For all its combativeness, the Republican National Convention failed the address the country’s most fundamental issues. Scenes from a week in St. Paul.

Originally published in Indy Week.

Army Spc. Benjamin Thompson, twisted his arm toward the cameras. “This means ‘God hopes for peace,'” he said. Then he began sobbing. Photos by Barry Yeoman.

THE VETERANS MARCHED IN LOCKSTEP as they approached the Minneapolis State Capitol, which sits on a hill overlooking downtown St. Paul. Some wore Army greens. Others wore camouflage or pressed black T-shirts. “It’s all right, it’s OK,” they chanted in a call-and-response. “Remember MLK/ tried to lead the way/ but he was shot one day/ in the early morning.” They turned a corner, climbed the domed building’s wide stairs, and for a few moments stood silently at attention.

It was 10 a.m. on Labor Day. In a few hours, the Republican National Convention would convene at the Xcel Energy Center a mile away. Here on the Capitol grounds, anti-war activists were gearing up for a demonstration that would draw some 10,000 people. There would be anarchists and puppeteers, grandparents and students. None would possess the discipline, or the dignity, of these 60 members of Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW).

Earlier that morning, IVAW had marched to the Xcel Center. There, they say, police agreed to escort 1st Sgt. Wes Davey, a 28-year Army veteran, inside the perimeter with a letter addressed to Sen. John McCain. The letter asked the GOP presidential nominee to support better treatment for returning warriors, especially those with brain injuries and post-traumatic stress. Once Davey was inside, though, no one from McCain’s campaign would speak with him or even accept the document.

“We would have taken just about any staff member,” said Sgt. Matthis Chiroux, a former Army photojournalist who served in Afghanistan but refused deployment to Iraq after his honorable discharge. “They weren’t willing to send the lowliest intern out to meet with combat veterans.” This was a stark contrast, Chiroux said, to the Democratic National Convention in Denver, where Sen. Barack Obama’s campaign agreed to work with IVAW on improving veterans’ care.

On the Capitol steps, Army Spc. Benjamin Thompson, a young man with a ruddy face and a buzz cut, rolled up his T-shirt sleeve to reveal an Arabic tattoo. “I made a promise to someone who drew this for me,” he said. “Can you take a picture?” The artist, he said, was “one of my prisoners at Abu Ghraib, a place where you saw all those photographs. But you didn’t know the half of it.” He twisted his arm toward the cameras. “This means ‘God hopes for peace,'” he said. Then he began sobbing.

“We had 10-year-old boys in my camp,” he finally continued. “We had an 80-year-old blind man.” Thompson was panting as he spoke, trying to hold back tears. “They were killed by enemy fire because we did not protect them when they were in our custody.” Not only that: “We were giving them food that made them sick. We were giving them water that gave them kidney stones. They were dying from lack of heart medication that they had been on for 20 years.”

Next to Thompson stood Marine Cpl. James Gilligan, who in 2004 made a compass-reading error that led to a fatal assault on an Afghani village. Today he held the photo of a fellow Marine killed in action. “It’s a fucking shame that young men and women like this have to die for a lie,” he said.

I asked Gilligan where he was from.

“I’m right now living in Philadelphia,” the lanky Marine said. “I just came off of being homeless for the past two years.”

“How are you doing?”

“I had a suicide attempt in 2007. I’ve been to at least seven VA hospitals. I’m not finding help. I’m not finding any kind of solace.”

Cathedral of St. Paul

A brother and sister held a banner with pictures of Obama’s face on one side and a dismembered fetus on the other. “A Vote for Obama is a Vote for Dead Children!” it said. Next to them stood a man in a pinstriped suit and glasses. His sign said, “COULD WE VOTE 4 HEROD?” It referred to the Roman king who, according to the book of Matthew, ordered the mass slaughter of Bethlehem’s male babies.

Randall Terry in St. Paul. He has urged abortion-rights foes to “let a wave of hatred wash over you.”

The man in the suit was Randall Terry, a former pothead who later discovered Jesus and founded the anti-abortion group Operation Rescue. (The group has since disavowed him.) In the 1980s and ’90s, Terry and his followers blockaded abortion clinics, trapped patients in their cars and screamed at them as they walked into clinic buildings. At the 1992 Democratic National Convention, Terry arranged to surprise President Clinton with a dead fetus. The following year, he urged supporters to “let a wave of hatred wash over you.” He has been arrested numerous times, most recently at last month’s Democratic convention.

