Louisiana’s Interstate 10 corridor between New Orleans and Lafayette has been described as the “most musical 125 miles on Earth.” It is famously the birthplace of jazz, zydeco, and Cajun music, and also has its own brand of funk and R&B. But New Orleans and South Louisiana also have a strong blues tradition, which exists below the radar yet provides the DNA for much of the Pelican State’s other music.

Still Singing the Blues is a two-part, two-hour radio documentary series released in 2010. It features musicians in New Orleans and South Louisiana who continue to perform both traditional blues and more commercial rhythm-and-blues. Part 1, also called “Still Singing the Blues,” burrows into the lives of three outstanding older performers: Carol Fran of Lafayette, Harvey Knox of Baton Rouge, and Little Freddie King of New Orleans. Part 2, called “Crescent City Blues,” takes listeners into the New Orleans neighborhood joints that keep the blues and R&B alive.

The programs played on more than 200 public and community radio stations across the country. They are now available for downloading and listening online for free.

Below: Listen to Still Singing the Blues (download here)

Below: Listen to Crescent City Blues (download here)

Meet the musicians

Here are some of our favorite audio clips that we could not use in the finished documentary.

Carol Fran, a vocalist and pianist, grew up in a Creole family in Lafayette with relatives who spoke both French and English. She performed blues and R&B for more than 70 years, wowing crowds with her expressive voice and sassy audience rapport. During her marriage to blues guitarist Clarence Hollimon, who died in 2000, the duo toured Europe regularly and played at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. Last year she sang at a festival in São Paulo, Brazil. She died in 2021. In this two-minute clip, Fran tells about the time Elvis bought her lunch.

Carol Fran, a vocalist and pianist, grew up in a Creole family in Lafayette with relatives who spoke both French and English. She performed blues and R&B for more than 70 years, wowing crowds with her expressive voice and sassy audience rapport. During her marriage to blues guitarist Clarence Hollimon, who died in 2000, the duo toured Europe regularly and played at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. Last year she sang at a festival in São Paulo, Brazil. She died in 2021. In this two-minute clip, Fran tells about the time Elvis bought her lunch.

Harvey Knox came from Talullah, a North Louisiana town that had a thriving Delta blues scene. He moved to Baton Rouge during its blues heyday and performed with such greats as Slim Harpo (“I’m a King Bee”). Knox often played his guitar until dawn at the rural juke joints that rose out of the cane fields of West Baton Rouge Parish. Later in his life, he performed at Baton Rouge’s Club Infiniti and at a local nursing home, supplementing his income by repairing televisions and other electronics. He died in 2019. In this short audio clip, Knox tells why his grandfather made him get a job racking pool.

Harvey Knox came from Talullah, a North Louisiana town that had a thriving Delta blues scene. He moved to Baton Rouge during its blues heyday and performed with such greats as Slim Harpo (“I’m a King Bee”). Knox often played his guitar until dawn at the rural juke joints that rose out of the cane fields of West Baton Rouge Parish. Later in his life, he performed at Baton Rouge’s Club Infiniti and at a local nursing home, supplementing his income by repairing televisions and other electronics. He died in 2019. In this short audio clip, Knox tells why his grandfather made him get a job racking pool.

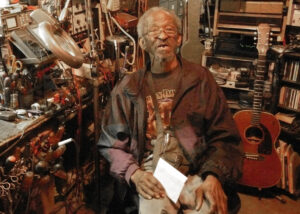

Little Freddie King hopped a freight train when he was a teenager and rode from McComb, Mississippi to New Orleans. He taught himself guitar and began playing at such rough bars as the Busy Bee, which he memorialized in his song “Bucket of Blood.” King plays and sings a “gutbucket” blues that incorporates hints of New Orleans jazz and brass-band music but never loses its raw edge. His music reflects his hard life, which has included a successful battle with alcohol abuse. In the following audio clip, King gives a detailed description of building his first guitar from almost nothing.

Little Freddie King hopped a freight train when he was a teenager and rode from McComb, Mississippi to New Orleans. He taught himself guitar and began playing at such rough bars as the Busy Bee, which he memorialized in his song “Bucket of Blood.” King plays and sings a “gutbucket” blues that incorporates hints of New Orleans jazz and brass-band music but never loses its raw edge. His music reflects his hard life, which has included a successful battle with alcohol abuse. In the following audio clip, King gives a detailed description of building his first guitar from almost nothing.

Larry Garner, a military veteran from Baton Rouge, worked for much of his life as a preventive-maintenance specialist for Dow Chemical. He started playing blues professionally at Tabby’s Blues Box in the 1980s, and touring internationally after his early retirement in the ’90s. He has traveled through Tunisia, Russia, and Switzerland, and like many American roots musicians, discovered there are often more enthusiastic audiences abroad than at home. Here he talks about the close connection between the blues and gospel, and about his showdown with a local deacon.

