“Packing” and “cracking” voters boosted the GOP and muted urban voices. Now federal judges have struck down the latest redistricting plan.

Originally published in CityLab.

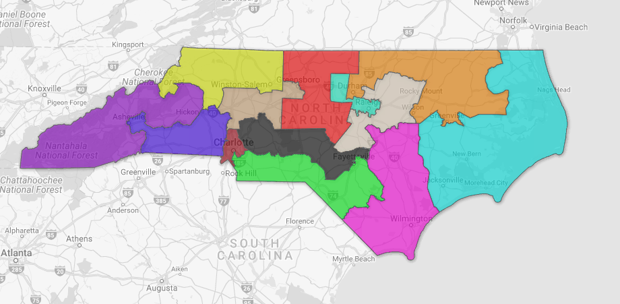

Congressional district lines in North Carolina managed to limit the representation of urban voters. Image courtesy of State Board of Elections.

WHEN NORTH CAROLINA’S LEGISLATIVE LEADERS WERE ORDERED to redraw the state’s 13 congressional districts in 2016, they gave their hired mapmaker an explicit instruction: Maximize the Republican Party’s electoral advantage.

North Carolina is a purple state, closely divided in its support of the two major parties. State Representive David Lewis, senior chair of the House Select Committee on Redistricting, nonetheless wanted to see more red on the congressional map. “I acknowledge freely that this would be a political gerrymander, which is not against the law,” he said at a committee meeting. “I propose that we draw the maps to give a partisan advantage to 10 Republicans and 3 Democrats because I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and 2 Democrats.”

The mapmaker, Thomas Hofeller, knew how to achieve this: by stripping electoral power from North Carolina’s cities.

There are two key ways to gerrymander: “packing” and “cracking.” Packing a district means cramming it with like-minded voters—more than are needed to guarantee a safe seat. Cracking a community means spreading its voters across multiple districts in which they hold the minority view. Put the two strategies together, and “the cumulative effect is that it dilutes voices, including urban ones,” says Tomas Lopez, executive director of the nonprofit advocacy group Democracy North Carolina.

That’s what Hofeller did in five North Carolina cities, according to a ruling issued Tuesday by a three-judge federal panel that struck down North Carolina’s congressional districts. Voters in Raleigh and Durham were packed into Democrat David Price’s 4th District, while Charlotte residents were concentrated into Democrat Alma Adams’ 12th District. That made it easier for the surrounding districts to stay Republican. Meanwhile, Democratic-leaning Greensboro and Asheville were each split between two Republican districts.

“There are a lot of ways to neutralize urban voters, and this is one of them,” says Democratic state senator Terry Van Duyn. She comes from Asheville, a mountain city that is countercultural, outdoorsy, and assertive about its progressive values. “My vote just doesn’t count,” she says of U.S. House races. “And because they cut Asheville in half, we contribute to the fact that our congressional delegation is not representative of our state.”

Tuesday’s decision, written by 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge James A. Wynn Jr., was the first time the federal bench declared a congressional map unconstitutional based on partisan gerrymandering. Courts have often thrown out maps because of racial bias—indeed, it was a race-based federal-court ruling that forced North Carolina’s 2016 congressional redrawing. (That decision was affirmed by the Supreme Court in May.) But courts have been more permissive of electoral districts drawn solely to benefit political parties.

Wynn’s opinion, which could be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, breaks new legal ground. Out of 24,518 possible maps generated by Duke University mathematician Jonathan Mattingly, the judge noted, more than 99 percent gave Republicans fewer than the 10 House seats they currently hold in North Carolina. This “reflects an intentional effort to subordinate the interests of non-Republican voters,” he wrote.

“Partisan gerrymandering runs contrary to numerous fundamental democratic principles and individual rights enshrined in the Constitution,” he continued. “Long-standing, and even widespread, historical practice does not immunize governmental action from constitutional scrutiny.”

NORTH CAROLINA’S LEGISLATURE HAS NEVER BEEN KIND to cities. Back in the 1990s, when it was controlled by Democrats, a National Rifle Association lobbyist courted legislators with seafood parties and Christmas gifts and convinced them to invalidate local gun-control ordinances, which cities like Durham favored.

When Republicans took control of the legislature in 2011, they went into preemption overdrive. In 2016, after Charlotte passed an ordinance protecting LGBTQ residents, lawmakers famously passed House Bill 2, which forced transgender people to use restrooms corresponding to their birth certificates in public buildings. The law, which has been partially but not fully repealed, also barred cities from enacting certain labor standards and civil-rights protections.

More surgically, the legislature went after individual cities. When Durham City Council refused to annex land in a watershed to accommodate a developer, the legislature extended the municipal boundaries by fiat.

Redistricting lines neatly divided liberal Asheville’s voting base. Image courtesy of State Board of Elections.

Not surprisingly, none of the current legislative leadership comes from a major metropolitan area. Republican leaders often cast North Carolina’s cities as outsiders to the political mainstream, which they define as conservative and rural. Former Governor Pat McCrory, a Republican, invoked “North Carolina values” to justify both House Bill 2 and another law banning sanctuary cities. And at a hearing last August—called to get public input on state legislative district maps—state GOP executive director Dallas Woodhouse suggested that Donald Trump’s sweep of white rural North Carolina should signal the state’s political direction. Trump won 50.5 percent of the vote in North Carolina but lost the seven most populous counties, all of them urban.

“It is not the job of this committee to make a political party that lost 76 [of 100] North Carolina counties in the presidential election competitive, because they are uncompetitive in vast swaths, vast areas, of the state,” Woodhouse said. “The minority party in this body has a geographic problem.”

No one has suggested that North Carolina’s congressional map was drawn with the overt purpose of harming cities. But both gerrymandering and preemption suggest a willingness on the part of legislative leaders to diminish cities’ power in the service of their electoral and policy goals.

Ultimately, the question of partisan gerrymandering will be settled by the Supreme Court, which heard a Wisconsin case in October and more recently agreed to hear a Maryland case. The North Carolina case could land there too. (The legislative defendants have already requested a stay.) If the high court agrees with Wynn, and declares extreme partisan gerrymandering off-limits, it will become considerably harder to justify ignoring cities at redistricting time.