Now, on the cathedral sidewalk, Terry was demanding that Catholic bishops condemn Obama and his running mate, Sen. Joe Biden, for supporting abortion rights. “Bishops wear red for a reason — it’s the stuff martyrs are made of,” he said. “And if they are going to have apostolic continuity, they need apostolic courage to declare that we cannot participate in this Holocaust with our vote.” He announced a series of sit-ins, “where people are arrested,” later this month at Obama headquarters in swing states (including, possibly, North Carolina).

Who is Terry voting for? I asked.

“I’m leaning toward McCain” — instead of a third-party candidate — “because of his appointment, frankly, of Gov. [Sarah] Palin.” Naming the Alaskan as his running mate, Terry said, was “genius.”

As he was talking, Cathy Smith and her sister Judy Wolf walked by, wearing powder-blue T-shirts and buttons with pictures of doves. The Southern Minnesotans were in town for Peaceful Presence, an interfaith vigil for delegates, their families and others working at the Republican convention. The women looked at the graphic banner, then turned to reprimand Terry. “Jesus was non-violent in his approach to things,” said Smith. “This is a very offensive way to express Christianity.”

“Are you Catholic?” Terry asked.

“I am,” Smith said.

“Then you need to uphold the teachings of the Catholic church.”

“I need to hold up the teachings of Jesus,” Smith responded. “His were non-violent.”

Terry was growing impatient. “Ma’am,” he said, “you’re so open-minded that your brains have leaked out.” He walked away, then returned to shout at the sisters. “Jesus condemned Judas to hell. That’s an act of violence. Jesus said: If you cause a little child to stumble, you’d be better off having a millstone tied around your neck and be drowned in the sea. That’s an act of violence.”

“Those were the words somebody used to describe what they thought he was saying,” Smith responded.

Terry threw his head back and laughed. “Just so you folks understand,” he told us, “this lady is a perfect illustration of how Catholic bishops have failed in their duty. For her to stand here and to say things that are heretical, silly, foolish and otherwise stupid in the name of Catholicism shows the bishops haven’t done their job.”

“I don’t believe in abortion,” Smith said.

“It’s not that you don’t believe in it,” Terry said. “It’s that you sit there with this pompous pomposity.”

“If you want people to listen to you, don’t tell them they have pompous attitudes. Because your words to describe your views will turn people off, like me.”

“Listen,” Terry said. “If I’d have said it calmly and quietly, you wouldn’t have heard me. Because you’re in transmit-only.”

“Thank you,” the sisters said. They waved and walked away.

Xcel Energy Center

While Terry was relegated to the streets of St. Paul, more law-abiding figures of the American Right roamed the halls of the Republican National Convention. They were thrilled about the nominations of McCain and Palin.

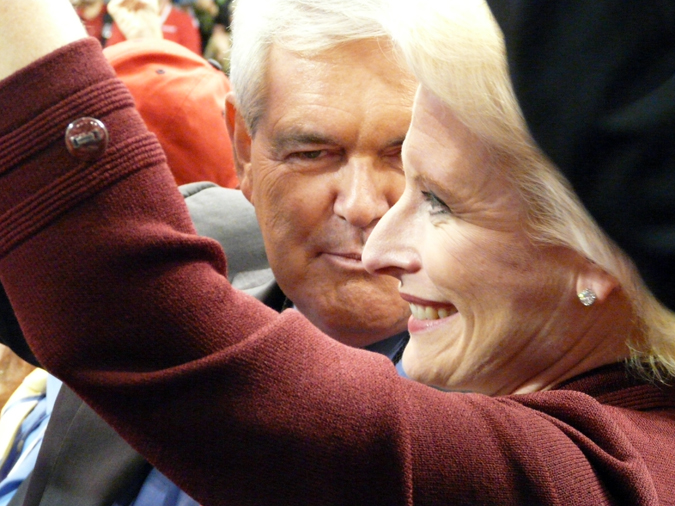

One night, I found myself almost pressed against former House Speaker Newt Gingrich. While delegates danced to “Go, Johnny, Go,” Gingrich called 2008 a “turning point” for his party. “Frankly, the Republicans deserved the defeat of 2006,” he said. “They spent too much. They didn’t do oversight. They failed at Katrina.” Gingrich insisted that McCain and Palin represent “a remarkable shift toward a Theodore Roosevelt reform Republicanism.”

