The fear was that Klansmen would come to replicate the violence that had just racked Charlottesville.

Originally published in The Nation.

LAST FRIDAY MORNING, A REPORT spread through my hometown of Durham, North Carolina, that white supremacists were descending on downtown. “We are carefully monitoring the situation,” said an all-points bulletin to city workers, “and are taking precautions to ensure the safety of employees and visitors.” County offices shut down early. Downtown businesses followed. The sheriff’s office reviewed intelligence and notified community leaders. My synagogue moved most of its Torah scrolls. A City Council member tweeted that the Ku Klux Klan was marching at noon.

Durhamites had reason to believe that our liberal city might be in the crosshairs. Four days earlier, anti-racism activists had hitched a nylon strap to a 1924 statue of a Confederate soldier, then wrenched it off its granite pedestal in front of the old courthouse. In the most immediate sense, the toppling was a reaction to the weekend’s carnage in Charlottesville, Virginia, three hours away. But it was also a manifestation of long-simmering tensions in Durham, where unequal treatment of African Americans by the criminal-justice system has been well documented, and where a spruced-up downtown, featured in foodie magazines, has driven up real-estate costs and displaced blacks and Latinos from nearby neighborhoods.

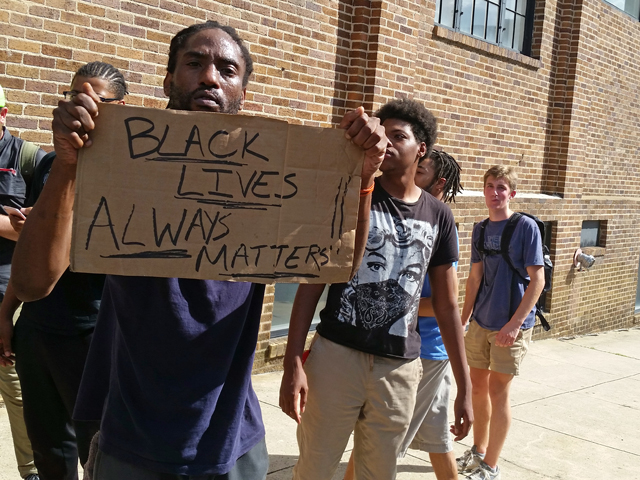

The fear on Friday morning was that Klansmen would come to protest the destruction of the rebel statue and replicate the violence that had just racked Charlottesville. In response, as 12 o’clock approached, hundreds of local residents migrated downtown. They assembled near the old courthouse: millennial and Boomer, mainstream and revolutionary (one carrying a rifle), racially diverse, and determined to hold the supremacists at bay.

“There’s a certain veil that’s being uncovered,” said shirlette ammons, a 43-year-old Durham musician who came downtown that morning. “We think explicit racism has disappeared, but it’s resurfacing in a way that makes it impossible not to be part of the resistance.”

For some, the emboldened white-nationalist movement has been clarifying but familiar. “It’s the visual image of what we’ve faced our whole life,” said Zainab Baloch, a Muslim-American state employee, who drove 30 minutes from Raleigh, where she is running for City Council. Baloch, the daughter of immigrants from Pakistan, was in fifth grade during the September 11 attacks. After that, she told me, “we were forced to defend ourselves every day, even as children. We had to be nice. We had to show kindness. But obviously, after this election, that method is not working.”

Noon arrived with no sign of the Klan. The loose assemblage lined up in parade formation. They carried drums and banners and an eight-foot-tall puppet of Martin Luther King Jr. “This is what community looks like,” they chanted as they marched through the downtown streets.

FOR THE REST OF THE AFTERNOON, the activists took peaceful control of the block in front of the old courthouse. News estimates ranged from “hundreds” to about 3,000 people. Confronting the Klan is serious business here: the state’s political history is laced with white-supremacist terror, including the 1898 coup d’état that overthrew a biracial government in the coastal city of Wilmington. During the 1960s, as North Carolina’s leaders were trying to steer a moderate course on civil rights, the KKK claimed 10,000 members statewide, more than the rest of the South combined. Then, in 1979, Klansmen in Greensboro, North Carolina, murdered five Communist Workers Party activists in broad daylight and with TV cameras rolling. The assailants were acquitted by two all-white juries.

The Durham protesters waited throughout the afternoon for the Klan to arrive. Instead, they encountered a dribble of aggrieved white men.

The 40-year-old in the blue tank top, with the knife hanging from his belt and the Iron Cross tattoo on his bicep, insisted he didn’t come downtown looking for trouble. “I was waiting on a ride,” he said. But when the man (who called himself a Durham native and a debt collector) saw the anti-racism signs and the bare granite pedestal, he couldn’t keep his mouth shut. “Slavery is an African idea,” he argued, not something that whites like himself should be blamed for. And yes, he said, he supported equal rights, but “it’s not equal anymore. The damn white man’s being discriminated against now.”

With those resentments, he and a friend blundered into the crowd. They were quickly enveloped by protesters. One woman raised a black-power fist. He responded with a Nazi salute. (“I was trying to tell her the sign she threw was a hate sign too.”) Before the conflict could escalate, the two men slipped away from the old courthouse and were escorted onto a side street by City Council member Charlie Reece and other volunteers. They vented for a while, then disappeared.

The occupation took on the air of a celebration. Bottled water and snacks arrived by the case. Volunteer marshals in orange vests kept the peace. A percussion band showed up and turned part of the block into a dance party. Poets free-styled and organizers led chants.

At 3:30, police ordered the road open to traffic again. Some protesters, fueled in part by a rumor that the Klan might still show up, stayed in position and prepared to get arrested.

“I’m holding ground,” said Melody Ashe, a 37-year-old Pilates instructor. “I believe the KKK should not be granted access to this area. I don’t want to want to hear a single vile word.” She held part of a long black banner that said, “We will not be intimidated.”

Ashe was not arrested; nor was anyone else at the moment. (Later, during a smaller march, one anti-Klan protester would be arrested for failing to disperse.) Police tried to reopen the road by relocating their cruiser, which had been serving as a traffic barrier. A protester angled his own car into the same position. The occupation continued.

By late afternoon, it was pretty clear the Klan wasn’t showing. What’s more, District Attorney Roger Echols had just promised to consider the mayhem in Charlottesville, and the country’s history of racial injustice when prosecuting the eight activists arrested on felony charges for toppling the statue. “Asking people to be patient,” he said at a news conference, “and to let various government institutions address injustice, is sometimes asking more than those who have been historically ignored, marginalized, or harmed by a system can bear.”

Echols said he’d also weigh the effect of a 2015 state law that bars local officials from permanently moving historic monuments. It was enacted by Republican legislators after filmmaker Bree Newsome took down the Confederate battle flag in front of South Carolina’s statehouse. As a result, the DA said, “Durham citizens have no proper recourse.”

Unbeknownst to the activists, across town, Duke University President Vincent Price was about to authorize the removal of a vandalized statue of Robert E. Lee from the facade of the campus’ neo-Gothic chapel. It would be gone by sunrise.

As the afternoon wound down, Eva Panjwani, an organizer with the Workers World Party Durham, which was involved in the toppling of the statue, raised a bullhorn and urged people to disperse. “Stay safe,” she said as the block started clearing. “Go back to your community and tell them stories of our victory. We sent them home.”