Larry Garner, a military veteran from Baton Rouge, worked for much of his life as a preventive-maintenance specialist for Dow Chemical. He started playing blues professionally at Tabby’s Blues Box in the 1980s, and touring internationally after his early retirement in the ’90s. He has traveled through Tunisia, Russia, and Switzerland, and like many American roots musicians, discovered there are often more enthusiastic audiences abroad than at home. Here he talks about the close connection between the blues and gospel, and about his showdown with a local deacon.

John T. Lewis, a guitarist and vocalist, was one of twelve children in a musical family in the Lower Ninth Ward. He was a drum major in his high-school marching band. After a stint in the Army, he came home and developed a love affair with New Orleans’ distinctive style of 1950s R&B. “It overtook my soul,” he says of the music. Lewis worked as an appliance repairman until he finally took the risk of becoming a musician full-time. In this audio clip, he talks about the record trucks that used to drive through his childhood neighborhood.

John T. Lewis, a guitarist and vocalist, was one of twelve children in a musical family in the Lower Ninth Ward. He was a drum major in his high-school marching band. After a stint in the Army, he came home and developed a love affair with New Orleans’ distinctive style of 1950s R&B. “It overtook my soul,” he says of the music. Lewis worked as an appliance repairman until he finally took the risk of becoming a musician full-time. In this audio clip, he talks about the record trucks that used to drive through his childhood neighborhood.

C.P. Love spent his childhood both on New Orleans’ West Bank and among sugar-cane cutters on a plantation in Vacherie, Louisiana. From early on, he developed a soulful vocal style inspired both by legendary singer Sam Cooke and by the African, Caribbean, and Latin rhythms of New Orleans rhythm-and-blues. R&B was grounded in life’s hardships, he says, and “musicians keep themselves out of a lot of trouble by letting it out by singing.” Here he talks about performing in Port Sulphur, south of New Orleans, during segregation. His story reminds us that Black musicians have had to contend with ugly racism, even from their own patrons.

C.P. Love spent his childhood both on New Orleans’ West Bank and among sugar-cane cutters on a plantation in Vacherie, Louisiana. From early on, he developed a soulful vocal style inspired both by legendary singer Sam Cooke and by the African, Caribbean, and Latin rhythms of New Orleans rhythm-and-blues. R&B was grounded in life’s hardships, he says, and “musicians keep themselves out of a lot of trouble by letting it out by singing.” Here he talks about performing in Port Sulphur, south of New Orleans, during segregation. His story reminds us that Black musicians have had to contend with ugly racism, even from their own patrons.

Credits

Still Singing the Blues was produced and written by Richard Ziglar and Barry Yeoman.

Project director Richard Ziglar is an audio documentarian whose credits include Oprah Winfrey’s Harpo Productions; AARP’s Prime Time Radio; American Public Media’s “The Story”; and the North Carolina Arts Council.

Reporter Barry Yeoman, a former Louisianan, is a freelance journalist who teaches at Duke University and Wake Forest University.

We are indebted to Ben Sandmel, Karen Leathem and Michael Hurtt, who, through their contributions as humanities consultants, enriched our experience and made this project larger and more generous than we could have imagined.

Thanks to the staff at two radio stations, KRVS and WRKF, who showed enormous confidence in our ability to produce a broadcast-worthy documentary.

Still Singing the Blues is sponsored by Filmmakers Collaborative, a non-profit support organization for independent media makers. The documentary is financed, in part, by a generous grant from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

We appreciate everyone who helped match our grant from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. We are particularly grateful to these major donors: Anonymous, in honor of Bethany Bultman; Keith A. Caruso, M.D., PLC; Tom Colton and Ellen Simms; Rebecca Skloot; Steven Stichter; Vaguely Reminiscent, Durham, N.C.; and the Yeoman Family in Merrick, N.Y.

We appreciate Guitar Joe Daniels of Joe’s House of Blues and O.D. Raiford of Young at Heart Club, both in New Orleans, for opening up their clubs to us (both have since closed), along with the Keith Lewis Blues Revue, which played regularly at Young at Heart during our research period. Other clubs where we recorded include The Place to Be, B.J.’s Lounge, Margaritaville, and d.b.a. (all in New Orleans) and Club Infiniti in Baton Rouge.

Special thanks to everyone who assisted with the production of this documentary: David Alvarez, Barry Ancelet, Julia Botero, the late Andy Cornett, Jamie Dell’Apa, Kat Dobson, Tim Duffy, Deb Fleming, Stephen Fowlkes, David Gordon, Jordan Hirsch, Ivan Klisanin, David Kunian, Walker Lasiter, Rachel McCarthy, Judith Meriwether, Jerry Moran, Rachel Nederveld, Ike Padnos, Johnny Palazzotto, Liz Rhine, Michael Sartisky, David Spizale, Dave Tilley, Wacko Wade Wright, the late Rich Wilson, and Randall Williams. Most of all, thanks to the musicians and others whom we interviewed for this documentary, often for hours at a stretch.