Gingrich cut off the interview before I could ask him how Roosevelt, a conservationist, might have felt about drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, or the shooting of wolves from airplanes, two measures Palin supports as governor. Or whether Roosevelt would have endorsed Gingrich’s forthcoming book, Drill Here, Drill Now, Pay Less.

Outside in the hallway, Gary Bauer, a “pro-family” activist who ran for president in 2000, scurried from one interview to the next. Bauer heads American Values, a group that blames the nation’s problems on its “secularization.” He helped write the GOP platform, which he bragged is “more conservative than Sen. McCain is,” especially on stem-cell research, immigration and the environment.

Bauer told me he feels comfortable with McCain, “even though there’ll be times I might get irritated with him.” He’s more excited about Palin, particularly in the light of her daughter’s pregnancy. “Kids make mistakes,” he said. “Often the most important point for a family is when that mistake is made. How does that family react?” By making it clear to Bristol “that they loved their soon-to-be-born grandchild,” Bauer said, the Palins “sent a tremendous message to the rest of America about the sanctity of life.” (So much for keeping Palin’s children off-limits.)

Back on the convention floor, 84-year-old Phyllis Schlafly stopped to talk with her North Carolina admirers. The Washington Times has called Schlafly “arguably the most important woman in American political history”: As founder of the Eagle Forum in the 1970s, she was one of the first modern activists to mobilize conservative Christians. She led the crusade against the Equal Rights Amendment, which she still claims was a “radical feminist” smokescreen for gay marriages and tax-funded abortions. She staunchly opposed arms treaties. Today, the Eagle Forum says it wants to secure the U.S. borders against “illegal aliens… Third World diseases, criminal gangs, and potential terrorists.”

In St. Paul, Schlafly hosted an anti-abortion party where, in front of 800 guests, she deftly tore up the sign of a protester who tried to disrupt the event. Palin was supposed to attend but canceled at the last moment, leading Schlafly to tell ABC News, “This is clearly somebody in the McCain campaign who doesn’t understand where the votes are coming from.”

Still, she told me, “I’m very encouraged about this ticket. I think we will be able to turn the country around. I am very distressed with a lot of the ways things are going in this country” — she mentioned our high divorce rate, porous borders, and lack of energy independence — “but I’m hopeful that the conservatives are getting their act together.”

I asked Schlafly if she was distressed by how our society was moving on the abortion issue. No, she said: “The country is getting incrementally pro-life.”

“How do you feel about the increasing number of states that are offering civil unions, or in some cases marriage, to same-sex couples?” I asked.

“Well, I think that’s a bad move, and I hope we can stop it,” said Schlafly, who has a gay son. “And the people are in favor of stopping it.”

“I have to go now,” Schlafly said. She was quickly escorted away.

Target Center, Minneapolis

Featured prominently at the Republican convention were most of the candidates McCain defeated in the primary. Notably absent was the last man standing: Ron Paul, the libertarian Texas congressman who assembled a loyal, Internet-savvy following. Paul opposes the war in Iraq (and the war on drugs) and wants us to withdraw from the United Nations and NATO. He favors making guns easier to buy and clamping down on illegal immigration. He’d abolish the IRS, Department of Education and Federal Reserve.

The Republicans didn’t want him in St. Paul. Never mind: He and 10,000 supporters held their own shindig across the river.

The sidewalk outside Minneapolis’ Target Center looked a bit like a hippie be-in that had been crashed by friendly survivalists. A young woman with knee-length red dreadlocks waved a campaign sign as wide as she was tall. She rolled back her eyeballs and sang “The Star-Spangled Banner,” with the words rewritten as an anti-government rant. An unemployed man from Missouri (“my job is to defend the Constitution”) milled around with a cigarette and a can of Pabst. His black T-shirt said, “Don’t Tread on Me.” He chatted with a GOP delegate from Massachusetts, who sported a ponytail and talked about “how big of a fraud” the IRS and Federal Reserve are.

Inside the sports complex, thousands cheered as Paul, in a video, walked through a gun shop, greeting the customers’ children. Then they gave a warm ovation to Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform and longtime associate of disgraced Republican lobbyists Jack Abramoff and Ralph Reed.

