people, and because I work at a university, I have that.” He also interacts with young colleagues in the arts world and notes that, in 2017, it’s easier to cast a wide net because young adults are far more comfortable with a fluid understanding of sexuality. “The door’s open to straight men,” he says. “That’s where the change is the most radical.”

Many of the issues faced by gays and lesbians — discrimination, financial stress, social isolation — are magnified for transgender Americans. Not only have they been marginalized in mainstream culture; they’ve also been treated as second-class members of the LGBTQ movement. Even though they’ve been on the front lines for more than a half-century, transgender folks have remained practically invisible to many within our community. I include myself here: When a student of mine recently told me about the 1966 uprising at Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco — a trans-led rebellion that predated Stonewall by three years — I confessed to knowing nothing about it. I was 50 before I knew I had transgender friends.

Here in North Carolina, broad awareness of trans lives came suddenly, with the 2016 passage of the anti-LGBTQ and anti-worker law called House Bill 2. The law’s most notorious provision assigned restroom access in public buildings according to the “biological sex” listed on the user’s birth certificate, forcing many trans women and men into inappropriate bathrooms where they were subject to harassment and even assault. The bill was repealed this year in a devil’s bargain that prevents local governments from protecting their constituents from discrimination.

The fight over House Bill 2 helped call attention to the suffering transgender people have endured as a result of persistent discrimination and invisibility. A 2011 survey of 6,450 transgender and gender-nonconforming Americans found that 41 percent had attempted suicide. (Studies have placed the general-population suicide-attempt rate between 1.9 percent and 4.6 percent.) The study, published by the National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, showed that poverty and job discrimination were rampant among trans people. “The shame, the constant hiding, the fear of discovery just wore me down — to the point where I didn’t want to live anymore,” says Sharon Westfall, a 56-year-old programmer in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, who recently transitioned. Living as a woman was essential to her well-being, she says, but the metamorphosis has been hard. “It took what was a very successful life — married for 31 years, twenty-something years in software development — and threw a grenade in it.”

Yet among the transgender Boomers I interviewed — as with lesbians, gays, and bisexuals — I also saw tremendous resilience. Notably, unlike the population as a whole, older transgender people are less likely to have attempted suicide than their younger counterparts.

Christy Summersett moved to North Carolina ten years ago as part of a work relocation, but was terminated after beginning her gender transition. “Of course, it wasn’t because I came out,” the 60-year-old told me sardonically. “It was for ten thousand other reasons.” The firing spurred her to find a job where she’s respected, as the maintenance manager for a Rocky Mount windshield company. Overall, she says, life on the coastal plain has been good.

“John Doe on the street, that you meet at the grocery, doesn’t care,” she says. “You’re a living, breathing individual. If you’re contributing to society and the economy, fine.” Because she still has a deep voice, contractors sometimes call Summersett “sir” on the phone. “But when I meet them face-to-face,” she says, “they can’t eat their words fast enough.”

Talking with LGBTQ people around the country, I noticed that the happiest ones were those who took concrete steps to make sure they would not be isolated as elders. This often meant living in intergenerational community.

In the early ’80s, when I was at NYU, I had a downstairs neighbor named Linda Villarosa who had just graduated college and moved east to start her journalism career. We lost touch, but in 1991 I saw an Essence magazine article she had co-authored with her mother describing their journey from confrontation back to closeness after Linda disclosed she was a lesbian.

Linda is now 58, living in Brooklyn with her partner and teenage son. (Her daughter’s away at college.) She has built a life of deep connection, and that gives her confidence about the future. “Being a black lesbian” — especially in a stressful city — “you have to find some kind of oasis for yourself through your friendships,” she says. “The world can be hostile to us, so all of us needed to find each other.”

Her model for this was her childhood in Chicago, living with her parents and grandparents and surrounded by elders, including a great-aunt who taught her to read during weekly sleepovers. “We went on vacation together,” she says of her relatives. “My grandmother was really close to her siblings. And I saw the importance of sharing each other’s history [and] talking about each other’s present.”

As an adult, Linda set out to create her own extended family. She is close to her mother and sister, who both now live in New York, and is also deeply connected to her best friend, who lives around the corner. (They are godmothers to each other’s children.) The two households hold big Sunday dinners with their partners and kids, attended by other friends. “That’s been very important as a touchstone, as a weekly ritual,” she says. “It’s like family. It is family to me.” Her children’s father, a gay male friend who also wanted children, remains in their life and joins them on vacations. And her ex remains close and co-parents. Linda was present at her godchildren’s birth and provides care for loved ones after knee replacements and colonoscopies.

“This is a big group of people that I have for the future,” she says. “They’ll be there for me as I get older, and I’ll be there for them. This is something I take seriously.”

Aging for everyone is difficult, and LGBTQ people carry an extra burden. Linda reminds me that, for those of us fortunate and enterprising enough to build and maintain a tight circle of loved ones, it doesn’t need to be quite so scary. “I feel happy,” she says “When I do look in the mirror, I think: Oh! This is a different person than I used to look like. But it’s not bad.”

About this story: Between 2014 and 2016, the author interviewed more than 40 LGBTQ Baby Boomers (and their partners) from eight states, along with leading experts. All interviews were updated in 2017. Much of the initial research was funded by AARP; the research on North Carolina’s House Bill 2 was originally done for the Durham-based Indy Week.

Tip jar: Want to support this work? A contribution of $1, $5, or more will go directly to the author, enabling this type of independent journalism. Go to https://www.paypal.me/BarryYeoman to make a donation of any size.