“Let me summarize: taxes bad, guns good,” Norquist started, before laying into big-government liberals. “We do not ask for gun stamps. We do not go knocking on people’s doors telling them that they should become hunters. We do not insist that every fourth-grade child in America be assigned books in public schools entitled Heather Has Two Hunters.” The audience whooped and snickered, and Norquist went on to describe the “various coercive utopias” of the Democratic Party: “The environmentalists who have made the toilets too small to flush completely, who made the cars too small to put entire families into. Their little to-do list for the rest of us is a little longer and more tedious than Leviticus.”

A few minutes later the crowd heard from John McManus, president of the right-wing John Birch Society. “The Constitution requires the federal government to protect the states from invasion,” he said. “Isn’t 20 million illegal immigrants an invasion?” When the cheers died down, McManus posed the question, “Why don’t they close the borders?”

“They suck!” someone called out.

Momentum was building toward the hottest speaker of the afternoon: former Minnesota governor Jesse Ventura. The retired pro wrestler wore a gray jacket over a yellow Navy Seal T-shirt. Long gray hair fell from his balding head. Ventura threw some meat to the conspiracy theorists in the room. (“Why has the United States not charged Osama bin Laden for 9/11?” Audience: “He didn’t do it!”) He defied the party line by coming out against the border fence (“We’re going to turn my country into East Berlin!” Ideologically inconsistent audience: “Boo!”) And he went to the mat for the Second Amendment.

“I’m not a gun-totin’ fool,” Ventura preached. (We are! the audience responded.) “But I get so pissed off when I hear them say, ‘We’re not going to take away your ability to hunt.’ (Boo!) Ladies and gentlemen, I got news for you: When our forefathers wrote the Constitution with the right to bear arms, it was not about hunting. (That’s right!) The second amendment is there so that we the public, if our government is out of control, we have the ability…. ”

By this point, the chants of “Jesse!” had grown so thick that no one could have possibly heard the end of the former governor’s sentence.

Holiday Inn Minneapolis Metrodome

Sitting aboard a bus that would take them to a midnight party, North Carolina’s Republican delegates were stoked. Two hours earlier, accepting the vice presidential nomination, Alaska Gov. Palin had charismatically filleted Obama.

“When the cloud of rhetoric has passed, when the roar of the crowd fades away, when the stadium lights go out, and those Styrofoam Greek columns are hauled back to some studio lot — when that happens, what exactly is our opponent’s plan?” Palin asked to repeated applause. “What does he actually seek to accomplish after he’s done turning back the waters and healing the planet? The answer is to make government bigger, and take more of your money, and give you more orders from Washington, and to reduce the strength of America in a dangerous world.”

“She was just awesome,” said Barbara Swann, the wife of a delegate from Hampstead, N.C. “She reminds me of Sally Fields in Norma Rae.”

“I’m on fire,” said delegate Larry Lambeth of Asheboro, N.C.

Now it was time to celebrate. On tap was a reception for the North Carolina, South Carolina and Alabama delegations, sponsored by the German carmaker Daimler. It would be held on the 50th floor of a downtown Minneapolis skyscraper.

As the bus idled outside the delegates’ hotel, Chris McClure, executive director of the N.C. Republican Party, came aboard with a warning: The bus in front of us had been stopped by demonstrators. Ours will get a police escort, he promised, but still “we could get caught off guard.”

“Our radiant beauty will deflect all the protesters,” said Kelly Holdway, an alternate delegate from Raleigh.

“Shall I run them over?” the driver asked.

“Yeah,” Holdway said. “Please do.”

For the next 10 minutes, a patrol car, blue lights flashing, zigged and zagged alongside us, blocking the one-way cross-traffic at every intersection for almost three miles. We ignored red lights, barreling unimpeded thanks to the Minneapolis P.D.

At Windows on Minnesota, delegates ordered free drinks and grazed on a selection of upscale foods with a vaguely Southern theme: pulled-pork sandwiches, buffalo burgers, bacon-wrapped shrimp skewers. A country-music band was taking a break, and Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama” blared through the speakers. I made my way around the party taking notes — and as soon as Daimler PR manager Jessica Altschul spotted me, she cut across the room to introduce herself. I asked her the reason for the party. “Although we are a German company, we have a strong continued presence in the United States,” she told me. (Daimler makes trucks and buses in North Carolina.) “We wanted to make sure people still knew that.” Altschul said the company was not lobbying for any state legislation.

I turned to delegate Vernon Robinson, a former Winston-Salem alderman. “Do you find [these parties] a little unseemly?” I asked.

“Somebody said that if you can’t drink their liquor and take their money and vote against them, then you shouldn’t be in this business,” Robinson said. “There might be some naïve individual out here, but I understand that Daimler is pushing an agenda, and it’s probably an economic-subsidy agenda. Should I ever grace the halls of public office again, I will be voting against subsidies as vociferously as I was the first eight years I was in public office.

“Yes, I take their drink, eat their food, and then vote against them.”

Inside the Xcel Energy Center

The most revealing 10 seconds of the actual Republican convention came during Rudolph Giuliani’s speech. The former New York mayor had just laid out McCain’s biography, and then turned to contrast it to Obama’s. “On the other hand, you have a résumé from a gifted man with an Ivy League education,” Giuliani began. “He worked as a community organizer — ”

Then he paused. The delegates howled with amusement. Giuliani, obviously pleased with himself, chortled too.

You could picture how a film director might portray this moment: The camera would pan slowly from white face to white face, each one contorted in derisive laughter. The notion that someone would start his career at the neighborhood level, helping the poor and unemployed improve their living conditions, and from there build the credentials for the presidency, seemed to them incomprehensible. The laughter morphed into a chant of “Zero! Zero!” with thumbs and forefingers curved into circles.

Delegate Jeanne Smoot, a former Reagan administration official from Raleigh (center): “I think many of the community organizers are very good and hardworking and decent people.”

This was the tone of the rest of the week. Once Hurricane Gustav had passed — and with it the rhetoric of there-are-no-Republicans-or-Democrats-during-a-natural-disaster — the convention took on a meanness absent during the Democrats’ gathering. One could not have imagined, for example, Democratic delegates turning toward the press and booing for 25 seconds, as their GOP counterparts did during Palin’s speech.

In Denver, the Democrats paid frequent tribute to the torture McCain endured as a war prisoner in Vietnam. “The personal courage and heroism John demonstrated still amaze me,” said Biden. “But I profoundly disagree with the direction that John wants to take the country.” By contrast, the Republicans relentlessly mocked Obama’s history working with unemployed steelworkers and low-income tenants.

“We were speaking facts,” said GOP delegate Vinnie DeBenedetto, a town council member from the Raleigh suburb of Holly Springs. “Being a community organizer doesn’t mean that you have a responsible leadership kind of job.” Was laughing at Obama appropriate? “I think the laughter is part of the frivolity of a convention,” he told me.

Thursday night, I asked Linda Daves, chair of the N.C. Republican Party, whether the laughter and booing were “over the top.”

“No,” she said.

“Why?” I asked.

“I think that the expression here is genuine, and it’s sort of a matter of freedom of speech. Kind of like the freedom of press.” She flashed me a tight smile.

“The bottom line is: How many conventions have you been to?” she asked.

“Twelve,” I estimated. (Later, I counted. It was 10.)

“OK. You know people are very expressive about expressing their opinions at these things.”

“This has felt different, even from a lot of Republican conventions I’ve been to,” I told her. “It’s felt a little more ‘red meat’ to me, I guess.”

“Well, it hasn’t felt that way to me,” Daves said. “I think you’re probably just digging for a story that’s not there.”

It did feel that way to other delegates. Jeanne Smoot, a former Reagan administration official who lives in Raleigh, found the laughter during Giuliani’s speech disquieting. “I didn’t like that, personally,” she said. “I think many of the community organizers are very good and hardworking and decent people.” As for the booing of reporters, “I didn’t think it was very smart. The media, after all, is the fifth estate. It keeps us honest.”

By then, McCain was preparing to speak. A burly man wearing an earpiece warned the North Carolina delegates, “Be ready for hecklers. The counter-chant is ‘USA! USA!'” (One of the infiltrators was IVAW’s Adam Kokesh, a former Marine protesting McCain’s record on veterans’ issues.) McCain touchingly recounted his biography and managed to get in a few mistruths about Obama. (He opposes nuclear power! He’ll raise your taxes! His health-care plan will reduce your wages!) Compared to the feverish oratory of the night before, though, it felt low-key and lecture-like. The nominee had been one-upped by his vice-presidential pick.

When McCain finished, confetti fell, followed by balloons, many of which popped as soon as they reached the ground. Heart’s 1970s hit “Barracuda” blasted through the Xcel Center. Heart guitarist and singer Nancy Wilson, no fan of the McCain-Palin ticket, would later tell an Entertainment Weekly reporter, “I feel completely fucked over.”

For me, though, there couldn’t have been a more fitting ending to the week.